The tale of Kwame Nkrumah and Real Madrid

In August 1962, the world’s greatest football club came to Ghana, in a remarkable story that was as sporting as it was political, writes Fiifi Anaman

He remembers it so well.

How he got to the gate of the Accra Sports Stadium after a long, tiring bus ride from Kumasi. How he saw the security man who barked at him to stop in his tracks.

It was August 19, 1962.

“Where is your ticket?” the security man gruffly demanded of Dogo Moro.

Moro was disappointed.

Inside the stadium, his teammates, the best footballers in Ghana, were warming up, about to play what was going to be the biggest game in the country’s football history. Yet here he was, a star of the team, struggling to be recognized at the box office.

But the disappointment would only prove fleeting. The fans, who knew who he was, who adored him, would come to his rescue.

“Do you not know this man? Do you not know?! How!?” they howled, scolding the reluctant security man into submission.

Dogo Moro then joined the loud crowd into the stadium, where close to 30,000 others had consumed the stands with their presence, hijacked the atmosphere with roistering.

The Blacks Stars of Ghana were about to play the biggest team in the world.

Real Madrid were in town.

The highly rated Dogo Moro, who had been a part of the national team since 1958, had been banished from the team because he had betrayed Ohene Djan, Ghana’s powerful Director of Sports.

The back story ran deep.

Ohene Djan — on the instructions of Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s founder and first President — had set up a club called Real Republikans early in 1961.

Nkrumah’s dream was to have a ‘model club’, a side that would be star-studded with Ghana’s finest footballers — a sort of shadow national team — capable of commanding international respect. He wanted a club that would transcend the duopoly of Asante Kotoko and Hearts of Oak, Ghana’s biggest and most successful clubs.

The inspiration for the club’s name and general model came from Real Madrid — an institution Nkrumah long admired.

And so Djan, who knew how to get what he wanted, went about raiding Ghana’s top clubs — Asante Kotoko and Cornerstone in Kumasi, Hearts of Oak and Great Olympics in Accra, Hasaacas and Eleven Wise in Sekondi, Mysterious Dwarfs and Venomous Vipers in Cape Coast — each for their two best players.

Dogo Moro, along with his friend, the legendary winger Baba Yara, were considered to be the best players at their club, Asante Kotoko, and so they were drafted into the Republikans side ahead of the club’s debut in the 1961/62 Ghana League season.

The duo’s departure from the fold of the Porcupine Warriors, prided as the ‘Idol Club’ of the Ashanti Region, would spark a dramatic crisis — a beef pitching the Djan-led Central Organization for Sport (the country’s sport-controlling body) against the Ashanti Region’s top football executives.

The tension was intense: Djan even threatened to sack Kotoko from the Ghana league following their threats to boycott it in protest of the poaching of Moro and Yara. “Our officials at Kotoko were very cantankerous in those days,” Moro explains. “They didn’t see eye to eye with Djan at all.”

Worsening the rift was the fact that Republikans were minted in Nkrumah’s image: The club was nicknamed OOC — Osagyefo’s Own Club. This tag qualified them to become one of the subjects of the long-running cold war between the Nkrumah-led Convention People’s Party government and its main opposition, the United Party — concentrated with the Ashanti Region’s top politicians.

Republikans, unsurprisingly, became the subject of endless controversy, the target of hatred from fans and stakeholders alike, due to their mode of recruitment as well as the high echelon support and protection they enjoyed. All across the country, they were shunned and panned by fans.

At the end of their first season, however, Djan made some changes. The seeming arbitrariness of the team’s recruitment method had caused too many problems. And so he dissolved the playing body of the club for subsequent reconstitution.

Players who wanted to stay, as well as prospective ones who wished to join, were asked to submit applications. It was a fresh start, and Djan loosened things up. He opened the exit doors for existing squad members who no longer had the strength to endure the backlash to leave on their own volition. Secretly, though, he demanded some loyalty from his stars. He quietly wished that none of them would walk away.

But some would. And little did he know that among them would be Dogo Moro, his beloved central defender and close friend. “Djan was hurt, because I was so close to him,” Moro recalls, five decades on. “He believed in me so much and I sort of disappointed him.”

“But I had to leave,” he continues. “The conflict was too intense and I remember how some officials back at Kotoko had rained warnings and threats on us. I really couldn’t deal with the trouble of another season.”

