“Where is Chris Briandt?”: The sad tale of a man who turned down greatness

Chris Briandt — does the name ring a bell to you as a Ghanaian football fan? Of course it doesn’t. But it should — and here’s Fiifi Anaman to tell you why

At the Accra Airport sometime in March 1958, Chris Briandt waited for his flight to Germany.

He was seated by his wife, Wilhelmina, and his daughter. Ahead of him was an opportunity of a lifetime, yet the captain of Ghana’s national football team didn’t seem excited about it. He looked pensive. He seemed unhappy.

The Ghana government had offered him a scholarship to study football coaching at the Cologne Sports Academy. It was a package that meant travelling abroad and becoming a ‘been-to’, a priced aspiration of most Ghanaians of that era, yet Briandt didn’t want it.

Perhaps it was because it ultimately meant leaving his family behind.

“Briandt never wanted to go,” says his friend, N.A Adjin Tetteh, 58 years on.

Why not?

“Perhaps it dawned on him,” Tetteh speculates, gravely.

It?

What was it?

Briandt himself didn’t even know what it was. All that he was sure of — and it weighed heavily and worryingly on him — was that it was an ominous inkling.

Something just didn’t feel right.

But he could not act on it. National duty called, and he could not say no, because he knew what the consequences would be: horrid hostility, from the government and from the public — haunting, daunting, definitely not something anyone would want.

Ghana in the 1950s was a state immersed in a culture of deep patriotism, largely fuelled by the passionate struggle for independence, and so the mood was sensitive to civic disobedience. Declining to serve the country was sure to give people enough reason to charge him with treason. The 29-year-old knew he would be vilified and crucified, never to be forgiven.

After a meeting with Henry Plange Nyemetei, Briandt decided to swallow his reservations, to wallow in his discomfort. H.P Nyemetei was the President of Hearts of Oak, the club Briandt had spent his whole senior career since joining as a teenager in 1949.

“It was HP who managed to convince Briandt to go,” Tetteh says. “He told him, ‘Look, you must go. You must serve your country.’”.

Indeed, despite his status as a public figure always threatening his privacy, Briandt, who seemed allergic to the tension of attention, somehow managed to remain perpetually insular.

He was a private man, a lover of the quiet life. “He disliked being on radio and in the newspapers,” recounts Dogo Moro, Ghana’s dominant international defender from the late 50s to the early 60s who came a generation after Briandt.

Briandt wanted to keep his life simple. Sane and plain. He was barely visible off the pitch, always tucked away in reticence, choosing anonymity over vanity.

Moro recalls that the only times anyone would see Briandt was during training or a match. Aside from that, he was either at his office at Kingsway Stores — where he occupied a top management position — or at home with his family.

“Briandt was someone who didn’t like to involve himself with many things,” says his friend and national teammate, James Adjaye. “He always loved to be in his own small and quiet corner.”

This reserved nature made him a man very much in touch with his family, and this made saying goodbye to them difficult.

He wished he wasn’t leaving them. He wished he had a say. That he could have his way. That he could stay.

But he had made a commitment. There was no turning back

When Hearts of Oak held a well-attended farewell party for him, the tributes were touching. Their coach, the Englishman Ken Harrison, called Briandt “Ghana’s greatest ever captain.”

Harrison wasn’t being hyperbolic. Briandt being a class act as a leader was an assertion that was unanimously embraced as a fact during the 1950s. He had been Ghana’s captain for eight solid years — a spell that remains the lengthiest of any captain to date.

On the pitch, he was the face of grace, a sportsman of substance, fearless and peerless. In 1956, he was named Sportsman of the Year, a rare feat for a defender. In 1959, Sir Stanley Matthews, the English football legend and winner of the first Ballon d’Or, wrote that Briandt was the “greatest footballer and finest sportsman” he met on his West African tour of 1957.

“Briandt was highly respected,” Tetteh says, taking his time to stress on ‘highly’.

According to Tetteh, the 1950s saw three footballers reign supreme in the country, the primus inter pares among a sizeable line-up of national stars: James Adjaye, Charles Gyamfi and Chris Briandt.

Kofi Badu, widely regarded as Ghana’s finest ever sportswriter, agreed with this opinion in an October 1955 column for the Daily Graphic. “I never saw anyone to equal the wizardry of James Adjaye, nobody with the ball killing of Charles Gyamfi, and no full back with the flair and enchanting qualities of our skipper, Chris Briandt.”

That Briandt — a defender — was on this venerable list was telling.

Emmanuel Christian Briandt was born on the fifth of July 1929.

He was born in Accra, the capital of the Gold Coast, as pre-independent Ghana was known as. He was the third of the seven children produced by Stephen Julius Briandt and Felicia Ayorkor Briandt, a Ga couple.

Briandt had his education at the Government Junior Boys’ School from 1936 to 1940, and the Kinbu Government Senior Boys’ School from then till 1945. While a student, he discovered an ardent interest in football, and proved to have the talent to boot.

He shone as a young star, playing and excelling in many interschool competitions. Academically, he was on top of his game too. “He was brilliant,” Tetteh says. “In fact, many believed one of the factors that led to him getting the Gold Coast XI captaincy was because he was well-schooled and more clever than most,” Moro reveals.

After his education, Briandt, like every footballer of that era, worked while he played football, because the sport, up until 1992, was organized under strict amateur rules. He taught at the Osu Christiansburg Progress School while he played for Osu Diegos and, later, Accra Rolands — the nursery team of Hearts of Oak.

Young and curious, he discovered an interest in Horse Racing during these years, becoming a jockey at the Accra Turf Club. His devotion saw him subsequently master the sport so much that he started to give accurate predictions of races.

This ability earned him popularity and favour among punters, most of whom were British, members of Accra’s affluent class who worked at wealthy companies such as the United African Company (UAC), a vast, British-owned commercial conglomerate.

In January 1949, one of the punters offered Briandt a job at the UAC. He started out as a salesman with its flagship unit Kingsway Stores. He would rise through the ranks to become a manager at Kingsway, the same stores where he met his wife Wilhelmina.

That same year (1949), Hearts of Oak snapped him up, signalling the beginning of what would turn out to be a storied career.

As a footballer, there is a reason why Briandt commanded such reverence.

On the pitch, he was unconventional in his ways, disconnected from the predominant norms for his kind.

