The Mfum Myth: Inside the story of the shot that tore through a goal net

Fiifi Anaman tells a fascinating tale that strangely links an American president who got shot, a Ghanaian footballer whose shot tore a goal net, and a Ghanaian journalist who mourned the former remotely and witnessed the latter in close proximity.

After Stanley Matthews’ fine form had fired up the 50s, and George Best’s silky skills had served the 60s, another famous British footballer emerged in the 70s.

He burst onto the scene in August 1973 — a rare breed unearthed from the obscurity of the Hebrides, remote islands off the Scottish mainland.

He was a man-mountain, built like a brick outhouse: 6 foot 10 inches tall, bull-neck, bulging biceps, barrel-chest, thick thighs and chunky calves — glaring evidence of his past as a caber tosser (a Scottish sport that is like the discus throw, except substitute the discus with wooden poles that are almost 6 meters high and 175 pounds heavy). The man was a bulldozer, basically what you’d have if Marvel Comics’ “The Hulk” decided to trade his superhero duties for football.

There was more fascinating style to his brawny brand: He wore shirts far too small for his macho torso; His muscular midriff was almost always exposed; He donned size 16 boots.

A goal machine, he was the delight of football fans — especially young boys — across Scotland and indeed the whole of the United Kingdom. He was a beast in the box: He would latch unto rebounds with “the speed of a pouncing puma”.

But, his trademark move, his powerful patent, was his shooting. He was famous for possessing the hardest shot in football. When his steely feet booked a flight with the ball, it flew first class, with the speed of a Concorde and the ferocity of a cannonball. He would hit the ball so hard that it would rip right through the goal net.

Who was this hotshot whose shots, hot to handle, could neither be tamed by goalkeepers nor by goal nets? And how come you’ve never heard of him?

His name was Balfour.

Hamish Balfour.

Fans from France called him Hamish Le Foudre.

The British simply called him Hot Shot Hamish.

His parents were comic strip artists; writer Fred Baker and illustrator Julio Schiaffino, because, like The Hulk, Hot Shot Hamish was not born, but created.

He was only a comic character.

He was not real.

If Hot Shot Hamish were real, who would he be?

Probably the former Brazilian left back Roberto Carlos, whose shots, especially from free kicks, mesmerized with their strange trajectory and pure power.

Carlos was never at loss around a dead ball: A goal he scored for Brazil against France in 1997 was hit so hard and so skilfully that it completed one of the most astonishing curves ever witnessed, with pundits describing it as the “goal that defied physics.”

In fact, physicists from France later sat to analyse the goal, and told the BBC in 2010 that the man who finished 1997 as the world’s second best player had managed to “minimize the effect of gravity” to beat French keeper Fabian Barthez from 35 meters out. Carlos no doubt had the hot shot down pat, but at a diminutive height of 5ft 5, he does not tick the physique box.

Another good shout for Hot Shot Hamish would be another Brazilian, Givanildo Vieira de Sousa, who plays at Shanghai SIPG in China. We all know him as Hulk, a nickname given to him by his father, inspired by the comic character. Not only does Hulk come close to the physique at 5ft 11, he has the hot shot to boot too.

There is a video of him from 2015 blasting a shot so hard that it sends the keeper flying right through the net. It is, however, later revealed by the Daily Mail to be an “elaborate and staged routine” from training — the hole in the net had been cut in advance — but that takes nothing away from the wicked weight of a Hulk shot. “When his left foot unleashes a thunderbolt on target…” claimed the Bleacher Report in 2012, “…the goalkeeper has to be prepared to get stung or see the goal net bulge.”

Here’s another wild candidate, who may be the best fit: Hot Shot Hamish would have been a Ghanaian. And no, not Tony Yeboah — whose rocket shots for Leeds United in the 90s remain iconic highlights of the Premier League’s early years, and who ranked third after Hulk and Roberto Carlos on 90min.com’s list of “players with the most powerful shots in the history of football”.

This Ghanaian, named Wilberforce Mfum, forced a goal net thread wide open with a hot shot in 1963, almost a full decade before the Hot Shot Hamish character debuted in the UK’s Scorcher comic magazine.

