The Wizard of Os

The story of the legendary Osei Kofi, nicknamed The Wizard Dribbler, who may just be the most accomplished Ghanaian footballer of all time. As written by Fiifi Anaman

The late Thomas Freeman Yeboah was a prominent and prolific Ghanaian football historian and statistician. He was one of the very best the country has ever produced.

In November 2020, he wrote a controversial article about the greatest footballer Ghana has ever produced.

After acknowledging the greats — the likes of “CK Gyamfi, Aggrey Fynn, Baba Yara, Osei Kofi, Ibrahim Sunday, Mohammed Polo, Abdul Razak, Abedi Pele, Asamoah Gyan etc” — he settled on two exceptional players, based on “thematic areas such as individual brilliance, team work, titles, individual awards and consistency.”

“After a careful study and review of Ghanaian football history, I could say Ghana’s all-time best player is a straight battle between Abedi Pele and Osei Kofi,” Freeman declared.

Right.

Osei “The Wizard Dribbler” Kofi versus Abedi “The Maestro” Pele.

Interesting.

Even more interesting is that I am reading this article out loud to Osei Kofi, who is on the verge of turning 84, and who — getting to hear of the article for the first time — is listening with rapt attention.

We are in his home in Kasoa, many miles away from Accra, and we’re seated face to face.

He is nodding and smiling as I’m getting to the part where Freeman made his choice.

“However…” Freeman wrote. “…undoubtedly, Osei Kofi has contributed more to the success story of Ghanaian football than The Maestro…”

“Ahah,” Kofi shouts. “There it is! That’s it! The key thing here is ‘success story of Ghanaian football’!”

He laughs.

“If you are talking about achievements for Ghana, I mean, Ghana, it’s not a contest. But I often don’t like to talk about it because it’s not as if anybody will give me a prize for it!”

“But on a more serious note,” he adds. “The greatest of all-time debate is always difficult. People make all sorts of arguments. I believe it is easier doing it generation by generation. And when it comes to my generation, nobody came close. Nobody played better than I did.”

The legendary Baba Yara, whose name adorns Ghana’s biggest stadium in Kumasi, is considered by many of the footballers from Ghana’s golden era to be the greatest ever, yet Freeman argued: “Baba Yara was very talented, but his football career suffered a major setback when he had to retire during his peak because of an accident which paralyzed him, so in terms of achievements, he comes nowhere close to Osei Kofi and Abedi Pele.”

“Baba Yara was a great man,” Kofi says. “I learnt a lot from him. He had the complete format as a footballer.”

Osei Kofi, now a pastor widely referred to as Reverend Osei Kofi, is a very opinionated man.

And he is allowed to be, because having been involved with football since the 1950s, his opinion on matters in the sport carries the weight of his experience.

In the article, Freeman, who passed away in February 2021, wrote that compared to Osei Kofi, Abedi Pele fell short of winning laurels within the larger Ghanaian context.

Abedi Pele may have won the 1982 Afcon with Ghana, but he was just a 17-year-old member of the squad who didn’t make a significant contribution, Freeman argued.

He may have won the 1993 UEFA Champions League — and finished as a finalist the year before — but that was for Olympique Marseille, a club in Europe, Freeman further argued.

Indeed, respected Ghanaian historian Anokye Frimpong, earlier this year, made a point. He said Abedi Pele is often considered Ghana’s greatest player because he played in Europe. According to Frimpong, there were exceptional players like Osei Kofi, who ruled the roost “long before African football was known to the Europeans.”

“It is only when you go to Europe that you make a name and are seen in the world,” he told GTV’s Kafui Dey in an interview. “When you talk to people of yesteryears, they will tell you that they came across better players,” he added, going on to say that Pele does not come anywhere near Osei Kofi.

Meanwhile, Osei Kofi, Freeman wrote, was “the face” of the Ghana team that won the Afcon in 1965, where he was tournament MVP and top scorer with three goals.

What Freeman hadn’t added was that Kofi was also one of Ghana’s best players, if not the best, when the country reached the final of the 1968 Afcon in Ethiopia, losing 1–0 to Zaire (Congo) in Addis Ababa. Kofi scored four times en route to the final.

“With all due respect to Abedi Pele,” Osei Kofi laughs. “He didn’t do anything for Ghana!”

Well, of course Osei Kofi doesn’t literally mean “anything”, but you get the point.

Kofi continues: “Last year (2023), I heard FIFA celebrated me with an honorable mention. They said that it was impressive I achieved everything I did as an amateur…”

[The era of amateurism saw footballers in Ghana not paid as players, rather having mainstream jobs while playing football on the side]

“… I never played professional football. But Abedi had the chance.”

Osei Kofi — once described by the Daily Graphic as “easily Ghana’s most accomplished player” — could have played professional football too.