That decision would cost him an arm and a leg. Djan, a notoriously highhanded politician, would punish him by ending his international career, making him a pariah as far as the Black Stars were concerned.

And so here he was, in the stands on a hot August afternoon, nursing the pain of seeing his teammates prepare to take on Los Merengues — club football’s gold standard, a side feared and revered — without him.

Ohene Djan, who shot to sporting stardom by becoming the chairman of Ghana’s Amateur Football Association in 1957, was tasked by Kwame Nkrumah to make Ghana football “a showpiece on the African continent.”

A radical go-getter, he immediately got to work on many revolutionary policies that would later come to define his tenure as the ‘Reformation Era’. One of such policies was the invitation of top football teams into the country to play Ghana’s national team, the Black Stars: an institution he founded in 1959.

Djan wanted the Black Stars to rub shoulders with football royalty; not only to learn, but to ultimately become royalty too. He used his connections and resources to pull top clubs such as Austria Vienna, Fortuna Dusseldorf, Blackpool and Dynamo Moscow, all in a bid to sharpen the Stars for the ultimate goal of global prominence. To prove his seriousness, Djan, in the summer of 1961, took this policy up a notch: he engineered a 12-match tour of Eastern Europe for the Black Stars, making Ghana the first Sub-Saharan country to tour that side of the Iron Curtain.

Real Madrid had always been a target within this scheme, but the idea remained a mirage for months, mainly because of how high profile they were. There were doubts, largely owing to their colossal economic and political clout.

Aside that, their CV was loaded and lustrous: eight-time champions of Spain, 10-time winners of the Copa Generalissimo (now Copa Del Rey) and, more markedly, five-time winners of the European Cup: club football’s most prestigious tournament, one that they had monopolized since its first edition in 1956, through to 1960.

Further evidence that they were a symbolic representation of excellence in football lay with their playing body. Within their ranks were the world’s leading footballers, chief among them Alfredo Di Stefano and Ferenc Puskas: professionals with a perfected craft, superstars paid ubercash, the Beatles of the beautiful game. “To chronicle the Real Madrid team is to chronicle greatness,” the great British sportswriter Hugh McIlvanney once wrote.

When Real Madrid beat Frankfurt 7–3 in the 1960 European Cup final at Hampden Park in Scotland, by a performance football connoisseurs rank as among the finest ever by a club side, McIlvanney wrote that the crowd that day had been “moved by the experience of seeing a sport played to its ultimate standards.” “Here was the game as it could and should be played,” the Fleet Street veteran later added. “It was a watershed for me, as it was for so many.”

In 1962, Djan finally managed to crack the Madrid invitation code by using Josef Ember as a bridge.

Josef Ember was a Hungarian coach Djan had hired in 1960 to coach the Black Stars. Soft spoken yet immensely knowledgeable, the sexagenarian had trained Real Madrid’s Ferenc Puskas at youth level, and so Djan capitalized on this link to initiate contact and correspondence with the Spanish giants.

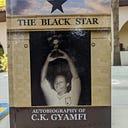

Eventually, when things started to pick up, Djan relayed the responsibility of negotiations unto Charles Kumi Gyamfi. C.K Gyamfi was a former Black Stars captain who Djan had made Ghana’s first black national coach in January 1962, following the promotion of Josef Ember to the position of Technical Advisor.

On Thursday, July 12, 1962, Djan sent Gyamfi on an errand. He asked him to go to Spain’s capital to meet and hold final negotiations with Santiago Bernabeu, Real Madrid’s prominent president. Djan knew of Madrid’s tentative plans of touring Africa in the summer of 1962, and he wanted Gyamfi to convince Bernabeu to include Ghana in his plans.

Was it going to work? Djan was upbeat. Gyamfi was a trusted associate of his. He trusted him so much as to to make him Ghana’s national coach at the age of 32, at a time when it was strange for an African nation to have an indigenous trainer. He had the utmost confidence in the leadership qualities of his man, just like the way Nkrumah had in him (Djan).

Gyamfi returned from Madrid a few days later, on Monday July 16.

So?

What now?

Were they coming?

The Daily Graphic had the answer: REAL MADRID FOR GHANA NEXT MONTH, said a story announcing the good news.