While defenders sought validation by being bestial, Briandt seemed to be special. He preferred his aggression average and not savage, his game based on brain rather than brawn. He was the type to disarm you rather than harm you, the type to steal the ball rather than to make you fall, the type whose temper was under control while on defensive patrol, the type who chose intelligence over belligerence.

Briandt was refined: He belonged to the gentry of football sentries. In his book “The Glory Days — The Soccer Legends of Ghana’s Gold Coast”, author Alex Ayim Ohene wrote that Briandt was “easily one of the most cultured central defenders to have graced the football field.”

Look through the sports pages of the 1950s and you would often find Kofi Badu using the expression “icy cool” to describe Briandt’s disposition towards the opposition.

“He was absolutely calm,” Tetteh agrees. “He could make tackles in the box against very tricky players that were timed with utmost precision,” wrote Ayim Ohene.

This calmness and caution was what Daily Graphic writer Charles Nartey described as “polished”, and why “he just could not be beaten.”

Nartey was observing Briandt as he played in two games for an Accra team against a Lome team in August and September 1953.

“By jove, he was as as constant as day and as strong as the rock of Gibraltar,” Nartey wrote. “No ball could slip past him, no forward was too smart for him, and no number of attackers could overwhelm his stand.”

Briandt himself once explained that his composed nature was born out of a desire to keep a clean disciplinary record. “I tried as much as possible not to violate the rules,” he said.

Indeed, this attribute gave him a unique edge over his coevals. Of the gallant defensive barricades that the Gold Coast produced in the ‘50s decade — among them Samuel Ashison, Okoe Addy, Kwame Appiah and Ben Koufie — Briandt was the giant that stood out, the Burj Khalifa of this skyline of talent.

“You could hardly beat him at the back,” Tetteh says. “He was a marvellous header of the ball too, and would score many goals with his head.”

“He used his height advantage a lot and was unbeatable in the air,” Adjaye adds.

“His defending was such a sight to behold,” narrates Moro, who says he idolized the captain. “It was beautiful. Everyone respected him. He was the standard we all referred to. He wasn’t rowdy at all, always cool on the ball.”

“As a young defender, it was one of my biggest wishes to play alongside Chris Briandt,” Moro continues. “Although I was unlucky because I came in when he’d left for Germany. I used to think, ‘Man, if I could play like this man, that’d be it for me!’ He was a proper defender.”

And he was a proper human too. Briandt, supremely scient on the pitch and ever riant off it, was loved as much for his light style on the pitch as he was for his bright smile off it.

Light skinned and well-trimmed, he was a fine-looking man who “even a man would admit was very handsome”, Moro says.

Briandt had a pleasant personality, his radiance almost approaching a fault. “He was always smiling,” Tetteh says. “Those who knew him well will never forget the warmth of his nature,” Ohene wrote.

Soft spoken, well-mannered, well-dressed, well-to-do: Briandt was a gentleman, through and through. His nickname? Gentleman Player.

“Oh, what a gentleman!” Moro says, the admiration palpable. “If you ever saw Chris Briandt in his neat suit and tie in his office at Kingsway Stores, you’d know what gentlemanliness meant.”

“Some of us young players would go to his office just to catch a glimpse of him, and he’d give us gifts. We often wondered why he bothered himself to play football, with all of its physicality, politics and dirt.”

“He was a perfect gentleman,” Tetteh says, his tone sober, as he stares at the ground, shaking his head in a trance.

“Perfect,” he adds.

Adjaye can’t agree more. “Chris was a gentleman,” he says. “He was such a calm fellow. You’d never see him fight anyone.”

After Ghana attained independence in 1957, Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah began to send his trusted associates — or his “boys”, as Tetteh calls them — around the world to seek some milk to feed the growth of new born baby Ghana.

Kojo Botsio, who had become friends with Nkrumah as students during the 1940s in the United Kingdom, was one of them.

As Minister of Foreign Affairs, and he was deployed to West Germany to solicit some support in relation to the development of Ghana sports.

Botsio managed to return to Ghana with four scholarships from the West German government, intended to facilitate the coaching training of exceptional personalities within two of Ghana’s biggest sports, football and athletics.

Four men were chosen: Emmanuel Christian Briandt and James Kenneth Adjaye from football, Nii Ayikai Adjin Tetteh and John Asare Antwi for athletics.

Tetteh and Antwi had been moguls in the business of speed in their hey days: the former had been a national record holder in 60, 100 and 220 yards, while the latter had been a national half mile champion.

As far as football was concerned, Briandt was in good company.

James Adjaye was Ghana’s first big football showman — what people of his era called a ‘crowd puller’. He was an entertainer, a master of skill and thrill.

Before there was Abedi Pele, before there was Mohammed Polo and Opoku Nti, before there was Abdul Razak and Osei Kofi, and before there was Edward Aggrey-Fynn and Baba Yara, there was James Adjaye, the Generalissimo of these Field Marshals of playmaking, the High Priest of the faith of dribbling.

“James Adjaye could play football better than everybody!” Dogo Moro says, almost aggressively, with emphasis on everybody. “No footballer will ever approach such supremacy,” wrote Ayim Ohene, who saw Adjaye in his prime.

“He was awesome,” former Ghana President John Kufuor, who rates Adjaye as the best Ghanaian footballer he’s ever seen, told me in an interview in 2013. Kufuor had grown up in Kumasi, where James Adjaye, born and bred there, was practically deified while he served Asante Kotoko, the Ashanti Region’s “idol club”, all through his career. “The way he could juggle the ball at his feet — he’s so ingrained in my mind.”

Sometime in the late 1940s, James Adjaye made his debut for Asante Kotoko at the Kumasi Jackson’s Park — the ancestral home of football in Kumasi which preceded the Baba Yara Stadium. It was a derby game against Cornerstones, Kotoko’s local rivals. Adjaye was then still a young boy attending the Ordogonno School in Accra, yet he helmed the Porcupine Warriors so majestically, drawing praise and prophesies.

The Asantehene then, Otumfuor Nana Sir Agyemang Prempeh II, who would later marry one of Adjaye’s sisters, is reported to have said of the Number Ten that the men feared: “Someday, this young man will make great noise in the game.”

He would.

During the Gold Coast XI’s 1951 tour of the United Kingdom a few years later, Adjaye’s exploits drew these words from a British commentator: “The star of their (Gold Coast XI) side was once more James Adjaye, the inside left who with all things being equal could hold his own among the best of inside forwards in England.”