In 1969, after his club, Ghanaian giants Asante Kotoko, had had a two-week tour of the UK, Stoke City offered him a 30,000 pound contract to sign for them.

Kotoko had lost the Stoke game 3–2 on July 25, with Kofi brilliantly bagging a brace in a man-of-the-match performance. According Kotoko official A. Appiah Menka, Kofi earned the nickname “George Best of Ghana” after the game.

English goalkeeper Gordon Banks — the 1966 World Cup winner widely considered to be the globe’s best goalkeeper at the time — recommended to Stoke to sign on Kofi. “Banks held my hand after the game and took me to the officials,” Kofi recalls. “He said, ‘Sign him up! In about two years, this man would be a better player than George Best’”

Banks had been a long-time admirer of Kofi. The latter had scored a gorgeous goal against the former when Stoke City visited Ghana a year earlier, in March 1968, in a match Kotoko won 3–1.

But the contract — which would have seen Kofi bag a colossal 10,000 pounds, with Kotoko earning the rest — never materialized.

“Kofi turns down big offer,” the Daily Graphic reported.

“I didn’t turn it down o,” Kofi laughs. “I didn’t even know they had offered me the contract until we touched down back in Accra. I learnt about it at the airport when our team manager, Dogo Moro, told me.”

Kofi was summoned to a meeting to discuss the contract. At the meeting were the Asantehene, owner and life patron of Kotoko; Mr BM Kufour, a director of the club; and Mr BK Edusei, a big bankroller of the club.

“They said, ‘Osei, this is the contract that is before you. Are you going to leave us too?’” Kofi recalls.

“Too”, because Wilberforce Mfum, captain of Kotoko, had left the club for the US to play professionally in 1968, weakening the team.

Kofi says he felt bad about betraying the club he loved, a club he had been playing for since 1962.

“Imagine these three big men asking me to stay?” he says. “I couldn’t say no.”

Abedi Pele, who was captain for Ghana and tournament MVP at the 1992 Afcon in Senegal, where Ghana finished with silver medals, won the Africa Footballer of the Year award three times. But, as Freeman argued, Osei Kofi could have easily achieved same and even more had the award — established in 1970 — existed in his prime.

“In 1965, Osei Kofi was widely rated as the best footballer on the African continent, so as in 1966 and 1967,” Freeman wrote. “When the award was first instituted in 1970, he was named 7th best player in Africa.”

Kofi should “curse his stars”, according to Freeman, because he could have “easily” won the 1970 award, had it not been for his infamous refusal to play for Ghana at the 1970 Afcon in Sudan, where the Black Stars finished second after narrowly losing the final 1–0 to the hosts.

Many believe the Black Stars would have won that tournament had Kofi — that year described by the Daily Graphic as “one of the best soccer stars on the continent” — travelled to Sudan.

So, why did he refuse to go to the Afcon?

Apparently, at the time, some players of the national team complained that because they were spending a lot of time in camp, they were missing out on salary increments at their work place.

Most of the players worked in various capacities at the Sports Council. The players approached Kofi to speak on their behalf to the authorities.

And he did, except it didn’t end well.

“I told Mr LTK Caeser (Deputy Director of Sports) about the fact that the players needed pay increases at work to motivate them,” Kofi says.

“He retorted, ‘Are you a graduate?!’

“I felt very insulted,” Kofi complains. “I insulted him back!”

What did you say?

“I said, ‘Wonni***ase!’” [Suck your mum]

Whoa.

“I said, ‘Have you ever seen a graduate play for the Black Stars? Because of you, I won’t go to Sudan!’ And I packed my things and left the camp for Kumasi.”

His teammates later went to Caeser to apologize on Kofi’s behalf. “Osei is like that, go easy on him,” they pleaded.

Indeed, he was like that.

Kofi was known to be very outspoken; a troublesome firebrand. He tells me that that is why he never captained the Black Stars, even when it got to his turn to. “I wasn’t disciplined,” he states, plainly.

One fateful day in November 1965, hours before the Black Stars left Accra for Tunis to play at the Afcon, Kofi led a mutiny in the Black Stars team.

This was after finding out that Ohene Djan, the famous and powerful Director of Sports, had helped players of Real Republikans within the team to get 20 pounds each from the Bank of Ghana before travelling.

Real Republikans, known as OOC (Osagyefo’s Own Club) had been formed in 1961 by Djan, on the instructions of Osagyefo Dr Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president, to serve as Ghana’s super club.

Kofi says this favoritism towards OOC players was an unfair treatment towards the players from the other clubs. Thus he led a group of four others — Kwame Nti, Ben Kusi, Agyemang Gyau and Barnieh — within the team to leave the Black Stars camp at the Accra Sports Stadium.