Unlike the Hulk shot, there is no video of this feat.

Yet unlike the Hulk shot, this was no stunt.

The first goal Ghana ever scored in the Africa Cup of Nations was a controversial one.

It happened on Sunday, November 24, 1963.

Ghana, having become independent six years before, was hosting the 1963 Africa Cup of Nations (Afcon).

Having missed the first three editions of the Afcon, the country’s national team, named Black Stars, were making their debut in the continent’s flagship football competition.

They were at that point arguably Africa’s most popular national team due to their exploits. They were three-time champions of West Africa, and had gone on an unbeaten tour of East Africa. In 1960, they had beaten Blackpool, FA Cup winners in 1953 and English league runners-up in 1956, by five goals to one in Accra. In 1961, they had won eight out of 12 games from a tour of Eastern Europe. In 1962, they had drawn 3–3 with Real Madrid, then five-time European champions, featuring Alfredo di Stefano and Ferenc Puskas.

By 1963, the Black Stars were considered kings without crowns on the continent, and were determined to turn that year’s Afcon into a coronation.

Tunisia were their first opponents, and the game was barely 10 minutes old when controversy struck.

The West Africans were celebrating a goal. The North Africans were protesting that goal.

Was it a goal line issue? No. Was it an offside? Not quite. Was there a foul factor that had been missed? Well, more like a wow factor.

For the delegation of Ghanaians in and around the field, coupled with their thousands of Ghanaian fans in the stands, it was a goal, and their reason was simple: The ball had entered the net.

For the eleven Tunisians on the pitch and their officials on the bench, it was not a goal, and their reason was even simpler: the ball was not in the net.

Something didn’t add up.

It was up to Egyptian referee Mahmoud Hussein Imam to decide for both sides. Having been an international referee since 1956, and one of only two African referees at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Imam was a seasoned arbiter. He knew the rules, knew how to run the rule over difficult scenarios such as this one.

Besides, he had also been at the center of Ghana’s crunch 1962 World Cup qualifier against Morocco at this same ground in 1961. He was familiar with this stadium, with the stress of its demands from the stands. He was not one to be fazed by the stakes of the ocassion.

Surely, he would have an answer.

So, goal or not?

Imam had no clue.

He had to call for backup, had to consult his linesmen.

What in the world was happening?

The events surrounding that goal had been as baffling as events surrounding the sudden assassination of American president John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK) just two days before the game, the tragedy that had inspired the minute’s silence that had been observed before the match had started.

Both sides were right — the ball had entered the net, and the ball was not in the net, and in this confusing contradiction lay the cause of the chaos.

And it was a challenging chaos, one that would transform Imam and his linesmen from referees into detectives, because they had to go over to investigate the Tunisians’ goal area.

Their findings? Intriguing.

“Shot tears net!” the Daily Graphic newspaper’s match report revealed.

How?

“They inspected the net,” the report explained, “and when they found it completely torn, they ruled it a goal.”

One-nil, Ghana. The bewildered Imam took out his notepad to record the details of the mystery goal.

Minute?

8th.

Scorer?

Wilberforce Mfum.

“Mfum sent the packed stadium roaring with a thunderbolt shot…It was a first class shot that went right through the net…”

— Daily Graphic match report of Ghana v Tunisia; Opening match of the 1963 Africa Cup of Nations; Monday, November 25, 1963.

There is an anecdote told by former Ghanaian footballer and author Alex Ayim Ohene in his book “The Glory Days”: A reporter, the story goes, once asked Ghanaian goalkeeper Addoquaye Laryea just how powerful Wilberforce Mfum’s shooting was.

Laryea “simply pointed at the net to reveal a hole and the livid bruise in the corner, with no further comments.”

It is not known if this story is true, but it is true — although not largely known — that Mfum did indeed create a hole in a net with a livid shot one fateful Sunday afternoon in November 1963.

Against Tunisia at the Accra Stadium, Mfum, whose boots were “packed with gunpowder”, had “hammered the ball through the net and into the crowd,” according to Ayim Ohene.