“His greatest misfortune was to be born at the wrong place at the wrong time,” Ayim Ohene wrote. “In today’s crazy world of football, his value would be difficult to assess: £100 million? The simple answer: priceless.”

At his peak, James Adjaye could make a ball do anything with both feet, creating freak feats. He was ‘King James’ to the Kumasi fanatics, but his nicknames stretched beyond: ‘Wizard Dribbler,’ ‘Master’, ‘Maestro’ ‘Professor’’ ‘Manager’.

He is smiling as I read out the appellations I’ve gathered from my research. “I would say it was a gift,” he says, humbly. “Even my older and younger sisters could play football.”

He told Ayim Ohene: “I was born to play football. I was hearing the shouts of spectators from Jackson’s Park right from my mother’s womb. This went on week after week for nine months, then I said, ‘Let me out. I want to play’”.

Even in Germany, at a time when he was in his twilight, his light was still bright. Tetteh remembers: “When we were in Germany, James joined a German Oldies club and they were all marvelled by his dribbling gift. There was no way you could stop him: he would dribble everyone and score. Anytime he had the ball, they would all just fall back and line up in goal, waiting for him.”

Adjaye reckons that both he and Briandt, like many of the footballers of their era, were ‘naturals’, blessed with what Kofi Badu described in 1955 as “a sort of innate ability”. “Our standard of play was way above that of today, honestly,” Adjaye claims.

Moro says same. “During our time, I can swear footballers here were better gifted,” he says. “I won’t lie to you.”

“Understanding, intelligence, ball control, dribbling, you name it –it was all there,” Adjaye says.

“If it were possible to line up teams of yesteryear against some of the current generations, you’d be shocked!” Tetteh boasts.

This abundance of congenital brilliance, Adjaye says, meant being taught football coaching in Cologne was a smooth, easy process for him and Briandt.

“We already knew the thing, but we were taught on top!” he laughs.

Briandt and Adjaye were to be the recipients of a quality-laden education in Cologne, under the supervision of the legendary German coach Hennes Weisweiler, that would eventually see them become Ghana’s pioneering batch of professionally trained coaches.

The plan was for it to have a domino effect: for them to come back and train others who would in turn train many others, until Ghana could boast of a sizeable population of professional coaches.

This arrangement was important because it was part of Nkrumah’s grand scheme of expanding the country’s independence outside of politics, right into sports.

The Ghana Amateur Football Association (GAFA), headed by the young, radical firebrand Ohene Djan, had employed Englishman George Edward Ainsley as Ghana’s first ever professional coach in March 1958.

Prior to that appointment, Ghana had never had a professionally trained coach working in the country. Teams improvised: coaches were either physical trainers, military men, footballers, businessmen with an interest in football — like Ken Harrison, Briandt’s coach at Hearts — or anyone experienced enough to train a group of footballers.

But things were bound to change once Djan and his men came into power preaching reforms. Djan had ridden on a wave of disaffection with his predecessor, Richard Akwei, accused of longevity and stagnant progress, to essentially lead a revolt that overthrew his regime in 1957.

Akwei, a stern and stubborn former School Headmaster nicknamed ‘Lion Heart’, had been the most powerful football politician in the Gold Coast for decades.

Djan accused Akwei of presiding over football that wasn’t ‘scientific’. One of his exhibits was the fact that national team, formed properly in the early 50s as the Gold Coast XI, had always lacked the touch of a professional coach.

This had especially been a major worry as it meant Ghana lagged behind Nigeria, their main football rivals who they played in the annual Jalco Cup Competition in the 1950s. The Nigerians had started hiring professional coaches from 1956, with the appointment of English coach Les Courtier. Ghana was late.

And so the Ainsley advent, masterminded by Djan and his people, represented a major political statement for his fledgling administration, hero’ing his persona while zero’ing that of his predecessor.

Later, this and many other subsequent achievements would earn his tenure the tag ‘Reformation era’. His profile soared, among fans and among sportswriters, earning him respect and endearment.

He was a powerful man, Ohene Djan. His wasn’t only sporting power, but political power too. He was a favourite disciple of Nkrumah, and there was an alleged reason why.

Nkrumah — upon his ascension to the post of ‘Leader of Government Business’ in 1951, a post that made him Ghana’s first indigenous leader — appointed Djan, then just 28, and then the Member of Legislative Assembly (M.L.A) for the Akwapim-New Juaben constituency, as his ministerial under-secretary for finance, as well as the chairman of the country’s Tender Board.

In 1954, Djan was imprisoned after being found guilty of misconduct in a high profile bribery scandal that rocked Nkrumah’s cabinet. Long after that incident, there were supressed murmurs in some quarters that Djan had not only covered up for his boss, but had sacrificed himself too, all in the name of loyalty.

The conspiratorial insinuation was that Nkrumah had been the corrupt culprit whom the Colonial Administration desperately wanted to crucify to justify their opposition to the local clamour for self-governance. Djan, per the theory, had taken Nkrumah’s place on the cross. “They couldn’t say it out loud,” says Tetteh, “but many people believed Djan had gone to prison for Nkrumah.”

Prior to his rise to power, Djan was not exactly a ‘football person’. Like Nkrumah, Djan saw the power of sports and made it a habit of supporting sporting events in his constituency and across the country by donating trophies. In the early 50s, there was an Ohene Djan Cup for football in Nsawam, and an Ohene Djan shield for female inter-college athletics.

“I remember he used to manage a boxer called London Kid,” Moro remembers vaguely, unsure of the full detail. It is a memory that is not far from accuracy, because it is a fact that in the 50s, Djan ran Madison Square Gardens Promotions as the principal promoter and match maker, and so he definitely must have dealt with Vincent “London Kid” Okine, a celebrated welterweight who in his prime was both champion of the Gold Coast and West Africa.

In football administration, Djan — unlike Akwei, who had administered football since the 1930s— was a man outside the establishment. He was a lay man. “He had no idea,” Adjaye simplifies. “He had to learn it all from scratch,” Moro adds.

After his turbulent spell as a politician, Djan, who was an Akwapim royal, had made his name as a tycoon who ran a wealthy family cocoa business in Nsawam.

But, dissatisfied with being on the side lines of political power, and seeking another pathway to it, Djan spotted an opportunity: football.

