Your Legacy Lives On

Ghanaian football superstar Christian Atsu’s devastating demise uncovered a lasting legacy that will outlive him for ages to come, writes Fiifi Anaman

Ekinci, Inönü Boulevard,

№ 57 Antakya,

Hatay,

Turkey.

Christian Atsu Twasam began his day in a way that was typical of the man he was — with God, a prayer, and with family, a call. It was the morning of Saturday February 4, 2023 in Antakya, located in the Hatay Province in southern Turkey.

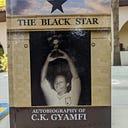

Atsu at this point was a professional footballer for Turkish top flight side Hatay Spor Kulübü, simply known as Hatayspor. He was also a semi-retired member of Ghana’s senior national football team, the famous Black Stars, having won 65 caps with 9 goals between 2012 and 2019.

He was at home, an apartment in a plush, popular building called the Rönesans Residanz (Renaissance Residence).

What was the Rönesans like?

Picture the Polo Heights building in Ghana’s capital Accra, which is situated a few miles away from the Kotoka International Airport, where Atsu frequently flew in and out on business class flights, and where 14 days later he would arrive in ‘cargo class’ as a corpse, received by members of Ghana’s press and political corps.

More on that morbid story later.

Now, on that Saturday morning, Atsu, after routine prayer — “God is my life; my everything” he once told ETV — placed a call to Newcastle upon Tyne, England, over 4,600km away.

This was where his nuclear family was based.

He was calling, as he often did, to check up on his wife, the German-born author Marie-Claire Rupio, whom he met and married in 2012, and his three young children, two boys and a girl.

This was a close-knit family he once described in an interview with TV3 as the “best trophy” he’s ever won, both in his life and in his career.

Later in the day, Atsu sent an email to Ellie Milner, the co-founder and Executive Director of the UK-based charity Arms Around The Child (AATC).

Atsu, a generational gentleman of generosity, was a global ambassador — a benefactor, more appropriately — for the organization, which caters for deprived, abandoned and orphaned children, in order to combat child labour, trafficking and poverty. It operates in India, South Africa and Ghana.

Atsu had once heard about the organization through one of its volunteers during his time playing in England, and without questions, had simply said: “Let’s do it! Let me help you!”

And so just like that, Christian Atsu got on board, getting to spread his arms around many children with alms giving. From then, he would consistently send truckloads of goods and food and other supplies to the children the charity was taking care of in Ghana.

He helped provide water and shelter. He would bring them footballs and boots and other apparel on his visits, then he would play with them. He brought them gifts such as books and stationery. Sometimes, he would take them on shopping trips.

In this email, Atsu told Milner that he was sending more funds over to further support their current project: the construction of a school in the small village of Senya Bereku, in Ghana’s Central Region.

Atsu said he really wanted to see the school finished soon, and that he was “so pleased” with the progress made. The school’s construction had begun after a successful fundraiser in March 2018. It was set to admit over 300 children when completed.

Five hours later, Milner received yet another email from a buoyantly impatient Atsu.

Why don’t they move the opening of the school to June 2023, he suggested. That way, he wrote, he would be able to make it the memorable opening ceremony that the project deserved.

June would also be in the summer, and that would mean vacation time for most of his Black Stars teammates, some of whom he would be able to invite to the opening.

Atsu was excited, expectant.

Milner was too.

Prologue

In Ghana, there is a famous saying, attributed to an anonymous person, and often mentioned at funerals, that says: “The cause of death is birth.”

The moment a man is born, death becomes certain, and it only becomes a matter of time — time that no mere mortal can ever predict from birth.

Here’s how you know that when death is meant to happen, it will surely happen, no matter what you do.

When the time comes, nothing can save you.

You will surely go.

Doubt it? Well, take your time to analyse events that lead up to certain deaths.

Just take a close look at the trail of detail, the trajectory leading to the tragedy.

The following story is one example.

Here we go.

The next day, Sunday February 5, 2023, Atsu got ready to play in what was going to be his last match for Hatayspor, a club he had joined on a one-year contract in September 2022. He was going to say goodbye to Turkey.

Since joining the club from Saudi side Al Raed FC, Atsu had disappointingly made only two league (Super Lig) appearances in the club’s 20 games, featuring as a substitute in losses against Faith Karagümrük (October) and Galatasary (January).

Atsu had grown out of favour. He was frustrated.

Before Hatayspor’s league game against Gaziantep, which was to take place on February 1, 2023, Atsu, according to Hatayspor administrative manager Fatih Ilek, approached his coach, Volkan Demirel, the young former Turkish goalkeeper.

Atsu wanted to take time off in order to find a new club.

Indeed, Ibrahim Sannie Daara, the former BBC journalist and Ghana Football Association communications director, recalls that Atsu texted him about wanting to leave Turkey. “He asked me if I had contacts in the UAE,” Daara, also a close friend of Atsu, said in an interview with TV3. “He wanted to move there.”

So, it was unsurprising when Atsu finally asked his coach: “Can I leave if I find a team?”

Demirel agreed, giving Atsu his blessings.

And so Christian Atsu went on to book a flight in advance. The plan was to, after Hatayspor’s next game against Kasimpasa, fly to Newcastle to spend time with his family before the search for a new club would begin.

The flight was scheduled for 11pm on Sunday February 5, 2023.

When that day came, Hatayspor welcomed Kasimpasa to their home for the league game.

Kick off was at 4pm local time, and Atsu was set to fly out seven hours later.