Every Ghanaian boy who grew up loving football once heard the story of this net-breaking Wilberforce Mfum shot, the same way most British boys from the 70s to the 90s were acquainted with the legend of Hot Shot Hamish from their comic books.

Sadly, this event — popularized by the phrase Mfum atete net (Mfum the net tearer) — is largely considered to be a myth.

But it isn’t. It actually happened.

It actually happened.

“The shot was just from the edge of the box.”

This is Emmanuel Kwaku Bediako, who witnessed that shot.

“Everyone was confused,” Bediako remembers. “Our players were sure it was a goal but they couldn’t prove it until the linesman was called.”

Bediako was 22 then, a cub in the press hub. He had just started out as a junior writer with the Daily Graphic.

It was an exciting setting. The Accra Sports Stadium, opened just 11 years before and hosting its first ever Africa Cup match, was filled to capacity, immersed in a carnival atmosphere, but Bediako was not entirely plugged into the euphoria.

For at least two nights preceding the game, he had been dealing with insomnia, caused by grief from the demise of the world’s most popular Commander-In-Chief.

The minute’s silence observed before the game had been a reminder of this grief.

Bediako was, he remembers, still mourning the Kennedy tragedy.

“When he died, I couldn’t sleep,” he says.

Why would a Ghanaian be that fond of JFK, the man they called Jack?

Where from that bizarre, special bond?

Despite unofficial yet glaring leanings towards the Eastern Bloc, Ghana’s leader then, Kwame Nkrumah, held JFK, the ‘Leader of the Free World’, in high regard.

This is because JFK had been influential in the US’s agreement to significantly fund the Volta River Hydro Power Project (Akosombo Dam), heralded as the “the largest single investment in the economic development plans of Ghana”.

When Nkrumah visited the White House in March 1961 to hold talks with the 35th President of US, he remarked: “Meeting you has been a wonderful experience for me…and I really mean that.”

In November 1964, Ghana held a memorial mass for JFK at the Holy Spirit Cathedral in Accra — the headquarters of the Catholic Church in the country. Even after a year, the memory of JFK’s death was still “fresh on our minds”, as Nkrumah wrote in a message to Jack’s widow, Jacqueline Kennedy.

Nkrumah would later invite Mrs Kennedy as a special guest at the inauguration of the Volta Project in February 1966, although she would be unable to make it. But that wouldn’t stop Nkrumah from assuring her of a “warm and truly Ghanaian welcome” anytime she decided to visit.

In his tribute to the American statesman following the infamous assassination, Nkrumah eulogized JFK as “a remarkable man”.

Bediako agrees.

If Nkrumah admired JFK, Bediako was obsessed. As a young reporter, Bediako followed the youngest elected US President keenly through all 34 months of his short presidency. “The way he spoke…I liked everything about him,” he confesses.

Everything, especially the name.

Today, Emmanuel Kwaku Bediako is a veteran of sports writing, with close to 60 years of experience. He is the celebrated author of The complete history of the Ghana Football League, arguably Ghana’s most popular football book.

You probably know him as Ken Bediako, because he changed his name in honour of President Kennedy many years ago.

Ken Bediako reckons that Mfum would have found it hard repeating the feat today because of the structure of modern day goal nets: They are hung loose and perpendicular behind goal posts, with enough space between the goal line and a net which is without much tension, making them more accommodating of shots.

That is why in 2006, Brazilian midfielder Ronnie Heberson could not break the net despite hitting a free-kick that travelled at a speed of 210.8 km/h, covering a distance of 16.5 meters within 0.28 seconds — the fastest shot ever recorded in football.

That net at the Accra Sports Stadium 57 years ago, like most other nets in that era, were hung tight and diagonal, very close to the goal posts. The tension within them made such nets hostile to a hard shot: they either pushed it out or gave in to it, and Mfum’s famous shot that day saw a rare occurrence of the latter.

“I remember Mfum’s teammates teasing him about the net being weak,” Bediako, who is now 79, grins.