“He was smart,” Moro says. “He foresaw the rise of Ghana football and attached himself to it.”

“You could say he was an opportunist,” Tetteh adds.

But this was a typical politician, a master of the opportunistic art.

He found the fine mine of football, with all of its power and potential, and this pit was the perfect fit for his ambitions. He wanted in, and so he dived in at the deep end with careful calculation, bravely dipping his toes in the water.

He worked his way from the grassroots, organizing football competitions in and around Nsawam. He learned the ins and outs from experienced people, building contacts and popularity. (Tetteh recalls Djan inviting him to Nsawam to help organize a sporting tournament for the youth)

Djan wanted the sporting public to take note of him, to buy into his seeming enthusiasm for their passion, and he succeeded, warming himself into their minds and hearts.

He learned fast, rose fast. “He was brilliant,” Adjaye, who like Tetteh confesses he wasn’t really fond of Djan, admits. “He was very intelligent,” weighs in Moro, who was very close to him.

Djan wove his way around the politics, becoming head of the Nsawam Football Association, and later strategically positioning himself at the forefront of the agitation against Akwei.

Before long, he was on top of the chain: chairman of the Ghana Amateur Football Association at the age of 33.

He would go on to make a swift transition from tyro to doyen, achieving on an epic scale, exceeding expectations.

He founded the Black Stars. He got Ghana affiliated to both CAF and FIFA. He set up a successful national league and FA Cup. He brought in respected European teams of that era — the Dynamo Moscow of Lev Yashin and the Real Madrid of Alfredo Di Stefano among others — for tours.

He got the Black Stars to become the first African nation to tour Eastern Europe (1961) and the first Sub Saharan nation to qualify for the Olympic Games (Tokyo 1964).

He got local footballers trained as coaches in Germany and Czechoslovakia. He was the man behind the Black Stars’ most trophy-laden era: four Jalco Cup/Azikiwe Cups, three West Africa Football Championships, one Uhuru Cup, and two Africa Cups (Afcons).

And these were just football achievements.

In July 1960, he was unsurprisingly appointed by Kwame Nkrumah as Ghana’s first Director of Sports, heading the newly created Central Organization for Sport (COS) and manning it till the February 1966 Coup.

Operating in this new role which was at the level of a cabinet minister, and receiving enviable backing from Nkrumah — his salary was paid straight from the Presidency — Djan went to work, overseeing a period that saw Ghana placed on the sporting map of the world. He led medal-winning participations at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Italy and the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia.

At the height of his powers, Djan — who became a CAF Vice President and a FIFA Executive Committee member — was a bastion of influence.

The veteran Ghanaian journalist Razak El Alawa writes that Djan was “probably the greatest sports administrator in Africa during that time.” In February 1961, a Nigerian journalist named Bonar Ekanem wrote that it would take West Africa “a lifetime” to produce “a more capable” administrator than Djan.

Sir Stanley Rous, the former FIFA President and English FA Secretary, described Djan as a “valued” player at FIFA who was “a clear thinker and a lucid argumentator” and who had “a firm grip of problems associated with football promotion and development.”

Djan’s physique complemented his demeanour. He was young and handsome, thick and tall, manly and intimidating.

His communication skills were flawless — he wrote and spoke impeccable English. He could speak sweet and talk tough.

He had it all, and so naturally, he was a hit with people.

Men feared him, women loved him. He got people eating from his hands.

He was untouchable.

And so there was a lot he could do and get away with.

A lot.

George Edward Ainsley was a deeply knowledgeable coach — Sir Stanley Rous described him as “the most experienced coach in England” — and so his recruitment was seen by many as a big leap for Ghana’s football.

By the mid to late 1950s, Ghanaians football fans had become engrossed with a craving for ‘scientific football’ — a term for methodical football— something many believed Ghana desperately needed. This made Ainsley’s arrival timely. It was seen as the answer to this need: an end to the old ‘unscientific’ order, the dawn of a new ‘scientific’ era.

But beyond the excitement, GAFA knew a dependence on foreign technical expertise was never going to be sustainable in the long term. More importantly, they knew it was blatantly incongruous within the context of independence.

Nkrumah had always preached the importance of self-governance, of self-management, of ‘Africanizing’ the system by putting Africans in charge of African institutions. “The black man is capable of managing his own affairs,” he had famously echoed his independence speech a year earlier.

And so Briandt and co were being sent to Cologne for that prime purpose: to be empowered by knowledge that would aid them manage Ghana’s sporting affairs on their return.

Between Briandt and Adjaye, the former was the one earmarked to succeed Ainsley after the completion of the one-year course. He was shoo-in to become Ghana’s first black national coach.

But it was a destiny never to be fulfilled.

As part of their coaching program, Briandt and co first had to first spend some weeks at the Goethe Institute at Marquartstine, near Munich, studying the German Language.

Briandt had left Ghana in March. At the end of that April, he told the officials at the Institute that he was “returning home”, for reasons unknown.

Two weeks after he left, the Institute received a phone-call from Wilhelmina: Briandt was not back home, she said. The British Consulate in Munich said they had heard no word from him too.

Simply, Briandt was “missing”, according to press reportage of the issue.

It was not until late May that Briandt was found in Cologne, location of the Sports Academy, where he was scheduled to study coaching after language training.

What had happened?

“Since I arrived in Germany, I have been in a state of complete mental perplexity,” Briandt explained in an interview with Reuters upon resurfacing.

Why exactly?

Briandt, as it turned out, was no longer interested in becoming a professional coach, and had even written back to the Ghana Amateur Football Association to that effect. He had asked GAFA to write to the German Foreign Office to release and repatriate him.

The background: Before Briandt had left Ghana with Adjaye, Djan had asked the duo sign a bond obligating them to serve the Ghana Football Association as full-time professional coaches for at least four years after the completion of their course.

Briandt, now, had had a change of mind. “I want to remain an amateur,” he complained. “…all I can do now is wait for a decision from the Ghana Football Association.”

Briandt also recounted another circumstance which had contributed to his “complete mental perplexity”: he had arrived at the Goethe Institute late, two weeks after lessons had started.

The language instructor had told Briandt to study privately in his room due to him being behind time, and a frustrated Briandt had written back to H.P Nyemetei and his folks at Hearts of Oak, stating that he found staying in Germany “useless”, given the fact that the voyage of language lessons had set sail without him.