“I wasn’t the captain, but I commanded things in the team as if I were,” Kofi says.

[Kofi’s injured Kotoko teammate Wilberforce Mfum was the substantive Black Stars captain then, but Republikans’ Charles Addo Odametey captained the team in his absence]

“Ohene Djan walked barefoot after us to the stadium gate to settle the issue, but we didn’t budge,” Kofi says.

When the players got to the traffic light about four hundred meters from the stadium, where Ghana’s Gender and Social Affairs ministry is now located — “it used to be the American Embassy in those days” — Kofi and co met BK Edusei, the influential Kotoko benefactor, in his car.

“Where are you going with your things,” he asked them.

“We didn’t want to complicate things and tell him the truth,” Kofi says. “So we told him we were travelling to Tunisia and wanted somewhere to place some of our things till we come back.”

“You can keep your stuff in my house,” BK Edusei said. “I’ll take you there myself.”

“Not knowing Ohene Djan, who was a close friend of his, had already told him about the issue,” Kofi reveals.

“When we got to Edusei’s house, Ohene Djan was somehow already there!” he continues.

“Apparently, as he was following us to the traffic light, he saw us with Edusei and quickly anticipated that he would take us to his house, so he quickly went back to the stadium for his car and sped away to Ringway Estate, where Edusei’s house was located.”

After a tense meeting, Edusei led an amicable resolution of the matter, settling the players 20 pounds each. “He was a very rich building contractor,” Kofi says of Edusei.

“Ohene Djan then drove all of us in his brand-new Benz car back to the camp at the stadium,” he grins. “It was around 6pm, and just three hours later, we flew to Tunisia.”

It was good that Osei Kofi eventually went to Tunisia, because he ended up putting up one of the most memorable Afcon one-man shows ever, helping Ghana defend the title they first won in 1963 on home soil.

Ohene Djan named the 1965 Afcon “Osei Kofi’s Cup”, and after the final, which Ghana won 3–2 against the hosts in Tunis, gave Kofi a piggy ride.

That wasn’t the only thing Djan did for Kofi.

On the team’s way to Tunis, at a duty-free shop in Rome, Kofi saw a gramophone and jokingly asked Djan to buy it for him.

“He told me if I performed in Tunisia he would do so on our way back,” Kofi remembers.

During the final, when Ghana was losing 2–1, Kofi heard someone clap out loudly to him from the stands.

It was Ohene Djan.

“I went to the touchline and he gestured with his hands, as if to say, ‘Don’t you want the gramophone anymore?’ I raised my hands and said, ‘Oh Director, I understand’.”

A few minutes later, goalkeeper John Naawu kicked the ball long to Kofi.

“I had seen the Tunisian keeper relaxing at the edge of their box,” he remembers, “and so after a few touches, I lifted the ball and volleyed it from a long distance.”

It was some hit, as with the aid of the tail wind, the ball flew into the net for the equalizer.

In extra time, Kofi was at it again, curling a corner kick that almost entered the net. The ball bounced off the bar and fell to Frank Odoi, who headed it in for the winner.

So influential was Kofi at the 1965 Afcon that Ken Bediako, the veteran sportswriter, coined the nickname “One-man Symphony Orchestra” for him.

It was a great year for Kofi. Before the tournament, he had scored three goals as Ghana beat archrivals Nigeria 7–0 over two legs to win the 1965 Azikiwe Cup.

He capped that year by being officially crowned with the prestigious Ghana “Sportsman of the Year” award.

Osei Kofi had first been invited into the Black Stars team as a 19-year-old in 1961.

Well, he was actually 21, because many years later, his illiterate mother would discover that his official date of birth, June 3, 1942, had been a mistake: it was actually June 3, 1940.

Kofi was born and bred in Koforidua, and his talent for football shone right from infancy. As a wondrous winger, he played football in school, as well as at colts (grassroots) level, later getting to play for Koforidua Corners, which was the junior team of Koforidua Kotoko.

He moved to Tema, in the Greater Accra Region, after completing school in 1958.

That year, he recalls one of his uncles sending him to Ghana’s first FA Cup (then known as Aspro Cup) final at the Accra Sports Stadium.

It was a match between archrivals Hearts of Oak and Asante Kotoko, Ghana’s biggest and most successful clubs. “It was on a Sunday,” he remembers with a smile. “And by Saturday night I was already dressed and ready to go! I will never forget that match. Kotoko won 4–2.”

That match was memorable for Kofi not only because it inspired his dream of one day playing for either side, but also for the way legendary sportswriter Kofi Badu of the Daily Graphic described the game. Sixty-six years later, Kofi is still able to recite the lengthy opening paragraph of the match report word for word.

Seriously, you should hear him do it.