But while the net may not have been structured to withstand an Mfum shot, Mfum was structured to produce such pile drivers.

Not only was he built to shoot — “He was a no-nonsense attacker, and behaved like a hawk in the box” says Bediako — he was built to shoot like that. “He was nicknamed Bulldozer and Man Diesel for his aggression and brute strength,” Bediako adds.

Standing at 5ft 9 inches, Mfum was also heavy in the right places. “His torso and legs, bloody hell,” Ayim Ohene marvelled. It was thus no surprise that his shots were “explosions of the right foot” that carried “devastating velocity”, according to Ayim Ohene.

But Ghanaians were used to seeing such shots during that era.

Let’s take Edward Acquah, for instance. Hailed by Kwame Nkrumah as “Ghana’s greatest match winner”, Acquah was Mfum’s Black Stars teammate and friend, and together they were nicknamed the “TUC giants”.

According to Ghanaian journalist Cameron Duodu, Acquah was “powerfully built” at 6ft 2 and around 180 pounds in weight — another candidate for Hot Shot Hamish, if you think about it.

Acquah, who famously scored a brace against Real Madrid and a glut against Blackpool, was nicknamed The man with the Sputnik Shot — apparently because his shots were out of this world, like ‘Sputnik 1’, the earth’s first artificial satellite launched by the Soviets in 1957.

How about the story of Ghanaian goalkeeper Samuel Lamptey Mills, when he came up against the legendary striker Tesilimi Balogun, Nigeria’s version of Edward Acquah, and another West African Hot Shot Hamish?

Balogun, while on a 1955 visit to Ghana (then known as the Gold Coast), featured as a guest player for Great Ashanti in a match against Hearts of Oak in Kumasi.

In the course of that game, he fired many thunderous shots — true to his nickname Thunder Balogun — that eventually sent Hearts goalkeeper Lamptey Mills, then the country’s safest pair of hands, straight to the Korle Bu Hospital for treatment.

Let’s rewind further back to 1951 for our next exhibit. The Gold Coast national team, known as the Gold Coast XI, was touring the UK and playing barefoot, as was the culture then.

In their first match in England, against a side from Romford, the team’s captain, Chris Briandt, hit a free kick so hard that it left British spectators wondering if his legs were made of steel. “The ball went like a bullet,” a Daily Graphic report read.

That free kick, struck from “well outside the penalty box”, with a right foot that was only bandaged with sock-tape, was described as “the biggest surprise the Gold Coast team gave the crowd.” “There can be few players in Britain who can hit a dead ball so hard even with boots on,” the report praised.

So what shaped this culture of sharp-shooting?

Here’s an explanation from the horse’s own mouth.

Meet Wilberforce Kwadwo Mfum, the net tearer, and the real life incarnation of Hot Shot Hamish.

“In that era we didn’t pass a lot around the final third — we were encouraged to shoot from all ranges and angles,” Mfum tells me. “So we became really good at it.”

Mfum reckons he was given the nickname Bulldozer because he was hard to dispossess while with the ball at his feet. Ohene Djan, Ghana’s monumental Director of Sports in the 60s, called Mfum a “powerful individualist” and a “fearless mine-sweeper”.

Due to this, Willie, as Mfum was later known, thus often had the confidence to decide on the ball’s destination, and the luxury of time to swing his right foot — described by Djan as “lethal” — at the ball, in order to give it the wings of power to fly into the net — or through it.

“Ah, your generation? You are not watching real football,” Mfum boasts, with obvious nostalgia.

“We played with our hearts. We loved the game.”

Ghana would go on to win the 1963 Afcon, and that Wilberforce Mfum goal would prove crucial: If Ghana had lost that Tunisia game, which eventually ended 1–1, they would have complicated their chances of qualifying for the knockout phase, which would have ended in early elimination — an unthinkable disaster on home soil.

Mfum’s rise to national prominence saw him emerge from Ghana’s central region, where he played for Swedru All Blacks and Venomous Vipers, through to Kumasi, where he played for Great Ashanti, and finally, for giants Asante Kotoko, the ‘Fabulous Club’.