Briandt thus left the Institute for Bonne, location of the Ghana Embassy in West Germany, where he hoped to speak to a Foreign Service official about his desire to go home. He also alerted the West German Academic Exchange Service, which was paying for his stay and giving him allowances, about his predicament.

The Ghana mission instructed Briandt to proceed to the Cologne Sports Academy to await a decision from the GAFA. This left Briandt stranded and stressed. “As I do not like to stay in bed or do nothing while I am here, I am taking part in lessons and exercises at the Sports Academy,” Briandt said about what he was doing in anticipation of a decision on his situation.

Later, a West German Foreign Office official told Reuters that Briandt would receive a fully paid passage back to Ghana if he insisted on returning home.

Meanwhile, back in Ghana, Wilhelmina was relieved that Briandt was back on the radar at least. “I am happy this riddle is solved,” she told the Daily Graphic. “I never thought for a moment that he was missing, although I did not know where he was.”

Wilhelmina then went on to make an interesting revelation: Briandt, after being “found”, had written to her to emphasise that he would not stay in Germany to complete his course because he was “unhappy”.

The riddle had not been completely solved afterall.

Briandt’s unhappiness, which seemed to border on depression, was strange. He complained of feeling nervous. He claimed to be unwell. He said he couldn’t sleep.

Homesickness?

It was odd. But whatever it was, it was serious enough to drive him into a psychological crisis, and eventually into admission to the Cologne Hospital early in June 1958.

Alarmed by Briandt’s breakdown, Ohene Djan decided to engage a representative of the German Embassy in Accra. The meeting, held to discuss Briandt’s request to be repatriated, lasted 90 minutes.

The issue was delicate: Briandt’s determined decision not to become a professional coach was established, but he had, it was revealed, also written a letter to Kojo Botsio, Ghana’s Minister of Trade and the president of GAFA who had sought the scholarship, to say that he was willing to complete the 18-month course as a compromise if it wasn’t possible for the FA to repatriate him immediately.

But, as Briandt had added in the letter, after completion, he was not going to work for the FA as a coach for four years in fulfilment of the bond he had signed — he was rather going to go back to his regular job at the Kingsway stores.

Briandt was essentially saying he was willing to return to Ghana with a Cologne coaching certificate…but not to coach, or, in the words of Djan, “without placing the full benefit of the coaching course at the disposal of the nation”.

After the crunch meeting at the embassy, Djan signed a letter to be delivered to Kurt Protz, the Chancellor of the German Embassy in Ghana. In the letter, he had asked the West German government to withdraw the grant for Briandt’s schorlaship, thus shutting down the course and recalling him.

“Under these circumstances we honestly feel that in his own interest and that of the association, Briandt should be repatriated,” the letter said.

“Meanwhile, the Ghana Amateur Football Association shall be grateful if the government of the Federal Republic of Germany will be kind enough to consider the possibility of arranging for a new Ghanaian to replace Briandt at the next available opportunity.”

It is unclear what happened at the hospital, but by the time he was discharged after close to a month of treatment, Chris Briandt had changed his mind.

He now wanted to stay in Germany. He now wanted to complete his course in Cologne. More strangely, he apparently now wanted to become a professional coach.

In an interview with Reuters, Briandt, admitting that he was now feeling “much better”, said he had even requested for an extension of a year to his stay as he felt he could not “quite master the course” in the fifteen months left at that point. It was understandable: he had spent the first three months distracted and depressed.

Briandt then got in touch with the Ghana FA to apologize for the drama, to seek forgiveness for the “unpleasantness caused by my former decision”.

Ohene Djan, relieved and pleased by the U-turn, announced: “In the interest of Ghana soccer Chris Briandt should no longer be repatriated. He should therefore remain in Germany.”

There was something off about the entire situation, and one could not help but feel that the events playing out was just the tip of a giant iceberg.

Yes, he had been clear about the fact that he didn’t want to become a professional coach, but was that a serious enough reason for the psychological health issues he faced?

There was something more to it.

Tetteh alleges that in the early days following their arrival in Germany, Briandt had received a letter from one of his friends back in Accra.

In the letter was a rumour suggesting that Briandt had been betrayed by someone he trusted and respected back home.

It crushed him.

“We would see him weeping uncontrollably in his bed in the night,” Tetteh, who shared the same dorm room with Briandt, remembers. “He didn’t look all that healthy,” Adjaye, also in the same room, adds.

For days, according to Tetteh and Adjei, Briandt kept to himself. He wept when no one looked.

The letter’s claims had been hard to take, and it made him realize that leaving had been a mistake. Already, his initial reluctance to go, the ominous inkling that he had clearly felt, had been a burden enough, and now this piece of news had just pushed him over the edge. “It changed him,” Tetteh recalls. “He got mad and became nervous. He could barely concentrate on his course from then on.”

Well, that was until after time spent at the Cologne hospital changed things. Briandt emerged from treatment a changed man. He pulled himself together and got back on the grind, and although his request for an extension wasn’t successful, he still managed to power through to finish his course in the required time.

Chris Briandt touched back down in Accra on a warm Friday in July 1959, bustling with a lot of relief and belief after 16 months of drain and pain.

At the Accra Airport, Wilhelmina Briandt welcomed her husband in a manner so emotionally profound that it made the front page of the Daily Graphic.

She kissed him. She had missed him. A lot had happened in the 16 months he’d been a way.

A lot.

Briandt and Djan shared laughter while conversing during a walk to a waiting vehicle outside the airport. It looked like a happy scene of reunion, but deep down, Briandt suspected that laughter wasn’t the only thing he was sharing with his boss, and it must have taken a lot of strength and pretence to maintain a cordial composure.

Briandt’s return enjoyed anticipation and hype, and it was understandable. It was an exciting time: Ghana’s first professionally certified coach was in town. Also at the airport were Kurt Protz, and Andreas Sjoberg, Ghana’s new national coach who Djan had hired from Sweden to succeed Ainsley. Adjaye was scheduled to return in a fortnight due to an illness he had suffered in Germany.

At an arrival press conference, Briandt was upbeat. The future promised possibilities, bright and endless. “I have learnt enough about coaching,” he said. “And with the co-operation of the national coach, I hope the standard of Ghana football will improve greatly.”

Djan announced plans deploy Briandt and his colleague Adjaye to take up posts in Ghana’s Volta and the Northern Regions respectively.