The match was competitive, both teams matching each other for most parts.

Then, in the second half, Volkan Demirel decided to make a substitution — one that proved to be vital.

He bizarrely brought on Christian Atsu. Bizarrely, because Atsu hardly played games at this club.

Perhaps it was Demirel’s goodbye gift?

It was to be the winger’s third game of the season; and his last.

The match raged on in cagey fashion — both sides were not ready to give in.

Then it reached the end of regulation time, the scoreboard reading 0–0.

It was time for the referee to rule on time added on.

So, how many minutes?

Seven, the fourth referee showed on his electronic board.

Game on. More time. More tension. The game remained tight.

Then, in the 97th minute, at the very death, Hatayspor were awarded a free kick.

Behind the ball, about 30 yards out, was Christian Atsu Twasam.

There is a comment under a Youtube video that shows Atsu’s last minute freekick against Kasimpasa.

The comment, clearly written with poignant emotion, and with the benefit of hindsight, reads: “Noo, please miss the FK (Free Kick), draw the game 0–0 and leave with your flight.”

As it turns out...

Well, read on.

So, where were we?

Right, Atsu, behind the freekick.

Fans were on tenterhooks. The stadium’s atmosphere was so tense you could cut it with a knife.

Atsu took a deep breath and made for the ball, with the goal in his cross hairs.

Bullseye.

The ball flew fast, taking a bounce in the six-yard box before beating Kasimpasa goalkeeper Erdem Canpolat.

The new Hatay Stadium, a 25,000-capacity ground, burst into a beanfest.

On the bench, there were fist pumps and festivity. On the pitch, there was a party. All around the stadium, there were deafening decibels of noise. There was delirium. There was delight.

Meanwhile, Atsu lay on the turf in total contentment, his teammates diving on to him to eventually create a pile of blissed out ballers. It was Hatayspor’s sixth win of the season, taking them just above the red, relegation zone.

With the last kick of the game, Atsu had scored his first and only goal for the club.

Little did he — and everyone else — know that that goal would be the final act of Atsu’s 13-year professional career. Little did all know that this was going to be the last time his cultured left foot would touch a football.

The last kick of that game would turn out to be his last kick in the beautiful game.

An anticlimax of the highest order.

In the dressing room, Atsu was mobbed by teammates as the after-party persisted.

They surrounded him, pulling his shirt, praising him. “Aaaatsu! Aaaatsu! Aaaatsu!” they chanted.

Later, Atsu danced pari passu with a teammate, showing the way with some rhythmic moves, which he probably borrowed from his one-time Black Stars teammate, the former captain Asamoah Gyan.

His flight was about five hours away, and he needed to prepare, but the mood was too good.

Why be a party pooper, he probably thought? Why not cancel the flight? Why not postpone going home? Why not stay and party away?

And so he did.

Much later, Atsu went back to the 9th floor of the Rönesans, where he lived.

He posted his goal across his social media platforms.

Later, his phone rang. It was his best friend, the Belgium-based Black Stars player Mubarak Wakaso.

Atsu and Wakaso, in terms of chemistry, were two peas in a pod. They would tease and taunt and troll each other, on the phone and over social media. They would regale each other regularly. “I really love that guy,” Atsu once claimed in an interview with GTV.

On this call, as usual, Wakaso was out to make fun of his friend.

“I’ve seen that you’ve posted your goal all over social media,” he said. “This fake goal you’ve scored, you’ve decided to worry us with it. You won’t allow us to rest!”

Atsu and Wakaso laughed about it, and laughed some more as they had a catch-up chat. After a while, Atsu, as he often did, told Wakaso he would call him back.

Hatayspor’s hero of the night decided to go to sleep, satisfied that he had had a good day, that he had also made the right decision to stay.

As Fatih Illek claimed, it was Atsu’s “happiest day” as a Hatayspor player.

Newcastle could wait, he must have thought. His family could deal with a little delay.

And so he closed his eyes, and all went dark, perhaps forever.

The next day, Monday February 6, 2023, turned out to be a fateful and fatal day.

At 4:17 am local time, it happened out of nowhere — the unthinkable, the unexpected, the deadliest natural disaster in modern Turkish history.

An earthquake, measuring 7.8 in magnitude, and lasting eighty seconds, exterminated almost everything.

In what was the deadliest tremor in the world since the one that occurred in January 2010 in Haiti, this fierce force shook Southern Turkey, and parts of Syria, violently, venting its spleen.

Regrettably, the Rönesans was reduced to rubble.

On Friday February 10, 2023, at the Istanbul Airport, Mehmet Yasar Coskun was accosted and arrested by Turkish police. He was later detained.

Coskun, per state news agency Anadolu, was trying to flee Turkey by flying to Montenegro.

According to the police, he was a culprit trying to escape the consequences of a catastrophic crime committed by him, in collaboration with a crust convulsion.

Coskun was a contractor.

A building contractor.

He claimed his trip had nothing to do with the earthquake — that crust convulsion earlier referred to — and that he was not fleeing as believed.

The police were having none of that.

Coskun was subsequently sent to the ‘Metris Prison’.

In 2013, an awesome apartment building rising up to 12 floors opened in Ekinci, a suburb of the Hatay Province city of Antakya.

The building was named Rönesans Residanz.

It featured four blocks of 249 luxurious apartments, a half-sized Olympic pool, jacuzzi, a gym, sports facilities, a children’s playground, two shops, a store, water falls, a walking and biking area, wake-up service and 24/7 security, among other enviable amenities.