Gyamfi had delivered.

Game on.

This was huge. A victory even before they landed.

Though they were at least seven years into their first, original ‘Galacticos’ era — a period where Bernabeu had basically assembled the world’s biggest stars bar Pele in an effort to make his team club football’s gold standard — Real Madrid were still not past their peak.

Ghana had thus managed to get them to come into the country at a time when they were still relevant and red-hot. They had wrapped up their 1961/62 season with a domestic double, clinching the 1962 Spanish League and Cup titles. It could have been a treble too, but for a loss in the 1962 European Cup final in Amsterdam, coming at the hands of Portuguese giants Benfica, then coached by the enigmatic Bela Guttman and led in attack by the great Eusebio.

At the press conference announcing Madrid’s impending visit, Djan revealed to a group of excited sportswriters that his COS outfit had agreed to foot close to a quarter of Madrid’s African tour bill, a budget that ran over £65,000, just so they could put Ghana on their list. He meant business.

In truth, £15,000 was a tough amount to cough up, but Djan put his foot down not only in finding the money, but also in finding a defence for it as well. In his view, this expensive commitment was necessary because the visit of Madrid would add an immeasurable amount of value to Ghana’s football. Alluding to the 1957 Ghana visit of Sir Stanley Matthews, the English football legend, Djan said that Madrid were “a team of eleven Matthews.”

Basically, he was expecting the Spanish club to leave a trail of impact that would be many times that of Matthews’ — which had been an eventful visit in whose wake Ghana adopted modern football methods, paving way for a significant boom in growth.

“Our interests in arranging this fixture is not to win,” Djan explained. “But to give our players a unique opportunity of rubbing shoulders with the best in the soccer world and to improve thereby.”

The Daily Graphic agreed: “This is the most precious service the COS can render to Ghana football,” it wrote. “To see the soccer wizards of Real Madrid play is both a treat and an education; to battle with them for 90 minutes is to have undergone a three-year coaching course. This visit is destined to revolutionize Ghana football.”

The footballers weren’t going to be the only beneficiaries. The fans were going to be big winners too. A large chunk of Ghana’s over seven million population then were football-obsessed, and they certainly knew how much of a big deal Madrid was. They had read and heard about their exploits, forming a mythical connection to them, seeing them as otherworldly entities who were unencounterable. Thus their imminent advent threw the fandom into a state of frenzied anticipation, dominated by a star-struck, pinch-me sense of surreal excitement.

“Real Madrid is a tough team and I want to congratulate the C.O.S for making it possible for soccer fans in Ghana to see them in action,” the Graphic added.

The fans were going to see Madrid in action, but the players were going to compete against them, and Djan made sure his boys never lost sight of this. He put in place an intensive selection and training program ahead of the game, an effort that made no secret of one fact: He didn’t want the Black Stars to hide behind the guise of a friendly to disgrace themselves.

Past form was rubbished: no national star was going to make the team based on reputation. To access the room of selection, everyone was going to go through the audition door, a justify-your-inclusion session spread over a series of trial matches that Djan dubbed “Soccer Maneuvers".

Well, everyone except players like Dogo Moro or Kumasi Cornerstones’ midfielder Joe Aikins — a duo whose withdrawal from Republikans, in Djan’s stern books, meant they had appended their signature on a restraining order preventing them from coming within any distance of the Black Stars.

After the Maneuvers, 21 players were selected into camp, under the guidance of national coach C.K Gyamfi, Ashanti Regional coach Kwame Appiah and the COS Technical Advisor Josef Ember. From this lot, two teams were formed: the first, named ‘Possibles’, comprised of the top players tipped by many to start against Madrid, while the second, named ‘Rest of Ghana’, was made up of fringe players.

Both teams were pitched against each other in a training game that was billed to last 110 minutes instead of the usual 90 — a deliberate move geared towards building the stamina of the boys. The COS was approaching a friendly game with the preparation of a World Cup final.

C.K Gyamfi and Kwame Appiah were drafted into the Rest of Ghana team as player-coaches, though both were old and semi-retired, mainly because the COS wanted to access all the experience and expertise they could get their hands on. “These two coaches have been keeping fit all the time and it seems they have not outlived their usefulness as possible choices,” the Ghanaian Times wrote in defence of this decision.