These were areas that had a level of football development which considerably trailed that of the main four municipalities of Cape Coast (where football in Ghana was born in 1903), Accra, Kumasi and Sekondi.

Djan wanted the duo to develop interest and talents in order to raise their standards to become at par with the big municipalities. He wanted Ghana to be a full-blooded football hub.

When Adjaye made his own return to Ghana two weeks later, he came with a present: the contingent of Fortuna Dusseldorf, one of West Germany’s biggest clubs.

Djan had managed to invite them to tour the country, in an effort he hoped would be an educational experience for Ghana’s footballers. Fortuna were to play a series of friendlies with some of Ghana’s leading teams: Hearts of Oak in Accra, Hasaacas in Sekondi, Asante Kotoko in Kumasi and a Southern Ghana Representative side in Accra.

Briandt’s first task as coach, after a two-week holiday spent reacclimatizing and catching up, was to coach the Hasaacas team to meet Fortuna. Then he was to assist Sjoberg in coaching the Southern Ghana team, which was essentially a quasi-national team, due to the fact that most of the nation’s top players were based in the South.

Under Briandt’s technical tutelage, Hasaacas forced Fortuna to a 3–3 draw in Sekondi. The rest of the teams struggled: Hearts were beaten 3–2. Kotoko lost 4–3. Southern Ghana got hammered 6–1.

The fact that Hasaacas recorded the best Ghanaian result from the Fortuna series made one thing clear: Briandt had talent.

And the thought that he had just started made people excited.

Surely, there was more in store.

Well, apparently not.

After Fortuna’s tour of Ghana, Djan formed the ‘Black Star Group’ (later to be simply known as Black Stars); a new national team to replace the erstwhile Ghana XI. He appointed Briandt as assistant coach of the team.

Djan hoped the experience of understudying head coach Andreas Sjoberg would prepare Briandt for the top job, because he had plans of ultimately promoting him.

But there was a problem: Briandt, again, was apparently no longer interested in the main job.

Heck, he was not even interested in coaching itself.

So disinterested, in fact, that when the Black Stars started playing matches, their assistant coach was nowhere to be seen.

He went AWOL.

Initially, people downplayed his disappearance. Maybe he was sick. Maybe something important had come up. And so they ignored it. Let it slide.

But soon, its prolonged nature forced eye brows up. Something fishy was going on.

And so the questions began to brew. Where was Chris Briandt? Why had he unceremoniously left his post? What was going on?

The high level of public concern was justified because the state had invested a lot to get him professionally trained. He essentially owed Ghana service, and this made people feel entitled to know why he wasn’t doing that.

“The general public would like to know what contributions Christian Briandt is making to Ghana soccer after his training in Germany,” demanded Daily Graphic Sports writer Sam Boohene, who attempted to investigate the issue. “We have waited a long time for a statement from GAFA but no statement has been made.”

The only trace Briandt left, the only clue the public had, was his car.

It was an official car bought for him as part of his entitlements as a national coach employed by the State through GAFA. The car was strangely parked at the residence of Ohene Djan at Nsawam, just outside of Accra, rather than in Ho, where Briandt was supposed to be based.

As per Djan’s typist, who spoke with the probing Sam Boohene, Briandt had driven all the way from Ho to Djan’s home in Nsawam to return the car, saying he did not “want” it and that he considered it “dangerous” to drive it.

Something wasn’t right. In 1959, owning a car was a big, big deal in Ghana, and here was a man offered a free car returning it with a bizarre, if not unsatisfactory explanation.

Djan, of course, was supposed to have answers. But strangely, when asked, he was evasive in his response. Parabolic, even. “Briandt is of age and is purely responsible for his actions,” he told Boohene. “I think he is the proper person to say whether he has quit soccer or not.”

Djan went on to say that he and GAFA still recognized Briandt as coach. That they waited to hear from him. That they could not “force” him against his will.

On whether Briandt was still being paid, GAFA Treasurer Jellico Quaye remained tight-lipped, but Djan, when pushed to the wall, retorted: “How can he be paid when he is not working?”

That was the thing: Why was he not working?

What was going on?

The temperature of concern rose, and with it suspicion, sparking an avalanche of public enquiries.

In December 1959, a fan named S.B Agyemang from Kumasi wrote to the Daily Graphic under the title “WHERE IS CHRIS BRIANDT?”- words that were on the lips of many fans. “In the interest of the general public, may I ask the chairman of the Football Association to come out with an official statement on coach Briandt?”

“As matters stand now, those of us who are interested find it difficult to appeal to Briandt to resume coaching duties because we don’t know why he is not at his station in Ho,” wrote another fan, Kwasi Akufo from Pusiga, Northern Region, in a note to the Graphic in January 1960 titled: “WHAT IS THE LATEST ON BRIANDT?”

“Unlike his colleague Chris Briandt, who will not go to his station or say why he won’t go, we hear (James) Adjaye is taking his job seriously in the North,” wrote S.K Owusu Ansah, another fan writing to the Graphic, in February 1960. “By the way, how long will the Football Association and Chris Briandt turn a deaf ear to the repeated appeals by fans for an explanation of the dark cloud that surrounds coach Briandt?”

The Briandt saga became a mystery pregnant with many questions, in desperate need of a C-section — because Briandt and Djan, the two people who definitely knew what was going on, remained mute, stifling a normal birth of answers.

Days passed. Months too. Yet nothing was forthcoming: not Briandt, nor his reasons for abandoning his privilege as the heir apparent to Ghana’s national coaching seat.

In March 1960, however, the National Council of GAFA released a statement confirming that they had released Briandt from his role as coach to go back to his former post as Manager at the Kingsway Stores. In a strange continuation of the general feel of concealment, GAFA gave no explanation for their decision.

The Daily Graphic didn’t take this lightly. In a scathing editorial, the paper barked at GAFA. “We have the greatest admiration for the chairman and council of the Football Association,” it said. “But on this Briandt issue we think that they have sadly underestimated the intelligence of the general public.”

Briandt was trained “at public expense”, the paper reminded, and thus the public had every right to be “interested in his official activities as coach”. “Is it not realized that information about public organizations is not private property?” it asked.

The paper continued to question with intent — “Whose fault was it?”. “Who shielded who” — but no answers came. “No one outside the council will ever know what really happened,” it concluded begrudgingly.