In his prime, Mfum was a prolific merchant in the business of goals, second only to Edward Acquah in that era. He scored so consistently that Kotoko bankrollers B.K Edusei and F.Y Frimpong made him one of the first Ghanaian footballers to own a car.

But as a character, Mfum was as controversial as that goal he became known for. He wore his heart on his sleeve in a bid to win games, and this show of passion made him notoriously temperamental, so much so that he often landed in disciplinary issues.

In 1962, following a game between Asante Kotoko and Real Republikans, Mfum received a six-month ban for not only challenging a penalty decision by the referee, but also accusing the referee of ending the game five minutes from time.

A year later, coincidentally following yet another Kotoko-Republikans duel, Mfum was slapped with a one year ban — later reduced to three months after he pled with Ghana’s Central Organization for Sports.

He had been accused by the referee for that match, a Senegalese, for kicking him, and refusing to avail himself when summoned to answer why he did so. Mfum denied kicking the referee, but admitted snubbing his call.

That stand-off at the Accra Sports Stadium had brought the game to a standstill, provoking the referee and his linesmen to walk off the pitch. It had taken two state ministers — Kojo Botsio and Krobo Edusei — to descend from the VIP stands in order to intervene for the game to continue.

Though he was heavily criticized by fans, administrators and press — “He is a nuisance, a disgrace to Ghana soccer…” wrote a Graphic writer, “…he has been slapping players and officials since time immemorial” — there was a feeling deep down that despite his excesses, Mfum was a necessary evil.

His 1962 ban was lifted just days after it was imposed, and the reduction of his 1963 ban from one year to three months meant Mfum would conveniently return just in time to help Ghana win the Afcon in 1963, just in time to score that goal in the tournament’s opening game.

The Ghanaian Times described Mfum as “the problem child of Ghana soccer”, but also compared his combination of competence and controversy to the great Manchester United striker Denis Law, winner of the 1964 Ballon d’Or.

All goals and guts, Mfum was in a love-hate relationship with Ghana’s football fandom, but the love always outweighed the hate: They could understand that Mfum was only fiery because he had a lot of fire in his belly. “He abhors defeat,” Ohene Djan explained. “He spends every iota of strength in him and employs all subtle tricks to convert defeat into victory.”

No wonder Djan, citing Mfum’s “drive and enthusiasm”, would later appoint him as captain of the Black Stars in August 1965, after the team was dissolved and re-constituted ahead of the 1965 Afcon. Mfum’s will to win was clearly an asset for Djan’s ambition to assert Ghana’s influence as “a showpiece on the African continent”.

The appointment was further evidence of Mfum’s importance despite his enigmatic and eccentric behaviour. Mfum had been up against Charles Addo Odametey, his colleague ‘senior-player’ who had also been a founding member of the Black Stars in 1959.

Getting the nod over Odametey was a surprising outcome for many reasons. Odametey had been a strong favourite not only because he had “more affable manners”, as the press observed, but also because he was the captain of Real Republikans, the state-sponsored “model club” established by Kwame Nkrumah and ran largely by Djan through the Central Organization for Sports.

Real Republikans, essentially a national team at club level, had been sworn enemies of Asante Kotoko, which Mfum captained, because Djan had poached Kotoko’s two best players in Baba Yara and Dogo Moro in forming Republikans in 1961. Asante Kotoko had even been briefly “outlawed” by Djan for their protests against the formation of Republikans.

Ironically, Mfum, who had been banned twice for bad behaviour against Republikans, thus making him the poster-boy of Asante Kotoko’s dissent against Djan and his Central Organization for Sports, had still managed to be appointed national captain.

Indeed, the press believed it was Mfum’s “unconquerable spirit” that swung the pendulum of captaincy in his favour despite the limitations of his disciplinary track record and the tense club politics that existed between Republikans and Kotoko.