It also had an indoor parking space which freed up a large area around the building “where all kinds of social activities can take place.”

It was advertised as “a Piece of Paradise”, “the most beautiful residence in the world”, attracting Antakya’s affluent class.

The building was believed to have met all the requirements of safety and legality. A year before construction was completed, permits for the building had been granted by the Ekincilar Belde Municipality.

Hatay Province mayor Lütfü Savas claimed that the building was put up properly and in accordance with regulations.

More importantly, like the famous Titanic ship, which was advertised as ‘sink-proof’, the brains behind Rönesans Residanz boasted of it being ‘earthquake-proof’. Afterall, the building was constructed on to a Floating Raft foundation, which ideally would protect it from seismic activity.

Basically, like the Titanic, ‘God himself could not sink” the Rönesans.

Well, as it turns out, God did.

The opening ceremony for the Rönesans was a landmark for the province of Hatay. It was the first of its kind in the province. The Hatay MP, the Governor and Mayor were all in attendance.

Subsequently, 700 people — other estimates say 1000 — moved in, some of whom thought the building was “an elite, safe space”. Among them were well-to-do sportsmen and officials, including players and management of the Antakya-based Turkish top-flight side Hatayspor.

The Rönesans was constructed by Antis Yapi, a reputable company with many decades of experience.

Mehmet Coskun, the contractor earlier arrested, was the chairman of the board and co-founder Antis Yapi.

Ten years later, and with the Rönesans in ruins in the wake of…

wait for it…

…an earthquake, Coskun was in custody.

In the aftermath of the ferocious February 6 earthquake, Turkey’s urbanization ministry estimated that over 84,700 buildings either collapsed or were damaged, contributing to over $100 billion worth of damages.

The Rönesans was one of them, dropping dramatically (or pushed to the ground, according to Geophysics professor Ahmet Ercan).

Strangely, all other older buildings surrounding it stood strong and statuesque.

Coskun would defend himself by saying the Rönesans was “solid”, with all the required licenses. But clearly, the building had not been on the qui vive for the disaster.

Sector officials claim that half of the 20 million buildings in Turkey fall short of building codes. Coskun was one of 246 suspects, including 27 contractors, detained by Turkish police after the earth quivered in a quake.

Coskun was accused, by residents at least, of using “cheap or unsuitable” materials to build the Rönesans.

Further faults were found by Japanese architect and engineer Yoshinori Moriwaki, who said the building lacked friction piles which could have prevented its collapse, as well as Ahmet Ercan, who opined that the building’s foundation was not as deep as it should have been (instead of about 10 meters, it went only three meters deep).

“Everyone who had a responsibility in constructing, inspecting and using the buildings is being evaluated,” said Turkish Justice Minister Bekir Bozdag.

In terms of accountability regarding the Rönesans, Coskun was not as lucky as the building’s Project Manager Ibrahim Dahiroglu and site manager Bayram Mansuroglu, who’ve gone off the radar of the police. Their locations are still unknown.

Like many of his contractor contemporaries, Coskun’s carelessness caused countless casualties. In the Rönesans alone, 800 people were estimated to have either been trapped or killed.

Among them was a beloved Ghanaian soccer superstar.

Back to Monday February 6.

Marie-Claire Rupio’s phone was buzzing. It was blowing up.

Atsu’s dear wife — “I just love her, that’s it!” he told TV3 — was receiving a lot of calls from his twin sister, Christiana, a nurse based in Accra. (The name Atsu is from the Ewe tribe, actually denoting that he is a twin).

Rupio finally picked up, “and that’s how I heard the news”, she told the BBC in an interview.

Later that day, that news spread all over the world: Christian Atsu Twasam was nowhere to be found following the Turkey tremblor.

Across Ghana, there was shock. Then panic. The earthquake gave Ghanaians heartache, especially as it left Atsu caged under the wreckage.

Among all the people in Turkey, why Atsu?

How?

What sort of eerily specific tragedy was this?

The Ghanaian population could not imagine the tribulation that the nation was to undergo: the anxiety for news, the prayers for the Atsu and the rescue crew, the sheer fear of you-know-what.

Then the next day, positive news came in.

Hatayspor President Mustafa Ozat announced that Atsu had been found. He had been pulled out of the rubble, sent to a hospital.

Relief.

But wait a minute. Which hospital?

There was a frantic search to find the hospital that was believed to be laboring to save Atsu’s life amidst potentially life-threatening injuries.

Ghana Ambassador to Turkey, Madam Francisca Ashietey-Odunton, said Ghana’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was “not sure yet which hospital or health facility Atsu had been sent to”.

Yie.

As it turned out, Mustafa Ozat had been misled.

The news was a hoax.

The next day, February 8, Hatayspor manager Volkan Demirel, who also lived in the Rönesans, and who in fact lost two of his neighbours, confirmed in an interview with Spor Arena that Atsu, along with the club’s Sporting Director Taner Savut, who was also ditched in the debris, were still missing. (Savut would later be found, identified and confirmed dead)

“If they were in the hospital, don’t you think I would share this?” Demirel questioned.

Nana Sechere, Atsu’s Ghanaian agent, who was on site, also cleared the air with some first-hand clarity. “Following yesterday’s update from the club that Christian had been pulled out alive, we are yet to confirm Christian’s whereabouts,” he announced.

So, false alarm?

Yes.

It was back to the worry. The hope. The Oh God, please.