Meanwhile, the public continued to grow frustrated by the lack of information. They were losing patience. “Briandt went to Germany with public funds to train as a football coach and not train for Kingsway stores,” a fan complained in Graphic.

Soon, the frustration became disappointment, the disappointent graduating into bitterness.

They turned against Briandt. They demonized him. They verbally abused him. Fans who had once adored him now began to abhor him. . They called him a traitor, called for his arrest.

But little did they know that Briandt had quit because he felt someone had betrayed him too.

To know what exactly happened, we’ll need to rewind all the way back to Cologne, in that dorm room, when Briandt received that letter.

What was in it that shook him so much?

Briandt had apparently found out about a rumour which, till this day, remains shrouded in secrecy due to its sensitive nature.

“One of his friends had written to tell him that Ohene Djan was chasing Wilhelmina,” Tetteh reveals.

“Yes, it’s true,” Adjaye confirms. “We heard that Djan had gone after Briandt’s wife.”

“Many years have passed, yet it still remains a case that the few people who know don’t like to talk about,” Moro adds.

Moro knows better, because unlike Briandt and Adjaye, he was in Ghana when it all happened.

He explains: “The thing was, Ohene Djan — in an effort to console Briandt’s young wife, owing to the fact that he had sent her husband away — became very close to her. He began taking her along everywhere he went just to make sure she wasn’t bored or depressed.”

Functions, stadiums, hotels, home — Djan and Wilhelmina seemed to go everywhere together. “They even travelled together during our 1958 Jalco Cup game away in Lagos,” Moro reveals. “As you would imagine, this was never going to end well.”

The problem was, as Moro opines, that it was difficult to argue in Djan’s defence. It was hard to believe he’d done what he’d done inadvertently or innocuously. And the reason was simple: Wilhelmina was young and attractive and vulnerable, and Djan, like most other great men, had a harrowing Achilles heel — a weakness for women, to put it mildly. Those who worked closely with him, including Moro, Adjaye and Tetteh, knew.

This complicated things, Moro explains. Per how it all looked, many witnesses were convinced that an affair had occurred. Adjaye and Tetteh, from their own observations and experiences, believed it too. “From the outside, it definitely looked like something was going on (between Djan and Wilhelmina),” Moro says. “Well, at least everyone thought so. Basically, it was like, even if he (Djan) hadn’t done it, he had done it.”

Indeed, whether Djan had done it, whether he had been guilty of the charge of adultery, of wrecking Briandt’s marital home, is something that will eternally be the subject of opinion or speculation. Djan, who died in March 1987, of course, never admitted to it in his lifetime. The case never even made it to the public space.

But, for Briandt, it was neither speculation nor opinion. That Djan had betrayed him was truth, as far as he was concerned, and he believed this perceived truth so much that it affected the decisions he took in his life from thereon.

“Briandt left the job because he didn’t want anything to do with Djan after what had happened,” Tetteh explains.

The public, of course, had not known this, and so they continued to antagonize Briandt. Yet, even amid these strong waves of antagonism, Briandt would continue to remain anchored in his decision to retreat, not to speak. He would continue to insist on staying away from greatness. “He hid himself from everyone,” Tetteh says. “We never knew where he was hiding,” Adjaye adds.

He played a few more games for Hearts before finally hanging his boots, at the age of 30, in 1959.

In 1961, when Hearts of Oak turned 50, Sir Stanley Matthews wrote a letter to the club’s coach, asking specifically of Briandt. “I hope Hearts will persuade Chris Briandt, their former captain, to play at least one match for them in their jubilee year,” he wrote. “I hope that you personally (Harrison), Accra Hearts of Oak and I am sure, many football supporters regret his premature retirement.”

Following this premature retirement came a difficult aftermath. “His life became messed up,” Moro says.

But this was an understatement.

Briandt went through a heart-breaking break-up up with his wife, going on to endure a painful yet deliberate withdrawal into quietude and obscurity, one that would see his legend and legacy totally fade out, and one that would last until his death.

He continued to work at the Kingsway Stores, retiring aged 52 in 1981, switching jobs by becoming assistant transport officer at the office of the Ghana Revenue Commission. He finally left public service in 1997, and continued living as an avowed recluse until 2004, when he made his first public appearance at the Alisa Hotel in Accra as part of a function to honour him.

The Ghana News Agency’s Richard Avornyotse took advantage of Briandt’s rare appearance on the radar to track him down for an interview, bringing his story to a generation of football fans who hadn’t the slightest idea who he was.

He had to be reintroduced, his story retold.

In August 1951, when Ghana was then a British Colony known as the Gold Coast, the national football team, known as the Gold Coast XI, travelled for a tour of the United Kingdom engineered by Richard Akwei.

The team was made up of 20 of the country’s most talented footballers, all technically amateurs, and all without boots.

Yes, playing barefoot was the norm, and these players were to be ambassadors of this culture in the U.K.

Somewhere in the middle of the tour — where they played 10 games and lost as many as eight — substantive captain of the team, 28-year-old Timothy Darbah, was stripped off his captaincy by Akwei for leading player agitations for an increase in their allowance.

The new captain selected to replace Darbah was a strange, surprise candidate.

He was the quietest member of the squad. At 22, he was also one of the youngest.

His leadership qualities seemed inherent — indeed, at his club, Hearts of Oak, he had been made captain in 1950, just a year after making his senior debut — yet the expression of this leadership, per his unassuming personality, seemed too subtle.

But the authorities were convinced by this subdued sense of authority. And so they bestowed the honour of national captaincy on the young man: Emmanuel Christian Briandt.

Briandt’s quietness had a gravitas about it, and this made his teammates shy of him. “Even referees were shy of him,” Dogo Moro says.

That is how he earned his respect, how he managed to establish control. It was unorthodox, but it seemed to do the trick.

He would vindicate this vote of confidence by going on to lead the team to many victories in the subsequent years, especially in the Jalco Cup against Nigeria — with victories in 1953 and 1955, the latter being a historic 7–0 thrashing.

Briandt would later refer to the 1955 Jalco Cup massacre of Nigeria — which later resulted in him being named the Gold Coast’s Sportsman of the Year — as his most memorable match in a national shirt. And this was not because of the odd score line per se, but because the team, for the first time, played in boots — and he had been major part of the reason why.

Briandt and C.K Gyamfi — who would ironically go on to become Ghana’s first black coach, fulfilling a destiny that for many years looked like Briandt’s — had both bought and brought back boots from the U.K to champion its use locally. But they were met with riotous resistance.