In the end, Gyamfi and Appiah, a duo who had their hey day back in the 50s — Gyamfi as a lethal striker and Appiah as an impermeable defender — true to the assessment of the Times, did indeed prove that they still had some football left in them. They spearheaded the Rest of Ghana team to an upset, beating Possibles 4–2.

People weren’t pleased. A team supposed to be a backup plan had beaten one that was supposed to be mainstream. Plan B had proved better than Plan A. Public confidence was shaken. Even to the brink of the panic. “Of course, our main aim of playing Real Madrid is not to win but to acquire experience,” began a Daily Graphic writer in a column. “However, we must be able to create a favourable impression that we are a soccer force to reckon with. That is why I don’t hesitate to say that the performance of the Stars is alarming and calls for a complete overhauling of the team.”

In the aftermath of the game, what happened was not quite the overhaul that the writer requested, but certain changes were made by the selectors in fine-tuning the squad.

The last trial game that was played was treated with seriousness. The Times called it “Survival of the Fittest”, and the massive attendance it enjoyed would have made anyone mistake it for the actual fixture.

The COS continued to experiment with changes. The name Possibles was changed to ‘Old brooms' whilst Rest of Ghana became ‘New Horizons’. There was some cross-over of players too: alongside player-coach C.K Gyamfi, the young and menacing Asante Kotoko wingers Osei Kofi and Kwame Adarkwa — both of whom were making waves in the Ghana league as ‘wizard dribblers’ — were transferred from the New Horizons to the Old Brooms. This decision would prove crucial: one of these players would go on to start and score in the big game.

This last trial game was handled as some sort of dress rehearsal to fix all possible problems, and so it was probably a good thing that the COS eventually discovered one: the fans. Perhaps it was the anxiety, but they proved disturbingly rowdy and judgmental, barely cheering their favourites and clearly jeering the ones they felt weren’t worthy of a Black Stars berth.

Most of these fans, as expected, were anti-Real Republikans, and so their demeanor was an overly defensive one, in an effort to resist what they felt was a conspiracy by Djan to force players from Nkrumah’s pet club into the team. Their abusive attitude towards some players bordered on hooliganism, and this atmosphere of negativity left Djan miffed. He didn’t like anything messing with the focus of his team ahead of their match of destiny. “It is bad and unpatriotic,” the Sports Chief fumed. “The COS had hoped that fans would have placed the interest of the nation above that of their clubs.”

These fans had been able to access the game due to being in possession of advanced tickets for the main event, which had gone on sale days before and had sold out with lightning speed. Worried that their unruly behavior might just portray a damaging image, Djan announced plans to tighten security at the gates on matchday. He said that all “ruffians and club fanatics” would be ostracized without hesitation, and not even “the mere possession of a valid ticket would not be tolerated as a licence to undermine” the Black Stars.

The security on match day, true to Djan’s promise, would prove very sensitive: just ask Dogo Moro.

Real Madrid, with their bags and jet lag in tow, touched down in Ghana on Friday August 17, 1962 — two days before the game, to afford them time to relax and acclimatize.

Their advent brought the nation to a standstill, hijacking the front page of the Daily Graphic — the biggest newspaper in the country — sacking all the politics.

It was football time. History season.

REAL MADRID STARS ARRIVE, the headline exclaimed, accompanied by a panoramic photo of their casually dressed contingent of 15 players and six officials taking a stroll in front of their adopted residence, the Ambassador Hotel — now Movenpick Hotel — in central Accra.

It was a base that was conveniently situated a few blocks away from the Accra Stadium. “Here they are, the architects of modern soccer — stars of the fabulous Real Madrid football club,” read the Graphic’s caption, barely concealing their representation of a nation entranced in hero-worship.

“Soccer legends Real Madrid, you are welcome to Ghana!” they wrote in their sports section.

If you thought this praise-singing tone was enough, then check this out: “On behalf of thousands of sports fans in this country, who no doubt, will be at the stadium on Sunday to see and admire your great exposition of delightful artistry for which you are universally famed, Graphic Sport welcomes you to Ghana. To us, it is a great honour that Europe’s number one club, the super club of the world, should accept our invitation to visit our young republic.”

It was clear: Graphic had thrown self restraint out the window. They — like everyone else, especially the Times (“Madrid are eleven maestros in every department of the game”) — were in awe, carried away by the fever of this once-in-a-lifetime event.