Sechere tried to calm down worried Ghanaians: “We are doing everything we can to locate Christian,” he said. “As you can imagine, this continues to be a devastating time for his family.”

Six days later, on Valentine’s day, February 14, an uplifting update squeezed its way out of the rubble.

Two pairs of Atsu’s shoes were recovered.

Nana Sechere later revealed that he’d received confirmation that thermal imagery, through sight, smell and sound, was showing signs of up to five lives under the mountain of mess.

But…

“Unfortunately, we were not able to locate Christian,” Sechere admitted.

Sechere was worried. It’d been just over a week, and Atsu was still missing. In that time, many people had been miraculously pulled out of the Rönesans rubble.

A Hungarian rescue team recovered 12 survivors. A group of 75 Turkish coal miners rescued 40 survivors. It was said that Hungarian firefighter Lieutenant Colonel Dániel Mukics, part of a 55-person rescue team, recovered a female resident almost two days after the quake.

The Erzurum search and rescue team from the Erzurum Metropolitan Municipalities’ Fire Brigade Department also saved a 9-year-old boy from the wreckage.

Indeed, the rescue and relief effort of the Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management consisted of a 60,000 search-and-rescue force, 30,000 volunteers and 5000 health workers. When Turkey called out internationally, 141,000 people poured into the country to help.

Yet at the Rönesans, rescue efforts, at least as far as Atsu’s family and countrymen were concerned, were not being as effective as expected.

“Things are moving incredibly slow, and as a result of that, many rescues are being delayed,” Nana Sechere said in impatience. “Lives are being lost due to a lack of resources available to workers.”

“The time is running,” Marie-Claire Rupio told the BBC.

It really was.

This was on February 10 — four days earlier, and four days into Atsu’s disappearance.

“We have seen some dramatic rescues; people still being pulled out of the rubble. Does that give you some hope?” the host of the interview asked Rupio.

“A bit, yeah,” Rupio said uninspiringly, her countenance downcast. “I still pray and believe he is alive.”

Meanwhile, under the rubble, was Atsu still alive?

No one could tell, but it was likely that he was.

Well, looking at things from the day Rupio granted her BBC interview — four days in — there was hope.

Why?

The longest known time anyone had stayed under rubble before rescue was 94 hours — four days.

That’s why.

This was the story a 17-year-old boy in Gaziantep, who became the collective relief of search and rescue efforts.

The young boy, Adnan Muhammed Korkut, lived on the 5th floor of an eight-storey apartment building that tumbled down. When he stabilized after treatment, he confessed to surviving by eating flowers.

Now, let’s look at Atsu’s chances from February 14 — eight days in. This was when two pairs of his shoes were found, fueling the feeling that there was hope after all, providing fillip to the faith that he may still be breathing in there.

So, was he still alive at this point?

Well, even by the standard of the miraculous rescues, he was most likely not.

And, who is to say that he didn’t die immediately after the Rönesans fell to its knees?

That, given what we know now, would have been better, wouldn’t it?

It would have been bearable.

But, if Atsu were alive, even after four days, my God, it must have been gut-wrenching for him.

It must have been so cruel. Dark. Suffocating. Excruciating.

Imagine being confined under a pile of concrete as you grow weak, gasping for air, a claustrophobic person’s worst nightmare. He had no water, no food — and he was most likely gone for good.

Nonetheless, in Ghana, across every nook and cranny, across churches and mosques, citizens prayed profusely.

“We pray that our fellow Ghanaian, Christian Atsu, is found safe and sound,” said Ghana president Nana Akufo-Addo.

“Let us continue to pray for our brother Christian Atsu,” added former Ghana president John Mahama.

Over in the UK, congregants of the Hillsong Church, located a mile away from St James’ Park, and where Atsu used to fellowship during his five-season stay at Newcastle, prayed earnestly for their faithful fellow worshiper.

All around the world, admirers and sympathizers alike waited with bated breath.

“They say when death has its grip on something, life cannot snatch it,” — Ashanti Proverb.

On Saturday February 18, twelve days after the earthquake, after almost two weeks of anxiety and “emotional torture” (as the Ghana Football Association described it), it all came to an end.

The worry, the wait, all taxied to a solemn stop.

It was confirmed.

Though it was ubiquitously suspected, all but known, it was still painful when it was pronounced.

At 6 am Turkish time, Christian Atsu Twasam was pulled out of the rubble — dead.

Nana Sechere, the agent, Christiana, the twin, and one of Atsu’s brothers, were at the scene, setting their eyes on the body, barely believing that their once lively brother was now lifeless.

“It is with the heaviest of hearts that I have to announce to all well-wishers that sadly, Christian Atsu’s body was recovered this morning,” Nana Sechere said. “My deepest condolences go to his family and loved ones. I would like to thank everyone for their prayers and support.”

At the age of 31, Atsu had bowed out of this unfair labyrinth of the unknown called life.

The ruthless earthquake had affected 14 million people in Turkey, about 16% of the country’s population.

Over 46,000 people had died, with close to 115,000 injured.

Among these, there had to be Christian Atsu — a random occurrence that the Ghanaian football fandom could hardly fathom.

Study his story carefully, and you would find out that it was clear that death had trained its icy hands on Atsu right from the start.

It was almost inevitable, because there were just too many “if onlys”, way too many “what ifs”.

Death, indeed, had gripped him — and as the Ashantis conclude confidently, life had failed to snatch him.

Across the world, there were tears and tributes. There were eulogies, too, expressed with profound gestures.