In Tema, Kofi worked as a driver’s mate to his father, a former footballer, who drove a truck that transported dynamites to and from Ghana’s Western Region to blow up rocks used to build the Tema Harbour.

“There was a field behind our house in Tema where workers from the various companies played football,” Kofi explains. “For about three months, I tried and failed to get selected to play any of the matches. I was discouraged and almost quit football.”

One day, however, while watching a game, one of the players got injured. The referee signaled to him.

“Small boy, get in!”

He was indeed small. He was 18, and stood at 5 ft 4. But everyone on the field that day were about to discover a diminutive dribbler.

Kofi had not expected the breakthrough, and so he had gone to the game without boots. He recalls entering the game barefooted, which was common at the time.

After daringly dribbling the older, bigger footballers and striking a first shot, the referee, amazed, stopped the game and asked him to go home and bring his boots.

“The match was stopped as I rushed home to put on boots,” he says. “After the game, workers from as many as six companies approached me and offered me a job. I eventually ended up at Tema Development Corporation (TDC), and learned to become a draftsman.”

At TDC, Kofi worked under an expatriate called Mr Moody, who one day discovered Kofi playing football in the Tema neighborhood. “Kofi!” he called out. “I never knew you could play football!”

Moody happened to be the coach of Accra Great Argonauts, which was a club in Division 2, the second tier of the Ghana league system. He drafted Kofi into his team.

In the 1960/61 season, Argonauts failed to qualify for the Ghana Premier League, but this didn’t hurt the fortunes of Kofi, whose displays meant he was discovered by Hearts of Oak.

Before his first game at Hearts, Kofi recalls a costly mistake: eating a heavy bowl of fufu for lunch, hours to the game.

“I felt so heavy and dizzy during the game,” he laughs. “And I totally flopped! And it was the traditional Ga derby between Hearts and Great Olympics too, so you can imagine. I will never forget the kind of insults I received during and after the match.”

Kofi says he packed his belongings and ran away to Koforidua, ashamed and disappointed. He was later visited by his older, more experienced teammate, the celebrated playmaker Amadu “Tear Away” Akuse, who convinced him to come back.

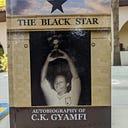

In his next game, “I avoided the fufu!” he says, and put up an excellent performance against Real Republikans, resulting in Ohene Djan and national assistant coach CK Gyamfi inviting him into the Black Stars.

Due to the presence of way older, more experienced players, Kofi would find playing opportunities in the Black Stars to be few and far between from 1961 to 1964.

“There were seniors within the team who had been playing since the 50s,” he says. “I was then young and upcoming and needed to bid my time. I remember even having to wash their jerseys and polish their shoes. They were manly players who commanded a lot of respect. I had to serve.”

During this time, though, he got a rare, priceless opportunity of playing in the Black Stars’ famous 3–3 draw against global giants Real Madrid at the Accra Sports Stadium. It was in August 1962.

“I don’t think the Black Stars had trained that hard for any match in its history,” he recalls. “Ohene Djan called us to a meeting weeks before the game and told us that if we conceded less than 10 goals, there would be a party thrown for us!”

Real Madrid, the world’s most powerful club, were then five-time European champions, and had the best players in the world, the likes of Ferenc Puskas, Alfredo Di Stefano and Francisco Gento, who all came to Accra.

Kofi was a second half substitute. “I remember jogging unto the pitch, excited and nervous, and immediately feeling a heavy knock to my head. It was striker Edward Acquah. You know him? A goal machine. They called him “the man with the Sputnik shot’. ‘Don’t come in and play to the gallery!’ he warned me. I said, ‘Oh, can’t I dribble just a little bit?’” Kofi remembers, with stifled laughter.

As it turned out, Kofi sent in the cross that led to Acquah heading home his second of the game, making the score 3–2. “During the goal celebration, I said to him, ‘Can I dribble now?!’ and he laughed.”

Kofi’s next big opportunity for the Black Stars would come in a one-all drawn game against Argentina at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. “Regular right winger Kwame Adarkwa had a fever, and coach CK Gyamfi approached me and asked if I could fill in. I was like, “this is why I was brought here! Of course I can and I will.”

“After the game, CK walked up to me and said, ‘Osei, you have really surprised me’. CK told me that though I was handicapped in height, I had exceptional brains as a player.”

Kofi would go on to play at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, and the 1972 edition in Munich, becoming the first and (so far) only Ghanaian footballer to play at three Olympic Games.

Kofi, and some other young footballers from Ghana’s New Horizons team, had been sent to Tokyo ‘64 to understudy the senior players and gain experience.

Indeed, Kofi had been on standby for quite a while, without whining, waiting for his chance at shining.

At the Afcon in December 1963, he had been a 21-year-old standby member of the team, and didn’t get to feature at the tournament.