Meanwhile, the C.O.S had named the strongest Ghana team possible:

Dodoo Ankrah (goalkeeper), Franklin Crentsil, Charles Addo Odametey, Ben Simmons, E.O Oblitey, Kwame Adarkwa, C.K Gyamfi (player-coach), Edward Aggrey Fynn (captain), Baba Yara, Edward Acquah and Wilberforce Mfum.

On the bench were goalie De Graft, defender George Appiah, as well as youngsters Osei Kofi and Agyemang Gyau.

The COS’s Technical Advisor, Josef Ember, was confident with the lineup. “I am pleased to have virtually the same attacking machine which the Black Stars used during our successful tour of Eastern Europe last year,” he said. Ember, as coach, had led the Black Stars to eight wins amid 12 matches played on tour across the Soviet Union, West Germany, East Germany and Czechoslovakia.

One would have expected Real Madrid to be cocky and field a second string side, but they weren’t in the mood to, as Ghanaians love to say, “loose guard.”

The home team had made it clear that this was only going to be a friendly game on paper, but anything but on the pitch, and Madrid were apparently on the same page. They hadn’t come to Accra expecting a stroll in the park. They weren’t going to let a group of amateur footballers from a five-year-old country use them as a headline grabbing ticket. The Black Stars of Ghana weren’t going to use Real Madrid as a springboard to global fame.

“This is football and anything can happen,” Bernabeu cautioned on their arrival. “We will play all our best, as expected of a leading club in Europe. We have in mind that we will be up against a strong country.”

Bernabeu had done his research. He knew that Ghana was fast gaining a reputation on the African continent as a side on the rise, making strides far and wide, and so risking complacency wasn’t wise. They were not going to make excuses too: not even the infamous heat of Ghana’s climate was going to be a problem for them. “It is hotter in Spain at this time of the year so I don’t think the weather here will have any effect on our players,” captain Alfredo Di Stefano assured.

Their coach, Miguel Munoz, named a strong squad: one that was fully featured the top arsenal in their armoury. Madrid had come into the country with eight players who had been a part of Spain’s squad at the 1962 World Cup in Chile.

Against Ghana, though, they would go on to name a lineup that contained as many as six of players who started the 1962 European Cup final in Amsterdam: Jose Araquistan, Pedro Casado, Jose Santamaria, Enrique Perez ‘Pachin’ Diaz, Ferenc Puskas and Alfredo Di Stefano (captain). Joining them were Lucien Muller, Ignacio Zoco, Amancio Amaro, Yanko Daucik and Manuel Bueno

Their intentions were clear, the Black Stars weren’t going to be spared. And they wasted no time in implementing those intentions too, once referee Frank Mills, Ghana’s first FIFA referee, blew the whistle for the start of the game.

The Spanish champions charged out of the blocks, asserting their well-known authority, pinning the Stars to their own half. As the Ghanaian Times would later write, the Black Stars, in the first ten minutes, displayed “doubtfulness in defence” amid Madrid’s “hurricane start”. The Ghanaians hadn’t known what had hit them: they were disorganized and destabilized.

But this early pressure from Madrid wouldn’t last long. It would wane, and the tides would change: the Black Stars would recover and find their feet against the run of the play. Captain Aggrey Fynn, hailed by fans as a ‘Professor’ of playmaking, the only other person in the land who shared Nkrumah’s nickname ‘Osagyefo’, found the prolific Edward Acquah in the 7th minute with a well-weighted pass.

Acquah, a well-known goal machine, planted the ball at the back of the net with one of his trademark shots. These shots were so powerful and so out of this world, the legend goes, that they had earned him the nickname ‘The man with the sputnik shot’. (Sputnik was the earth’s first artificial satellite launched by the Soviets in 1957).

The deadly Acquah had made his name by scoring all five goals when the Black Stars blacked out Blackpool by a 5–1 score in May 1960. He was a simple striker who didn’t entertain any colourful showboating — the football version of small talk. He was straight to the point: no beating about the bush, just cryogenic finishing.

Interestingly, before the game, the Graphic had written a stern warning to the Black Stars: “This is the occasion to be great, and to achieve this against such a highly skillful side, you should be business-like and purposeful. There is nothing to be gained by indulging in excessive dribbling and playing to the gallery.”