A minute of silence was observed across many matches, especially in the Premier league, where Atsu had been affiliated with as many as four clubs.

At St James’ Park, where Newcastle was set to play Liverpool, there was emphatic empathy and emotion. From the scoreboard, Atsu smiled, his image in black and white, his years of life written at the bottom: 1992 to 2023.

Across the stadium, there was a touching tribute — a minute’s silence, followed by a prolonged standing ovation from everyone: all 22 players and three referees gathered by the center circle on the pitch, the close to 52,000 fans in the stands, the coaches and substitutes on the bench.

Liverpool fans sang their “You’ll Never Walk Alone” anthem, and Newcastle fans added their voices too.

Over in the VIP box, Atsu’s family — wife and two sons (without the very young daughter) — participated in the applause.

Marie-Claire Rupio, in an all-black apparel, patted her boys — 10-year-old Joshua and seven-year-old Godwin — as they clapped, clad in Newcastle jerseys.

The widow and her boys felt the warmth. They knew the city of Newcastle upon Tyne was never going to let them walk alone.

At 7:25 pm Ghana time on Sunday February 19, Christian Atsu Twasam returned home, from Turkey with tragedy.

The return of his body, via a Turkish Airlines cargo plane, was a national event, broadcast live on TV and radio.

On the tarmac in front of the Kotoka International Airport’s VIP section, there were people from all sections of society: politicians, press, police, pastors; family, friends, fans — all mourners, despite their varied roles.

More importantly, there was the Ghana Armed Forces, who provided pallbearers to carry Atsu’s Ghana flag-draped coffin to the morgue of the 37 Military Hospital.

Ghana’s president, His Excellency Nana Akufo-Addo, was represented at the airport by his vice, Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia.

“It is a painful loss,” the Veep said, “a very painful one.”

“We hoped against hope with every day that passed,” he added, “we prayed and prayed, but alas, when he was found, he was no more.”

There were times during Atsu’s stint at FC Porto, his first professional club in Europe, when during lunch sessions at Hotel Solverde, he would consume his chicken right to the bone, even going beyond.

His teammates would laugh at him, calling him “hungry Atsu”.

As later recounted by his teammate then, Danilo, Atsu apparently ravenously rammed every bit of his food into his mouth in remembrance of his rough upbringing.

Atsu, ever light-hearted, ever smiling, and never one to take things personally, explained to his teammates why he did that.

Right from childhood, he said, he learnt not to waste food, given the fact that he didn’t know when the next meal would arrive, where the next meal would come from.

“What a punch in the stomach,” Danilo recalled. “If that’s worth the pun.”

In March 2018, before the ‘Black Star Gala’ that was to raise funds for Atsu’s collaboration with AATC to build a school in Ghana, Atsu met the press to promote the event.

At that presser, Atsu was asked why he seemed to put his heart and soul into charity work.

Why did he care so much?

“Why?” he asked rhetorically. “I want to show love to the kids. I had a difficult childhood. I will not allow these kids to go through the same situation I went through.”

While recounting this ‘difficult childhood’, Atsu broke down in front of reporters. He could not hold back the tears as he narrated the story of who he was and where he’d come from.

“Remembering can be a source of both hurt and inspiration,” wrote the Northern Echo’s Scott Wilson. “In Atsu’s case, the pair go hand in hand.”

Christian Atsu was born in Ada Foah, a serene coastal village in South eastern Ghana, known for its palm-decorated beachfront, and known for being where the Volta River pours into the Atlantic Ocean.

He was the youngest of 11 children.

At seven years old, he and his twin sister Christiana made the two-and-a-half hour journey to Accra, upon the invitation of an elder brother of theirs, who had earlier moved to the capital to work for some capital.

The twins’ purpose for migrating to Accra was to attend school.

With his brother, the twins lived in what Ghanaians call a “chamber and hall” — a single bedroom with a living room, complemented by a washroom. This was in the Accra suburb of Madina.

Later, their mother and two of their elder sisters joined.

All six of them shared the small, simple space.

Atsu’s brother, inevitably, began to suffer under the weight of winning bread for his family.

Eventually, he struggled to pay their rent, and the family was thrown out.

“It was hard,” Atsu recalled. “It was too hard.”

The family moved into an uncompleted building to settle, in a popular arrangement where landlords normally give out spaces in their yet-to-be-completed houses for impoverished families to sojourn.

From that building, Atsu would head off to the streets, sometimes staying away from home for as long as two weeks. Mission? To make ends meet.

He was too young, around 12, yet there was no option than to delve into hustling. “I said to myself, I’m not going to stay here anymore,” Atsu recalled. He said he did that to “forget things”; among others the haunting hardship at home.

Away from home, he lived on the streets with his friends, fellow pre-teens, doing everything possible — including selling items like rubber bags in traffic and at Madina market — to earn something for himself and for his family, who struggled to pay his school fees.

“I had to work hard to feed my family,” he remembered, “I could not bear to see them suffering, especially my twin sister and mother.”

Of the streets, Atsu would later recall: “I saw child labour; I saw child poverty.”

His mother, Afiko, eventually moved back to the village after some time selling at Madina market. “It was difficult when she went back,” Atsu said.

His other siblings would follow.

Atsu’s infatuation with football was forged on the streets of Madina, where as a seven-year-old boy, he started playing barefoot.

He went on to play for an Accra Under-12 side, where he got to wear boots — a pair of Puma boots — for the first time.