In January 1964, Ohene Djan had formed the New Horizons, a national team B, made up of youngsters being groomed to replace the ageing Black Stars players, and made Kofi captain.

It was in 1965 when coach CK Gyamfi, who had become Ghana’s first black coach in 1962, thrust Kofi into the team proper, propelling him to international superstardom.

From then onwards, he became the poster boy of the team.

“After Ghana ‘63 and Tunisia ‘65, we could have won it three times on the bounce at Ethiopia ‘68, but we had qualified for the Olympics and so everyone was focused on that,” Kofi reflects. “No one wanted to get injured and miss Mexico City, and so we admittedly didn’t give our all.”

Ghana finished runners-up in Ethiopia in January 1968.

It was at Hearts of Oak that Kofi burst onto the Ghanaian football scene as a talented teenager. He helped the Phobians win the 1961/62 league, emerging as a standout performer, earning the nickname “Little Wonder Boy”.

But he would leave soon, in a controversial transfer to Kotoko.

In those days, as it is now, it was a taboo for a player to switch clubs between Kotoko and Hearts, considering the level of enmity between them.

But it happened, and in a bizarre, dramatic way too.

“The story’s interesting,” Kofi begins. “My father had a wife, and I didn’t like the way she maltreated him. My father decided to divorce her, and the court asked him to pay 30 pounds as settlement. He didn’t have that kind of money, and so he went to his boss, BK Edusei, for the money.

“I’d never known that Edusei was the owner of that truck we’d been driving all along. Edusei, obviously a Kotoko man, was told by someone that his driver’s son was Osei Kofi. So what did he do next? Your guess is as good as mine. He told my father that he would give him the money on condition that ‘your son joins Asante Kotoko’.”

And so Kofi was in camp with the Rainbow Club in March 1962, jubilating after winning the league, when his father visited and told him about the development.

“That very night, I snuck out of Hearts’ fold and left for Kumasi, joining Kotoko,” he says.

Kotoko ended up being Kofi’s home for the next 14 years, where he would win six league titles and play in four Africa Cup finals — 1967, 1970, 1971 and 1973 — winning one (1970).

It could have been three, too, but for infamous controversies in the 1967 and 1971 finals.

In the 1967 finals, Kotoko failed to turn up for a third leg against TP Englebert (now TP Mazembe) on December 27 after both initial legs in November ended in draws (1–1 in Kumasi, and 2–2 in Kinshasa).

In that second leg in Kinshasa, there was a 2–2 draw even after extra time, and as was the trying tradition then, there was to be a coin toss to determine the winner.

A French translator who travelled with the Kotoko team informed them that he had overhead the Congolese officials planning a sinister strategy. Even before the coined dropped, they would lift up their captain to signify they’ve won, in order confuse the whole process and cheat their way to the title.

Kotoko’s officials informed the match commissioner. The game was abandoned, with a third leg planned for Douala in Cameroon.

“Unfortunately, we were absent during the third leg because officials of the Ghana Football Association failed to inform us of it,” Kofi, who was top scorer at that tournament with two goals, explains.

In the 1971 finals, Kotoko defeated Canon Yaounde 3–0 in Kumasi, and lost the second leg 2–0 in Yaounde, thereby clearly winning over the two legs.

But a strange technicality — that said points, and not goals, were suddenly the determinant of the winner — meant a third leg had to be played just days later.

Canon won the third game 1–0.

“Can you believe it?” Kofi says.

Osei Kofi initially almost regretted joining Kotoko, known as the Porcupine Warriors.

“Brother, there is something in football,” Kofi says, seriously.

Pardon?

“I mean, there is a lot of juju (voodoo); a lot of supernatural and superstitious machinations and manipulations. Anyone who tells you otherwise is a liar.”

Kofi says that for eight months after leaving Hearts, he couldn’t properly play for Kotoko. “Anytime I saw a football I would mellow and become very afraid,” he recalls. “It was beyond the physical.”

“Kotoko took me to a fetish priestess called Afia Asaah, a very beautiful woman outside of Kumasi, to spiritually diagnose the cause of my inability to play.

“I stayed with her and was regularly given concoctions to bath. I was eventually given a talisman to wear around my waist for three days to fortify me.

“My brother, it was serious. Football will really take you places. I remember for about 30 minutes after wearing that thing, you could cut me with a knife and I wouldn’t feel it.”

Mmm?

“I was also given an alcoholic concoction to drink for three weeks,” he continues, “and it was so powerful I remember I would sleep with constant erections.”

“Eventually, the fetish priestess told me the cause of my inability to play in a parable. She said, ‘Osei, you belonged to a band where you were a leading trumpeter. The leader of that band is the cause of your woes. He has worked on you spiritually’.