It was thus apt and poetic that Acquah, a man who was all business and all purpose, opened the scoring. And, as if anyone expected any less, he proved threatening a few minutes afterwards with a 40-yard hit, almost powering the Stars into what would have been an unbelievable two-goal lead, but the post stood in the way. The Black Stars were by this time suddenly “riding a high crest of waves”, as the Times claimed.

Real Madrid, sensing danger, upped their game and regained their place in the driver’s seat, dictating the pace. They revved up the pressure some more till a goal arrived the 30th minute: a Puskas header flying past Ghana goalie Dodoo Ankrah.

1–1.

But, just 10 minutes later, the Black Stars were back in front. Sharpshooting striker Wilberforce ‘Bulldozer’ Mfum, who in 1963 would raise eyebrows by tearing tearing the goal net with a shot at this same venue, set Kwame Adarkwa up to take the score to 2–1.

Heat.

The game was on fire, and 22-year-old Adarkwa, a Rest of Ghana/New Horizons boy, was having a belter. “Right winger Adarkwa featured prominently, showing all the tricks of a master, weaving through the visitors’ defence with grace,” the Graphic wrote. He would later get injured, but would be applauded by the appreciative crowd as he made his way off the pitch for his Kotoko teammate Osei Kofi.

Real Madrid, meanwhile, were struggling to come to terms with the fact that the Black Stars were proving way better than they imagined they would be. They bludgeoned the Stars with onslaughts, and though missing the authoritative air of Dogo Moro, the heart of Ghana’s defence — starring youngsters Addo Odametey and Ben Simmons, complemented by the experienced legs of C.K Gyamfi in defensive midfield — held their own.

Madrid grew frustrated by serially hitting dead ends, being kept out. So frustrated, in fact, that when Puskas was put through on goal and was whistled offside, he charged towards referee Frank Mills in fury and Zidane’d him, 44 years before it became a thing.

Puskas head-butted Mills, by the way, for those still at sea with the odd metaphor. His reaction had been an eruption of bottled-up agitation: Madrid had been chasing a game that seemed to be eluding them with every passing minute, and their efforts — like striker Yanko Daucik’s headed goal that was ruled offside minutes before Puskas’ own offside call — seemed not to be hitting home.

Mills, taken aback, pointed to the bench, as if to show the stocky, hot-headed Hungarian his way off the pitch. Shockingly, though, Puskas refused to leave the field.

Captain Di Stefano rushed to the scene to hold pacification talks, after which Mills decided to let go, but the Times were disappointed in his inability to stand his ground against a superstar. They felt the well-respected referee had been bullied into intimidation. “Mills displayed an unfamiliar weakness,” they wrote. “He must have considered that it was a goodwill match. But goodwill matches are controlled by the same set of laws and there could be no bigger affront to these than to permit a player who assaults a referee to continue play.”

Mills disagreed, felt slighted. He sensed condescension, an attempt to underrate him. In a rebuttal, he wrote that the Times had “tarnished” his reputation with their observation and comment, saying Puskas only “attempted to hit me on the chest with his head.”

“I took strong objection to this ungentlemanly behavior of his, and after calling him, I cautioned him seriously,” he began, in a narration of his side of the story. “In cautioning him, I pointed towards the gallery and said: ‘If you behave in this ungentlemanly way again, I shall have no hesitation in showing you the dressing room.’ Pointing my hand towards the gallery did not mean I was sending him off. Demonstrating with a show of hand to indicate that a player would be sent off the field does not necessarily mean that he has been ordered off. Puskas or no Puskas, I would have ordered him off if I meant to do so, and no power on earth could have influenced me to rescind my decision.”

“I was shocked when the incident occurred,” Bernabeu would admit later. “I never expected Puskas, with his long experience in the game, to behave like that. However, I think he did that under high provocation.”

Back on the pitch, Madrid were sweating in their search for parity.

They kept pushing, and a reward came on 75 minutes when they worked their way into a goal-mouth melee, one that was forced in by a leg that either belonged to Amancio Amaro (Graphic’s report) or Ignacio Zoco (Times’ report).

2–2.

At this point, a draw would have been huge for the Black Stars. Surely, they were going to defend this result till the final whistle?