In 2004, aged 12, a breakthrough came for Atsu when the Ghanaian academy of Dutch club Feyernoord discovered him while he was playing for colts (youth) club Peace FC, at an Accra Regional football tournament.

Feyenoord Academy (now known as West Africa Football Academy — WAFA), was based in Gomoa Fetteh, in Ghana’s Central Region, a two-hour drive from Accra. They incorporated Atsu into their youth set-up, the Under-14 side.

This gave Atsu an opportunity to survive, to become his family’s hope. He was clothed, fed, sheltered and educated, all in an enabling environment that was to groom him into a bright future.

He grew under the guidance of the legendary coach Sam Arday, the “multi-system man”, who led Ghana to Africa’s first football Olympic medal (bronze) at the Barcelona Games in 1992, and who won the 1995 FIFA Under-17 World Cup. “Feyenoord polished my talent,” Atsu said, “It was where I learnt when to pass, when to tackle, when to dribble and so on.”

Dominic Adiyiah, who would become a world Under-20 Championship winner with Ghana in 2009, securing the tournament’s Golden Shoe and Golden Ball, was Atsu’s senior at Feyenoord.

Atsu made an impression at Feyenoord with his precocious talent. There was one time, while he was still an Under-14 player, when the senior team of the Academy played against Ghana’s national Under-20 football team, the Black Satellites.

Coach Sam Arday placed Atsu on the bench.

In the second half, while the score was 1–0 in favour of their opponents, Arday threw on 12-year-old Atsu, who ended up scoring an equalizer, despite playing against bigger and older boys.

That same year, Atsu was in the middle of a six-month training camp with Feyenoord when he heard that his father had succumbed to sickness. His brothers initially kept the news away from him, because they knew how much he loved his father, and thus did not want it to disturb his focus at Feyenoord.

Atsu’s father — unlike his mother, who was more interested in Atsu going to school — fully supported Atsu’s football aspirations. He held a special place in Atsu’s heart. “My dad wanted me to play football,” he once said in an interview with ETV. “He pushed me to play. He encouraged me. ‘My son, you have talent’, he would say.”

Atsu admitted later that he did not ask, and thus didn’t know, what his father’s sickness was. “But I knew he was drinking a lot of alcohol,” he told the Daily Mail.

A few weeks after he got sick, Immanuel Twasam, a farmer and fisherman among other fields, died. Rather than peacefully, he died painfully and pennilessly.

Atsu’s brothers called to break the unfortunate news to him.

“What happened?!” young Atsu asked them. “Didn’t you take him to the hospital?”

That was when the heartbreaking answer came: they didn’t have money to send their father to the hospital.

Atsu, who was not being paid at Feyenoord, could not extend a helping hand too.

It hurt.

His poor old man had perished because he was poor.

“I don’t want this to happen to anybody — suffering because of money,” Atsu would later say, amidst sobs, many years later. “It is not right.”

His mother now faced the daunting duty of raising Atsu and his 10 siblings on her own. On the meagre money made from market selling, she was set to seriously struggle.

Atsu would many years later tell the Daily Mail’s Craig Hope that his father’s death proved pivotal; it was when he vowed to become either a medical doctor — to help the sick — or a professional footballer, to propel his family out of penury.

He became the latter.

In January 2010, a few days after his 18th birthday, Christian Atsu found himself on an airplane for the first time in his life.

He was at the Kotoka International Airport, on his way to becoming a professional footballer.

Finally, a chance to earn and fend for his family.

He was excited. He was hopeful.

From the plane, he sent a text to Abdul Hayye Yartey.

Who was Yartey?

He was the man who scouted Atsu into the fold of his club, Kasoa-based Cheetah FC.

Atsu had earlier left Feyenoord abruptly — after his third year of junior high (the highest level at Feyenoord) — because his mother insisted on him quitting and going back home to concentrate solely on school.

After leaving Feyenoord, Atsu then started the first year of senior high, attending from home.

But football would never die as Atsu’s destiny, and Mama Afiko could do little about it, eventually at least.

While in senior high, Atsu kept cheating on school with Cheetah FC, his first proper senior level football club.

He continued his development at Cheetah for about three more years, during which time he was married to football, keeping school as a ‘side chick’.

Cheetah did not have the fancy facilities Feyenoord had, but Atsu, as he later said in an interview, didn’t see the need to “look back”.

By 2010, school was out of the way, and fortuitously, Atsu had caught the eye of a Cheetah FC-affiliated Canadian football agent based in Portugal.

Thanks to this agent, and to Yartey, who facilitated it all, Atsu was on his way to Portuguese giants FC Porto for trials.

“Mr Yartey, I really appreciate you,” Atsu wrote in the text. “I’m not going to return. I’m going to succeed on this trial.”

Yartey, who says he cried “like a baby” upon receiving the news of Atsu’s death, remembers Atsu further promising him that he would make him proud, that he was going to play football to the highest level.

“I won’t ever discover a talent like Atsu again,” Yartey would later say, emotionally.

At Porto, teenaged Atsu had to quickly adapt to Portuguese culture, food, football, language, people and weather.

But with football, he dived straight in with no difficulties, swimming with style and speed.

After just three days training with the club’s junior side, he impressed, and was offered a six-month contract.

He played in the junior team, and after what proved to be an injury-hampered first few months, he recovered to help the team win the Portuguese youth league, bagging the Most Valuable Player honour along the way.

In the 2011/12 season, he spent a year on loan at fellow Portuguese side Rio Ave, where he impressed, coming back ready to join Porto’s senior team. Atsu was part of Porto’s Portuguese Primera league-winning team for the 2012/13 season, playing 17 games.