“The team manager of Kotoko, who was then with me, mentioned the name of the President of Hearts of Oak then — you and I both know who he was so I won’t mention his name — saying ‘Is he the one?’. The fetish priestess simply said, ‘Yes. And because of the name you have mentioned, Osei will play football again.”

Kofi did indeed play football again, and boy did he succeed in style. “I remember tormenting Hearts anytime we met,” he laughs.

“They used to call me ‘Osei bɛte’ (Osei will redeem), because of my knack for scoring equalizers.”

“I’ll tell you what,” he continues. “Kotoko is a very spiritual club and playing for them comes with its own perks and problems. I remember in a particular match we played, I scored four goals, and when I was asked by the press how I managed to, my mind blacked out. I could not remember how I scored those goals. Heck, I could not remember that I had even scored those goals! It was as if I had been possessed.”

At Kotoko, just as at Hearts, Kofi says he experienced an entrenched tradition of juju.

“There was this one time: my teammate Robert Mensah and I were directed by the most powerful patron of our club to see a linguist for rituals. This was because the team was not performing well and a remedy was being sought.

“We were made to swallow cowries among other scary and serious rituals. Afterwards, the linguist said to me, ‘Because of what you have, one of you will die soon.’ I don’t think Robert heard him, but I did, and I was scared.”

The eccentric Robert Mensah, considered to be the greatest Ghanaian goalkeeper of all time, died on November 2, 1971 under strange circumstances. Named runner-up for the African footballer of the year award that year, he was infamously stabbed by a friend at a drinking pub in Tema.

“That was the prophecy fulfilled right there,” Kofi claims. “I knew Robert died because of Kotoko.”

There was another time, in the middle of 1970, when Kofi suffered an injury. “I had never been injured that intensely before,” he says. “It was unusual.”

It was so serious that it pushed him, through a friend’s recommendation, to seek answers from a fetish priest in Mampong, Ashanti Region.

“The priest was called Kofi Nti, and he lived with Dwarves.”

Wait a minute: actual Dwarves?

“Yes, actual Dwarves,” Kofi says. “I interacted with them while I lived with the priest.”

“The first time I saw one, his coming was preceded by lightning. I don’t know where he came from, but he sat in front of me and mentioned my name. I was shocked that he could even talk, much less speak Twi. Apparently, they can speak every language.

“He called out, ‘Osei! What brings you here?’ I told him I had come to seek answers to my injury, and he asked, ‘What did you bring?’”

Kofi pulled out a bottle of Schnapp and threw it to the Dwarf.

“He grabbed it with his left hand, opened it, and gulped down everything at a go. I kid you not. After throwing away the bottle, he asked, ‘Do you now believe there are mysteries in this world?’

“I said, ‘If I didn’t believe I wouldn’t be here.’”

The Dwarves, Kofi claims, offered to take him back to their habitat in the mountains for 40 days, in order to fortify him spiritually. He told them he would think about it.

Much later, Kofi recovered from his injury, and decided to take up the Dwarves’ 40-days-in-the-wilderness offer at an opportune time.

Before he could, though, tragedy struck.

On the 23rd of December 1970, Kofi had a car accident at Afful Nkwanta in Kumasi. He was riding a motorcycle when he had a potentially fatal head-on collision with a saloon car. He flew off the bike, landing with intense injuries, as the motor got trapped under the car.

This accident occurred just days before the final of the 1970 Africa Cup of Champion Clubs (simply known as the Africa Cup), which is now known as the CAF Champions League.

Kofi, who was then captain of Kotoko, had led the team to the final, and had dreamt of lifting the trophy.

But it wasn’t to be.

Kofi smelled a rat. The accident had occurred at a crucial time. Someone did not want him at that final, he thought.

There is something in football.

“I was once caught up in a trance shortly after the accident where I had a day-dream. I saw a blackboard with the picture of a very close teammate of mine on it. I knew this teammate of mine to be very addicted to juju. Suddenly, someone from behind asked, ‘Osei, do you know this man on the board?’ I said ‘Yes, I do. He has been my ‘boy’ since the 50s’. And the person said, ‘If I told you he was responsible spiritually for your car accident, would you believe it?”

Kotoko, with Kofi’s said teammate being the lynchpin of that side, ended up lifting the Africa Cup on the 24th of January 1971 in Kinshasa, beating TP Englebert 2–1 in the second leg of the final. The first leg back in Kumasi on January 10 had ended 1–1.

Abukari Gariba — who, has to be said, is not the teammate Kofi refers to as causing his accident (Kofi mentioned this teammate by name, but I have deliberately withheld it) — was a popular Kotoko marksman who scored twice in those finals.

Kofi recalls an interesting tradition in the Kotoko team regarding Gariba. “There were times we used to contribute money for him to travel up North to his hometown to ‘buy’ goals from mallams (fetish priests)!” he laughs.