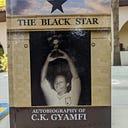

Mfum thus took an oath of office and became the foremost Black Star, joining a list of elite predecessors that included C.K Gyamfi, Baba Yara and Edward Aggrey Fynn, the latter being the captain who had lifted the 1963 Afcon, and whose playing career had been truncated by an ear injury suffered after a car accident.

By the cruel design of destiny, Mfum unfortunately missed the chance to lift the Afcon due to an injury too: A nagging knee problem reared its head just a week to the 1965 tournament in Tunisia, which robbed him of the chance of flying with the team as they went on to complete a successful title defence.

Due to his importance to Kotoko — “the real force behind the Fabulous Club’s ascendency,” wrote Djan — their coach, Hungarian Josef Ember, facilitated Mfum’s transport to Budapest for physiotherapy.

After his recovery, he returned with a bang: He helped Asante Kotoko into the final of the 1967 Africa Cup, where only a misunderstanding after two drawn games against TP Englebert resulted in the Porcupine Warriors missing out on the trophy. Mfum also powered the Black Stars to a runners-up finish at the 1968 Afcon in Ethiopia, and with six goals, similarly finished the tournament as runner-up in scoring.

He would later leave the shores of Ghana to play as a professional in JFK’s USA, starring for the Baltimore Bays, Philadelphia Ukrainian Nationals and New York Cosmos.

It’s been over 50 years since Mfum last put on a Black Stars shirt. Having made his debut in 1958, a year after Ghana’s independence, he went on to become an integral part of the team for a decade, winning the 1963 Afcon and playing at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics — eventually finishing his national service just two matches short of a century of caps.

So integral was he to the team, in fact, that at a point he was part of a cabal of players, along with the likes of Edward Acquah, Baba Yara and Edward Aggrey Fynn, known as the ‘cabinet ministers’; the team’s most powerful players.

“If you were selected for the Black Stars, it was a big honour,” Mfum tells me. “It was about love for the game and for the nation, never about money. I got to travel the world, and it was all due to the Black Stars, all due to Kwame Nkrumah and Ohene Djan.”

Globetrotting, winning trophies and getting superstar treatment were just about all Mfum gained from serving Ghana. The amateur rules of Ghana football then meant footballers had to have main jobs as their source of livelihood, leaving football as a pro bono venture. Off the pitch, Mfum worked as a stenographer and statistical clerk for state corporations.

On the eve of his departure to the US in July 1968, Mfum admitted that he had been “compelled” to take the offer from the Baltimore Bays — giving up his captaincy of both Ghana and Kotoko — because there weren’t opportunities to turn professional in Ghana. “The ambition of any footballer in most footballing countries is to turn professional one day,” he had explained.

Ken Bediako, also a former sport editor of the Daily Graphic and managing editor of the Asante Kotoko Express, explains that as part of the amateur culture, Ghanaian footballers like Mfum were not motivated by money as they “played for the love of the game and the adulation they received.” More aptly, the great Ghanaian sportswriter Kofi Badu, a mentor of Bediako, once wrote that “honour and public praise are the amateur’s prizes”.

“A whole nation paying money to watch these footballers…” Bediako further explains, “…and to give them moral support was a wonderful privilege for them.”

Unfortunately, the “wonderful privilege” Mfum enjoyed many ages ago, all the “honour and public praise” from a transient tenure of fame, have not been enough to aid his sustenance in pension. Rather, it is the rewards reaped from hard work in the land of Kennedy that has been the remedy to a potential struggle in retirement.

After his stint abroad ended in the 70s, Mfum stayed in America for many more years, getting to live the American Dream, a privilege he needed to become one of the few Ghanaian football stars from his era who now live comfortably in old age.

Today, he resides in East Legon, a suburb in Accra known for the affluence of its inhabitants. His house, a decent building by the side of a quiet street in the East Legon community called Menpɛ Asɛm (‘I do not want trouble’), is named “Mary Mfum’s Villa”, in honour of his late wife. He is surrounded by family, and has a driver who chauffeurs him around, especially to attend funerals in Hwediem, his hometown in the Ahafo Region, many miles north of Accra.