His performances eventually caught the eye of English Premier league giants Chelsea, who doled out 3.5 million pounds to sign him.

Atsu would barely play a game for Chelsea, going, as was typical of Chelsea’s transfer policy then, on loan to five different clubs in four years, between 2013 and 2016. There was Vitesse (Netherlands), Everton and Bournemouth (England), Malaga (Spain) and Newcastle (back in England).

Those years dealt Atsu a lot of drain and strain. “I know it’s my job, but it’s difficult moving all the time,” he once told The Mirror. “It’s really difficult because every season you are having to move your things and your family into a new place, meeting new people again and so on.”

In 2016, at Newcastle, he would finally settle, completing a 6.5-million-pound move from Chelsea after his loan stint.

At Newcastle, Atsu and his family found a home. He spent five seasons with the Magpies, becoming a cult hero, even inspiring the composition of a chant:

“Oh Christian Atsu, he is so wonderful,

When he scores a goal, oh it’s beautiful,

Magical,

When he runs down the wing,

He’s fast as lightning,

It’s frightening,

And he makes all the boys sing!”

In April 2012, James Kwasi Appiah, a former captain of Asante Kotoko and the Black Stars, was named coach of the latter.

A 1982 Afcon winner with Ghana, and a 1983 Africa Cup winner with Kotoko, Appiah had succeeded Serbian Goran Stevanovic.

Appiah — Ghana’s first local coach in 10 years — immediately went to work in scouting new players, an activity which would later become known as his forte.

A friend of Appiah’s in London tipped him off about a budding talent playing in Portugal.

Appiah followed up, checking out this highly-recommended, highly-rated talent called Christian Atsu.

After watching “four or five matches”, the coach was convinced.

Later, Appiah would call up Atsu and tell him: “I have handed you the call-up, but the rest is up to you. You need to prove to Ghanaians that you deserve to be in the national team.”

On June 1, 2012, the Kwasi Appiah reign began with a game against Lesotho; a 2014 World Cup qualifier.

Ghana completely ate the lunch of the Southern African nation, scoring seven unanswered goals.

Christian Atsu, making his debut aged 20 — “a dream come true” he admitted — scored a goal in what was a man-of-the-match display.

After the game, the BBC described him as an “excellent prospect”, while ESPN thought he was “quick and technically impressive”.

Atsu would go on to play at the 2013 Afcon, the 2014 World Cup, as well as the 2015, 2017 and 2019 Afcons.

His national team acme came in the 2015 Afcon in Equatorial Guinea, when he spearheaded Ghana to the final, where the four-time African champions almost ended a 33-year-wait for the trophy. They lost narrowly to Ivory Coast on penalties.

Atsu, despite missing out on the trophy, was named Player of the Tournament, immediately attaining stardom across the continent.

Years later, President Akufo-Addo, in appreciating Atsu’s contribution to the success story of the national team, said Atsu was an “exceptional athlete”.

He was indeed an exceptional athlete.

Atsu was a footballer who was not only a consummate professional, but one with towering talent.

When he sauntered on to the scene for the Black Stars 11 years ago, Ghanaians were awestruck by his athletic abilities, his aesthetic qualities.

His left foot had a lustrous love affair with the ball; his deeds with his feet were deft, dexterous and ambitious; he played with freedom and flair; he was fast and frightening.

At 5ft 8 inches, Atsu wasn’t exactly tall, but that wasn’t a flaw, because it made him light and quick. “I know I’m very small,” he said, “but I have a very big heart.”

Atsu was an excellent dribbler — his gift was nifty, fine footwork. That, coupled with him being an ace of pace, one who could race in space, resulted in him being hailed as “Ghana Messi”.

“I love Messi,” Atsu himself once admitted. “I love his style of play; he can dribble two, three, four players at a time. And, aside football, he is a very humble guy.”

Veteran Ghanaian sports broadcaster Karl Tufuoh opined that Atsu was “the most gifted Ghanaian footballer since Abedi Pele”.

Coincidentally, Atsu considered Abedi Pele — the three-time African Footballer of the Year — as his favourite all-time Ghanaian footballer.

“I never thought I’d reach this level,” Atsu confessed of his rise, and of the comparisons with great footballers.

“I love football,” he added, “I really do love football.”

Atsu believed his talent was God-given.

“It’s all by the grace of God,” he told ETV. “I always say by ‘God’s grace’ because there are some people who are very good in football, but without the grace of God, they are not able to get to where they have to be.”

Once upon a time, Christian Atsu, while in camp with the Black Stars in Cape Coast, saw a little girl carrying goods on her head.

The girl looked weary, from hawking and talking and walking over long distances, all while trying to earn pittance that was perhaps not even going to be enough to put food on her table.

Atsu was moved. He had once been in her shoes, back in his days suffering on the streets of Madina.

“How much does all that you are carrying on your head cost?” he asked the girl.

Without waiting for an answer, Atsu reached for a small bag he usually carried with him.

“I saw him pull something out,” remembered Ibrahim Sannie Daara, who, as the Ghana Football Association’s Communications Director then, was the only witness that day.

That something was money.

Atsu told the girl: “Give the money to your mum. Tell her to send you to school.”

Moments later, Atsu wept.

“It really touched me,” Daara said. “He told me not to tell anyone about what I’d seen.”

“I feel so sad to see humans suffering,” — Christian Atsu Twasam.