No.

The Black Stars knew their worth. They knew no mediocrity, only ambition. They knew no intimidation, only spunk. Like the Times had advised before the game — “Attack! Attack! Attack!” — the Ghanaians poured forward, dissatisfied with the score line, swarming the half of Madrid in a relentless search for a winner.

They saw a historic victory within their grasp, and though the game had traveled deep — limbs succumbing to fatigue, transforming sprints to limps — they were still bent on getting there.

And so they went at the Spanish, drilling deeper, attack after attack, until they struck luck. Edward Acquah, proving to be the man for the big occasion, a man Nkrumah would later describe as “Ghana’s greatest match winner”, turned up three minutes from time to score a goal whose celebration shook the very foundation of the Accra Sports Stadium.

The Black Stars were actually beating Real Madrid. It was unbelievable stuff, dreams unfurling beautifully into reality.

But somehow, the win didn’t happen. The Black Stars over-celebrated the goal and were caught taking a vacation from concentration. Daucik, earlier denied a goal, had his second go, becoming two-time lucky. He connected with a pass from Puskas to pull even just before full-time.

A win had been so close, yet hadn’t happened.

So, were Ghanaians let down?

“Ei, are you serious? How?!”

This is Dogo Moro, laughing.

Basically, Moro says, there was no reason to be disappointed. Expectations had been far exceeded. Never had a draw been that celebrated. The crowd went wild. The stands were filled with joyful tears and wonderful cheers.

The gulf in reputation had not had any bearing on the result — a reflection of the remarkable events that had unfolded on the Accra Stadium pitch.

“Everyone thought they would thrash us by at least 10 goals!” Moro recalls, smiling. “Yet we were leading with a few minutes to go! Can you imagine? Leading against Real Madrid — the best team in the world! Leading against Di Stefano and Puskas! The boys played so well! They did us so proud that day.”

Argue that the celebration of a draw was bizarre and you would be right, but consider the stakes and you’ll realize the true victory lay in the fight. The Black Stars had gone into the game hoping to learn many things, most likely amid a sound beating, but they came out as the better side in a pulsating encounter, minutes away from a win.

Think about it.

On the pitch in Accra, the Black Stars redefined bravery by humanizing the gods of Madrid with a heroic performance. For Madrid, this was a humbling moment of worry, a memento mori, because they practically assumed immortality any time they came up against teams that were many floors below their elite penthouse.

While other teams squinted with discomfort at the severe brightness of their stars, the Black Stars stood wide-eyed in defiance, refusing to bow at the sight of their greatness. Captain Aggrey Fynn said it best when he claimed after the game: “Although we had great respect for Real Madrid, we were not disturbed by its enormous reputation.”

Rather than be disturbed, the Black Stars chose to bring down the white stars from their celestial realm of invincibility, forcing them to work and sweat, to confront their fears and weaknesses. Bernabeu was impressed. “Your players exhibited the highest performance I have seen of any African team,” he praised. “I was highly surprised.”

Di Stefano, too: “It was a really good game,” the Argentine legend told pressmen after the game. He said his teammates had not expected such a “difficult” opponent, and that they realized in the course of the game that the Black Stars’ standards were “very high indeed.” “Your players are too advanced,” he confessed. “They compare favourably with most of the leading clubs we’ve played against.”

What about the Press?

Just imagine.

The Daily Graphic was overwhelmed with joy, waxing lyrical. “Ghana is now world class!” it boldly proclaimed in the opening line of its report. “Real Madrid played artistic soccer and were fast. But against such a determined force as the Black Stars, they met their match,” added a columnist. “They will never forget the tough opposition they had from the Black Stars. The time has come when the attention of the entire soccer world must be focused on Africa. Let them go back to Europe and issue a warning to all top soccer clubs!”

The Times on the other hand weren’t as effusive, but they definitely weren’t going to miss the significance of what had transpired. “The Black Stars proved to the 30,000 spectators who jammed the Accra Sports Stadium that they are now ripe to take part in all forms of world competitions.”

Ohene Djan?

He was delighted.

Never one to be bashful, he was all boisterous optimism. He had put in a lot of work to see such fruit, such pride-evoking statements, yet he wanted more. “The performance of our boys will spur us on to greater achievement,” he said after the game. “We will however not rest on our oars. We shall continue to organize and train until Ghana becomes a top ranking soccer nation.”