The people rejected the boots because playing barefoot had become an entrenched comfort zone. The rejection was so intense that Briandt and Gyamfi — Accra and Kumasi based respectively — found themselves being dropped from teams during matches owing to their insistence on playing in boots.

But that resounding victory over Nigeria — Ghana’s biggest ever in the history of the ‘Jollof derby’ rivalry — became the sermon for the propagation of the truth of boots, “killing the debate”, as Briandt himself put it.

This achievement was not a one-off. Throughout his career, Briandt had used his position as the most regarded footballer in the land to drive positive change. Almost flawlessly, he had led by example, had gone through a lot to serve his country diligently, only for it all to go down the drain when it mattered most.

When the G.N.A asked why he turned down a chance to go into the history books as Ghana first indigenous head coach, Briandt — even after 46 years of silence — still avoided digging up Djan-Wilhelmina scandal. He didn’t want it on public record, even if it meant exonerating himself. The man couldn’t be controversial to save his own name.

Instead, he said that he had declined to coach the national team because of “good judgement”. Coaching was an art he felt he wasn’t cut out for, he said. He felt out of place, he continued, found himself jittery anytime he sat on the bench. He lacked what it took to control players, he confessed. He was the type to plead with them when he was supposed to be ordering them, he added.

It was all true, to be fair, but it wasn’t the entire truth, and it most certainly didn’t help his case. But for him, it didn’t matter, because the damage had already been done, and he’d spent many decades being at peace with it.

He had let it all go, too. “I am a pacifist,” Briandt said. “I have forgiven those who caused me pain.”

The agony of the alleged marital infidelity had not only driven Chris Briandt to hang his boots prematurely, it had essentially pushed him to apostatize.

He renounced and severed ties with football, a religion he’d known, loved and practised since his school days. “I loved the game so much,” Briandt told the G.N.A. “Anytime a referee whistled for the end of a match, I became sad and rather wished the game would never end.”

Yet, after 1959, this love turned to disgust. He became disillusioned. Briandt was, as Ayim Ohene wrote, “brutally betrayed by the game he loved and mentally subverted by the authorities he relied on”.

“His anger, frustration and disbelief pushed football completely out of his memory,” Ohene continued. “He stopped watching football,” Tetteh adds. “He didn’t want anything to do with it.”

It was a tragedy he would take to his grave.

On October 18, 2008, Briandt bowed out of life in a manner typical of how he’d lived — no crowd, no loud. His death, much like his last 49 years of life, occurred on the blindside of many.

There were no newspaper tribute spreads, no radio or TV discussions on his legacy, no state burial — nothing. No one knew him, and the few who did had forgotten him.

Beneath a nondescript grave at the Osu Cemetary in Accra, ironically overlooking the Accra Stadium, lays Ghana’s greatest football captain. His funeral, according to Tetteh, had not even been able to attract a 100 people.

“What pained me, and in fact still continues to pain me, is that his funeral was poorly attended,” recalls Tetteh. “I was at the cemetery. They couldn’t even get him a proper grave — it was a very narrow place where they’d buried someone else and they sort of fixed him in there somewhere. I’m not even sure they completed it.”

Tetteh remembers visiting Briandt at his home in Maamobi in his last years, and being heartbroken about how miserable he had become. “He looked really wretched and his home was so old. Everything was dirty. If you saw his room, you’d vomit” he says, shaking his head.

It was an anti-climax to a life that once looked so promising.

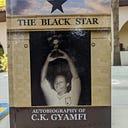

“He could have become great,” Moro says. “He could have become like C.K Gyamfi.”

Briandt wasn’t the only one who could have become like the great C.K Gyamfi, whose status as one of the most accomplished personalities in African football history is sealed.

Adjaye could have, too — except that when Briandt turned down the national coaching job, he (Adjaye) was bizarrely bypassed even though he was next in line. “I wouldn’t be able to tell if it was just business or something personal,” Adjaye says of his snubbing.

C.K Gyamfi, the third in line, would ultimately get that honour.

Gyamfi was the third Ghanaian footballer to train as a coach. In 1960, Djan sent him to Germany to study, and he returned to work for GAFA as a coach, working in various capacities while understudying the national coach Josef Ember — a Hungarian who had replaced Sjoberg.

In January 1962, Djan promoted Ember to ‘Technical Advisor’ and made Gyamfi — then 33-years-old — Ghana’s first indigenous head coach.

There was no doubt that Gyamfi’s ascent to that high honour was based on merit. As a player, the Daily Graphic hailed him as “Ghana’s greatest” in 1960, and as a coach, he would go on to become the greatest, winning the Africa Cup of Nations a joint-record three times.

But even Gyamfi, who died in September 2015, would have admitted that every great man needs something peculiar to work for him at some point in order to access certain extraordinary opportunities.

So what worked for him? Well, Ohene Djan may have correctly hailed Gyamfi as a ‘natural coach’ and ‘the greatest initials in our history’, but all that wouldn’t have probably mattered if he hadn’t been a Home Boy.

A Home Boy, in that era, referred to any man from the Eastern Regional Akuapim tribe who worked within sports. Djan, who coined and popularized the term, was himself an Akuapim, and according to witnesses of that era, used to favour his kinsmen. “One thing I didn’t like about Djan was his ‘Homeboyism’,” Tetteh says.

Djan’s right hand man at GAFA, Benjamin Brako Bismark, was another Home Boy. B.B Bismark hailed from the same Akuapim home as Djan and had served him loyally since his political days of early 50s, ultimately being rewarded with a post as Team Manager of the Black Stars when Djan rose to power.

There were many other Home Boys within Djan’s set-up. “Even the drivers who drove us (Black Stars) were Home Boys,” Moro says.

Basically, you needed to be a Home Boy to be in Djan’s circle, to be a beneficiary of his power, and Adjaye, an Ashanti, unfortunately was not. And so he missed out, with Djan deciding to keep him in the Northern Region rather than to bring him down to the capital to fill in after Briandt’s disappearance.

Disappointed and disenchanted, he retired from coaching in 1962, just three years after returning from Germany.

And now, like his friend Emmanuel Christian Briandt, James Kenneth Adjaye is a forgotten hero.

“To be frank, no one remembers us,” he says.

“And it’s a big mistake.”

First published on Business Insider Africa.