In an interview with journalist Saddick Adams last year, Mfum worried about Ghana’s decline since the promising socio-economic conditions of the early years after independence, which he got to experience.

“Your generation really does well with surviving in these current conditions,” he said. “Our leaders [over the years] have really ruined the nation.”

“I sometimes sit to reminisce, and think: ‘Ei, if I hadn’t been to America, how would my life had turned out?’” he added. “If I hadn’t lived in America, I wouldn’t have known how bad things are here. [I suspect] the money I receive in pension is like that of an MP’s salary. Sometimes when I finish eating, I just declare: God bless America.”

God bless America?

“An American has the mentality to die for his nation,” he explained. “I’m sometimes tempted to think it is does not pay to die for this nation, because when you are killing yourself out of patriotism, someone is benefitting, and this person’s corruption goes unpunished.”

These days, apart from occasional cultural references to Mfum atete net, not many know who Wilberforce Mfum is, and not much is known about his storied career. He is rarely recognized when he steps out — he recounts attending an Asante Kotoko game recently and barely being acknowledged, until someone, 30 minutes to fulltime, went to reveal his identity to the stadium announcer.

But there have been some moments of recognition in recent years, albeit few and far between. In 2006, he was briefly brought into the limelight with a Grand Medal, a national decoration conferred by then Ghana President J.A Kufuor — himself a former Asante Kotoko chairman, a club with whom Mfum won five league titles and three FA Cups.

In 2014, Mfum’s name was one of many that surfaced when the government of President John Mahama doled out $540,000 to be shared amongst the four generations of Afcon winning Black Stars squads. That gesture was geared towards gratifying the Ghana groups of 1963, 1965, 1978 and 1982, to heal the hurt of unfulfilled promises by governments over the years.

Last year, Ghana President Nana Akufo Addo, while at an event as part of a tour of the Ahafo Region, stopped to interact with Mfum, who was amidst a crowd of people waiting to greet the President. Akufo-Addo beamed as he exchanged pleasantries with Mfum, and not only did the duo share a firm handshake, they laughed and talked and hugged, with the familiar warmth typical of a long-time reunion.

Indeed, during the early to mid 60’s, a period a young Akufo-Addo spent studying at the University of Ghana following his return from the UK, Mfum was one of the national stars of the time. The President, a football lover, seemed excited to see one of his heroes.

With what seemed like the impulsive and impatient joy of nostalgia, Akufo-Addo introduced Mfum to a member of his entourage, as if to say: “Do you know this man? This is the great Wilberforce Mfum!”

“Oh really? As in Mfum Atete net?”

“Yes, that’s him!”

A few months after that heart-warming incident, the Ghana Football Awards honoured the founding members of the Black Stars — of which Mfum is one of two surviving members along with Dogo Moro — on the team’s 60th anniversary.

Most Ghanaians living today remain oblivious of their football stars from the 50s and 60s — the architects behind the foundation upon which this country’s football reputation is built, men whose sacrifices bought bragging rights still in use today.

Apart from a select few who have been immortalized by the naming of monuments after them — or in Mfum’s case, the prevalence of myths about them — the rest have had their names and exploits lost in history, trapped in the pages of old newspapers, probably never to be discovered due to the poor culture of research a reading. Due to poor archiving, the country today has neither a sports museum nor library to preserve their legacy.

Mfum is disappointed in the Ghanaian attitude to national heroes: The failure to acknowledge them at worst and to celebrate them at best. He calls it “systematic”, something he has come to accept.

“We are not celebrated, but it does not worry some of us,” he said, his tone betraying his words.

“Many of my mates have died and gone. When Asebi Boakye, a great Kotoko captain, died recently, I had to frustratingly lobby the club before they could make a paltry donation. When James Adjaye died, it was the same thing. James Adjaye was the best number ten player in the whole of Ghana!”

Mfum turns 85 in August next year, and regular trips for funerals are only reminders of the imminence of the inevitable.

“We’ve played our part,” he said. “Maybe if they recognized us before we died, that’d be great. But if not…”

He shrugged.

“If I died and they honoured me, I would be very happy, but I would also be gone.”