For Djan, the ‘victory’ brought vindication too. One of the biggest talking points that emerged from the game was the pivotal role Real Republikans played in the result. All but just two of the players that played against Madrid had been Republikan players, and the telepathy had been evident too.

“There was complete understanding among the players,” the Graphic observed in a review. “And it was quite easy for them to exhibit many moves harmoniously.” This was because the players, through Republikans, had gotten a chance to camp, train and play together for over a year, forging a deep, effortless chemistry that the Black Stars benefited from. This had been one of the prime reasons behind the club’s formation: to serve as a sort of Black Stars mirror, an alternative, in order to develop cohesion among national players.

Thus, after that inspiring performance against Madrid, it felt like humble pie time for the opponents of the club, fulfillment on the other hand for the proponents. Inevitably, a debate emerged: maybe it was time for the public to let go of all the resentment towards the Republikans. Maybe it was time to accept them, because after all, the idea behind the club’s formation was steadily beginning to make sense. The Graphic led the conversation: “Let’s support Real Republikans,” a headline pleaded. “Ghana needs a strong national team.”

Real Republikans, though, continued to be starved off public support and ended up having a very short life span — it barely made it past half a decade. From its establishment in 1961, it went on to win one Ghana League title and four FA Cups, all against the odds of public hostility, but it wasn’t their success that mattered: it was the blood they supplied the Black Stars, that critical lifeline, that endured and outlived them.

When the team was disbanded after the 1966 military coup that overthrew Nkrumah, the Black Stars felt the loss: they went into a wilderness of trophylessness for over a decade.

At the Flagstaff House, the President of Ghana was over the moon when Real Madrid’s contingent paid a courtesy call on him before jetting out of the country.

Nkrumah, whose well-known passion was asserting Ghana’s authority globally, lauded the Black Stars’ “sparkling performance against Europe’s number one club.”

“To have held the fabulous Real Madrid to a 3–3 draw is a proud achievement,” he said. “Considering the fact that the Black Stars are all bona fide amateurs, I am certain that they have compelled the soccer world to acknowledge the fact that a new soccer force has arisen along the West coast of Africa.”

“Your reputation in the field of soccer is enormous,” Nkrumah told Santiago Bernabeu de Yeste, the President of the club he wanted his Republikans to emulate.

The pot-bellied Don Santiago seemed to be bonding with Nkrumah, having a hearty conversation while presenting him with a souvenir: a breastpin featuring Real Madrid’s emblem. “Having given the Black Stars the opportunity to rub shoulders with you is an inspiring gesture,” Nkrumah thanked.

Bernabeu, a man who had spent the last 19 years building Madrid into a world power — since his ascent to the presidency in 1943 — gave Nkrumah hope for his own ambitions. And although neither the Osagyefo nor his own club would last long enough to achieve what Bernabeu was able to do, the Black Stars ultimately hit high heights to make up for it all.

At the meeting, Madrid skipper Alfredo Di Stefano was awed by Nkrumah’s interest in football, in his club, in his national team. “Few heads of state are able to combine state duties with sports,” he remarked.

But that wasn’t the only thing he had been impressed by during his club’s visit.

After the game in Accra, Di Stefano had told pressmen:

“I must admit the Black Stars have a really bright future in football.”

These words were merely an observation, but they would morph into a prophesy. The performance that day offered the strongest indicator that the Black Stars had it in them to go on to do great things.

And they did.

The year afterwards, 1963, they won the Africa Cup for the first time. A year later, they became the first Sub Saharan African nation to qualify for the Olympics, impressively going on to reach the quarter final in Tokyo. A year after that, they became African champions again. Experts argue that the only thing that prevented them from making the World Cup in 1966 was Africa’s outright boycott in protest of the unfair treatment meted out to them by the Stanley Rous-led FIFA administration.

By the late 60s, barely a decade after its formation, the Black Stars had become Africa’s most respected football team, labelled with the prestigious yet burdensome moniker: “Soccer Emperors of Africa.”

It is a reputation that subsequent generations of Black Stars would continue to benefit from: a reputation so solid and so powerful that it still defines the team, even after 40 years without a trophy.

Originally published at https://www.pulse.com.gh on September 21, 2016.