Really?

“Yes, my brother,” Kofi says. “It meant he was guaranteed a goal in those games. Some people believe they can score through juju and superstition. Like I said, there really are things in football.

“Listen: Pastors used to tell me my football talent was a gift from God, so I should stay away from juju protection and enhancements. But this didn’t mean I wasn’t forced to experience it. It was the norm.”

Kofi remembers Gariba once using juju to save him on the pitch. Apparently, one of Kotoko’s mallams, a female, had instructed the team, before a game against Kumasi rivals Cornerstones, to create a circle on the pitch and bury an egg in it, after which a win would be assured.

“Corners caught us performing this ritual!” Kofi says. “Immediately, I knew there would be trouble. One of their players started rushing towards Gariba and I, obviously to beat us up, but Gariba asked me to hide behind him. He took out an amulet from his pants and pointed it at the onrushing player. Before I realized, the player fell to the ground without being touched. I couldn’t believe it. I will never forget what Gariba said. He said, ‘Osei, have you seen that? The fight is yet to start and he’s already down!’”

Kofi has a good laugh recalling this story.

“Boy, I loved Gariba!”

Though Kofi did not get to play in the 1970 Africa Cup final for Kotoko, there was a silver lining to the accident after all.

“I was flown to Munich for an operation,” Kofi remembers. “And while unconscious on the stretcher to the operating room, I had a dream and saw supernatural beings who I believed to be angels. They told me that if I had gone off to the mountains to live with the Dwarves for 40 days, as I was planning to eventually do, I would have gone missing forever. Perhaps that is why God allowed the accident to happen, I thought, because it made me reconsider going.”

He continues: “The angels told me I would be given another chance to play football for the Black Stars for two more years. And it came to pass, as I went to the Olympics in ’72, my last major international tournament, before retiring from the team. I remember that dream very well because I later wrote it down.”

Kofi believes his countless encounters with juju in football made him become born-again.

He recounts the pivotal juju story that inspired him to become a Christian. It is from the early 1970s, years before he finally retired from football in 1976.

After a friendly against Hearts of Oak in Mpraeso, Eastern Region, he discovered another strange injury to his right leg. “I didn’t notice the injury until a friend, who was a policeman in Nkawkaw, pointed it out to me later that evening,” he says. “And immediately he did, I started feeling pain. My leg eventually got swollen.”

John Botwe, Kotoko’s goalkeeper at the time, took Kofi to see his pastor, a man named Nyamekye.

“Nyamekye, upon seeing me, immediately shouted: ‘You don’t believe in God, do you? But because of your injury you are here to seek help!’”

Nyamekye prescribed that Kofi undergo a seven-day fast.

That same day, Kofi recalls meeting a mallam affiliated to a Kotoko official he (Kofi) was staying with. The mallam claimed to be fond of Kofi. “He gave me a special concoction containing honey, and asked me to smear it on my tongue,” he remembers. “He said it would make me powerful. Anytime I talked to anyone in authority, they would do exactly as I said and give me everything I wanted.”

Kofi was in a deep dilemma. Christianity or juju? He was on the verge of being converted to Christianity, and was being tempted by juju, which he was already familiar with due to its perverse practice in football.

“I told myself, which is which?” he laughs. “But I made a decision: God first.”

Kofi says he threw the concoction into an incinerator behind the house, and went to sleep.

“I dreamt later that night that the mallam had eerily entered my room,” he recalls. “He asked, ‘Where is the stuff I gave you?’. ‘I threw it away,’ I replied. ‘If you don’t like it, give it back!’ he said, reaching out to violently pull my hand.”

“I woke up startled, on the floor — I had fallen off the bed,” Kofi adds. “I couldn’t sleep again. I was really scared. I later wrote the dream down.”

On the third day of his fast, Kofi had another vision. The summary of the vision, he says, was that some of his Black Stars teammates were plotting to ‘remove’ him from the right wing, the ‘number 7’ position, through that injury.

“I eventually recovered from the injury after the fast, but that experience made me believe in God. Before then I was not really a Christian. I didn’t believe in anything.”

He would soon become and pastor, and would remain one till date. “My faith in God has grown over the years,” he says. “It has made all the difference. As Psalm 118 verse 8 says, ‘It is better to trust in the Lord than to put confidence in man’.”

After retirement in 1976, Osei Kofi became a stadium manager at the Kumasi Sports Stadium.

In the early 80s, he trained as a coach in Brazil, and came back to coach Kotoko to the 1982 league title. That team, under subsequent coach Ibrahim Sunday — who had been Kofi’s assistant captain in 1970 — went on to win the Africa Cup in 1983.