Christian Atsu, as his club Hatayspor once described him, was a “beautiful person", not least in terms of his character.

“He was a beautiful, lovely soul,” said Arms Around the Child’s Ellie Milner.

This was a man who gave his all: to God, and especially to man. When he saw people suffering, he felt sad. He felt bad.

He was a helper. He was hope. He was human.

He was honest, too. Humble.

“He was an angel on earth,” said Hayye Yartey.

“He was a nice, nice, special person,” said Rafael Benitez, Atsu’s coach at Newcastle.

“I have never seen a guy like that,” said Newcastle talisman Allan Saint Maximin. “He was very nice and kind.”

“He was always trying to help the poor,” said former Ghana coach Kwesi Appiah.

As a person, Atsu was soft-spoken and bashful, and only found his eloquence in the beautiful act of benevolence. He was a phenomenon of philanthropy, a saint of sacrifice.

To those in the darkness of despair, he was their light; for those who languished in anguish, he showed love. He was compassionate, passionate about punishing poverty, about propagating prosperity among the poor.

“I am one of the lucky people God has blessed,” he told the Guardian. “I’m very lucky and privileged to be in this position. I had nothing, and now I’ve got so much, so I have to give something back.”

The Daily Mail’s Craig hope made an interesting observation about Atsu’s determination to use his success to help others. “He left me with the overriding impression that his talent was not a gift to football, or to himself, but a means of helping others.”

In the wake of his death, many people popped up on social media to share stories of how Atsu helped them in various ways, out of nowhere, all on the quiet.

“Football changed my life completely,” Atsu said. “Sometimes what’s happened seems like a miracle, but it’s enabled me to help my community and family.”

Apart from Arms Around the Child, Atsu also did charity work with an NGO called Crime Check Foundation, which, among others, specialises in issues of prisoners.

Atsu had been monitoring the foundation for a while, and later reached out to them. Typical of his ready-to-help nature, Atsu didn’t have to be asked before he extended a helping hand.

Atsu pumped money into the foundation’s many projects. Under their ‘Petty Offenders’ Project’, he funded the fines of a plethora of petty offenders — over 150 of them — and helped in reintegrating them back into society by providing capital for them to trade.

Under their “Health Check Series”, Atsu paid the medical bills, including that of surgeries, of many individuals who weren’t prisoners.

Under their “General Charity Series”, Atsu provided capital for poor petty traders, widows and orphans.

And under their “Education Support Series”, he paid the school fees of many students across Ghana.

In addition, Atsu consistently advocated for the Non-Custodial Sentencing Bill — a bill that would prevent petty offenders from being unfairly imprisoned and being mixed with hardened criminals. The bill has been stuck in Ghana’s parliament for many years, and through Atsu’s advocacy, it is likely to become law soon.

“He did a lot,” said Ibrahim Kwarteng, Crime Check’s chief executive, whom Atsu extended personal financial help to when he lost his wife. “We have lost a monumental figure.”

Atsu — who was also a donor to UNHCR’s ‘Face to Face’ fundraising in Ghana — will not see his philanthropic efforts be in vain, or go down the drain, even after his death.

The school he started building in collaboration with AATC at Senya Bereku, 84km west of Accra, will be completed.

Fans of Newcastle United have started a fundraiser to that effect.

“We will still build the school somehow,” Ellie Milner said a determined manner during an interview with Citi TV.

A ceremony was recently organized to mark one week after the return of Atsu’s mortal remains to Ghana.

It happened on the Adjiringano Astro Turf, not far at all from Atsu’s family house at Ogbojo, where a book of condolence had been opened for many famous and regular visitors to sign.

At that ceremony, the VIP tent, which featured dignitaries like family elders, government officials, former footballers and prominent administrators, had inscribed on its panel: YOUR LEGACY LIVES ON.

That school in Senya Bereku;

all the destitute men and women he heartwarmingly touched;

all the prisoners he helped release;

all the sick he helped heal;

people from all walks of life whose hearts and minds are filled with Atsu-inspired gratitude;

and all the encouraging efforts that made him an iconic symbol of selflessness, have collectively forged a lasting legacy that will breathe for ages to come, passed on from generation to generation.

That legacy, like his Lord Jesus Christ, will live on forever.

Epilogue

Ah, speaking of Jesus Christ.

Atsu’s knack for helping others was also inspired by his Christian faith, which he wore on his sleeve.

Atsu put the “Christ” in Christian.

“Christian Atsu could not have had a more appropriate name,” wrote the Guardian’s Louise Taylor. “He was a Christian in every sense of the word.”

“Christian,” said Yartey. “He was truly a Christian.”

Yartey remembers how Atsu, when he went to Porto, donated his first salary of 800 Euros to a church.

“My faith is the most important thing in my life,” Atsu would admit to the Guardian.

Atsu always believed that his journey in football, his destiny in life, was determined by the design of the Deity that is God Almighty.

He believed that everything that had happened, that was happening, and that would happen, was all, through God, working for his good.

“And we know that God causes all things to work for the good of those who love Him, and to those who are called according to His purpose,” he told ETV.

“So if you follow God,” he added, “I believe everything will be fine.”

There is a video, filmed by FIFA TV during one of the Black Stars’ camping sessions, where Atsu is seen singing a soulful Christian song, one that summed up his faith.

“I am yours, my Lord Jesus,

“Always and forever, I am yours,

“My heart sings: glory be to your name.”

Indeed: to God be the glory for a life well lived.

Christian Atsu Twasam is gone, but the hearts of many, he won.