Kofi would go on to coach many clubs in the ensuing yeats, especially in the lower divisions, alongside his work as a reverend minister.

Kofi reckons that Ghana has not been adequately grateful to him for all of his contributions to the country’s football history.

“In 1965, my prize for Sportsman of the Year was a small TV set, which the soldiers even took away after the 1966 coup,” he says, bitterly.

“I’ve not earned much from serving Ghana. I don’t even own this house I’m living in — I am only looking after it for a friend. I am 84 and I take care of nine people in this household. How do I survive? Only by the grace of God.”

Throughout his career as a footballer, Kofi was a civil servant, working at the erstwhile Farmer’s Council and later as a storekeeper at the National Sports Council.

Kofi used to be given 900 cedis ($60) a month by the state in an arrangement instituted by former Ghana President JA Kufuor during his tenure, but Kofi says he has not received a penny in the last two years.

“The only real benefit I got from serving the nation is this certificate.”

He hands it over to me.

It is State Award; a “Grand Medal, Civil Division”, presented to him by Ghana’s military Head of State, General Ignatius Kutu Acheampong, on the 6th of March 1977, as part of the 20th anniversary of Ghana’s independence.

It calls Kofi an “illustrious citizen.”

“This certificate is all I have,” he says. “It’s sad, but to be honest, it has been of some benefit. It has taken all of my children to the UK — all I had to do was to attach it to their travelling papers and bam, they got visas.”

Does he regret not travelling abroad to play professional football when offered a chance by Stoke City at the height of his career?

That was 30,000 pounds! In 1969! Perhaps his life would have changed.

Kofi is skeptical about what could have been.

“I respected Kotoko’s leadership a lot, otherwise I would have gone,” he says. “They made me a promise to take care of my every need and want if I stayed. Unfortunately, all of them died one after the other in the subsequent years!”

“Well, in all things, I thank God,” he continues. “Life is all that matters. Who knows how things could have turned out for me? Perhaps I could have died, you know? And perhaps I wouldn’t have succeeded, because I was so afraid of the cold! I know a friend who broke down straight after emerging from his flight upon arriving in the UK. The cold was too much for his rheumatism!”

According to Thomas Freeman, Osei Kofi was named Ghana Sportsman of the Year twice (’65 and ’69) and Footballer of the Year four times (’65, ’66, ’67 and ’69). He was top scorer for Kotoko for six straight seasons, and is the club’s all-time leading scorer in the Africa Cup with 12 goals.

How many goals did he score for the Black Stars in the eleven years he featured?

“It hurts that record keeping in my time wasn’t a thing like it is now,” he says, shaking his head. “Because I scored a lot of goals, way more than these modern players have, and I wasn’t even a striker. Once, in 1965, I scored four goals and assisted most of the nine goals as we beat Kenya 13–2.”

Kofi attributes his success to one fact: “I was a footballer — not a football player.”

Is there a difference?

“Yes, there is,” Kofi says, eager to explain.

I listen attentively.

“Footballers are those born with the ability,” he begins. “They are naturally talented, and this phenomenon is often a mystery. They are geniuses — endowed with innate intuition and intelligence. There is visible originality and purity about their technique and skill, and they operate as though it is effortless. They are entertainers, with a certain artistic and aesthetic quality about the way they play.”

Fascinating.

He continues. “Football players on the other hand are those that have learned how to play football. Their gift is not the skill itself, but the ability to acquire it. Exceptional football player are consciously coached in elements of technique and train hard to become masters of the trade. I’m not saying they are inferior — indeed some of them even end up being more successful than footballers. But you can clearly see the difference. I always use Messi and Ronaldo as examples. I believe Messi is a footballer, while Ronaldo is a football player.”

It’s been 42 long years since Ghana last won a major international title — the 1982 Afcon in Libya.

Kofi’s prime coincided with Ghana’s golden era, with many highs — four consecutive Afcon finals from 1963 to 1970, two of which were won; the first African side south of the Sahara to qualify for the Olympic Games; that landmark 3–3 draw against Real Madrid, and many others.

Ghana was a powerhouse in world football, and only missed out on featuring at the 1966 World Cup because of an African boycott, led by Ohene Djan. Who knows: Kofi could have met Gordon Banks two years earlier at the World Cup in England, and could have made his name on the big stage.

“We had a lot of real footballers in my time,” he says. “People have said that Ghana is gifted with natural talents, and it is so true, more so during my time. The quality was unreal.”

Kofi says it is no coincidence that all the generations that won Ghana its four Afcon trophies were amateur players.

“We played with unity, as a team, and for the love of the game,” he says.

“The current generation have allowed ‘professionalism’ to eat into their character. They play individually to sell themselves for contracts and not for the team or for nation.

“It will take a while — and a lot — for us to win anything again.”