Ghana. Baba Yara. Football.

Fiifi Anaman tells the tragic tale of Baba Yara, the man who many believe was the greatest Ghanaian footballer of all-time.

August 14, 1963 — The arrival

The massive crowd at the Accra Airport, from all walks of life, excited and expectant, had to be cleared off the tarmac.

They had risked trespassing on to the tarmac — better still, overflowing on to the tarmac — because they wanted to be in close proximity with what was about to happen. They were waiting for a BOAC plane to touch down. The plane was coming from the UK.

There was one particular passenger they had come to jubilantly welcome. They had come to see him, that beloved football superstar. They had missed him. Terribly.

The superstar had left Ghana about five months earlier on a stretcher, and it was expected that he was going to come back home on his feet.

Why?

He had been sent to the UK for medical treatment at the National Spinal Injury Center at Stoke Mandeville Hospital after sustaining a spinal injury. His injury had occurred after a tragic motor accident on March 24, 1963.

Five days after the injury, he had been flown to the UK, seen off by a large crowd — teammates, officials and fans. Indeed, the crowd that had been at his departure could rival this crowd that was now looking forward to his arrival.

While in the UK, a spokesman for the Ghana High Commission in London had reported to anxious football fans back home that their injured star was “making steady progress” from his spinal injury, and that he could even now “move his limbs”.

On July 8, 1963, amidst growing worry amongst fans and sympathizers, Ohene Djan, Ghana’s powerful Director of Sports, the head of the Central Organization for Sports (COS), travelled to the UK to do a “critical study” on the injured football star’s condition.

Djan promised to eventually report back to the injured star’s well-wishers. Accompanying Djan on the trip was prolific goal machine Edward Acquah; the injured star’s longtime teammate at club and national level.

Acquah was not only a friend of the injured star, but a beneficiary of his prowess on the pitch– most of Acquah’s goals were assisted by the injured star, ever the provider, ever unselfish.

On their return home, Djan confidently calmed both the public and the press. The injured star would triumphantly return home soon, in good health, he said.

Now, that soon had finally come.

At the airport, the BOAC plane eventually arrived, descending diagonally, kissing the tarmac. It circled its way to where the passengers could disembark.

A wide variety of people, men and women, black and white, young and old, came down the gangway.

With every passing passenger, the crowd waited patiently for the man they had come to see. There was tense anticipation.

“We had pictured him emerging from the plane, on his feet again, waving a white handkerchief,” says Ken Bediako, who was then a young reporter for the Daily Graphic, and who was amidst the crowd that fateful day.

More passengers got down, yet there were still no signs of the man, their hero. Surely, he would be the last to come down, they thought. Saving the best for last — the classic arrival.

After all, such a climax would be a sight to behold, a story to be told.

Suddenly, the crowd heard sirens blaring. An ambulance was making its way to the foot of the gangway.

The crowd became nervous, wondering what was happening.

Then they saw him, the injured star, the great Osman Seidu Maada.

Maada was not on his feet like everyone expected. He was on a stretcher, again.

The man, who was affectionately called Baba Yara by all, was being carried down the gangway, in preparation to be eased into the ambulance.

That was all the crowd could see — a heartbreaking sight. This couldn’t be right.

They were dumbfounded. Discombobulated. Distraught.

“It was a big disappointment,” says Bediako.

An anti-climax, too.

“The airport turned into a graveside,” Daily Graphic writer Charles Asante wrote.

“Tears run down every cheek.”

Note:

I was inspired to write a profile on the great Baba Yara not only because he had a tragic story, or that I watched the moving documentary done on him by my senior colleague, the excellent Saddick Adams.

I wrote this because of my maternal grandmother.

My granny, Dorothy Ama Osei, née Mensah, was a fascinating old lady who took particular interest in my obsession with football as a young boy.

At her home in Kumasi, where I lived for most of my formative years, I would play football alone in front of the house, in a space directly opposite a corridor where she used to sit, quietly, perhaps reflecting on life.

Anytime I hit the ball against the wall, ‘Auntie’, as we affectionately called her, would either smile when the impact was mild, or scold me when it was loud.

One day, upon striking the ball ballistically against the wall, behind which she sat, she exclaimed, “Ei, Baba Yara!”

The name stuck in my head. From then on, anytime she saw me, she would call me “Baba Yara”. Of course, I never knew who Yara was. But I would find out many years later.

On the eve of the 60th anniversary of the accident that incapacitated Baba Yara, this piece is deservedly dedicated to Auntie, who died thirteen years ago, and of course, to Yara himself — who was born ten years after Auntie.

May they both rest in perfect peace.

October 12, 1936 — In the beginning…

Baba Yara was born right at the geographical center of Ghana.

In the modest settlement of Kintampo Zongo, Yara was born to Amina Ibrahim.

He was later named Osman Seidu Maada, after his father, Seidu Maada, and his uncle, who was named Osman.

So, why Baba Yara?

“We couldn’t call him Osman because that was also the name of our senior uncle,” Yara’s brother, Awudu Maada, told Saddick Adams.

“So as children, in order to differentiate, we decided to call him Osman ‘Baba’ (father). Our mother, who would hear us call him Baba, started to tease him: ‘Ei, all the kids call you Baba, so you are nkwadaa papa (the father of kids).

“That is how come he came to be called Baba Yara.”

In Kumasi, Ghana’s second largest city, the sports stadium, Ghana’s biggest, is named after Baba Yara.

The stadium is many people’s introduction to the name Baba Yara…then it ends there.

Few people know why the stadium is named after him, or more importantly, who the man was.

Baba Yara’s story is “too well known to be retold,” an Asante Kotoko official once said.

This was in 1969.

But, in 2023, it needs retelling. No?

Let’s go.

As you know now, Baba Yara was not born in Kumasi. Neither was he bred there. But the city became his adopted home sometime in his formative years.

Baba Yara knew and loved football early in his life, and in Kintampo, would sneak out of class in Islamic school (Makaranta) to go and watch people play.

On his return, he would practice all the things he had seen on the field, with the aid of an orange as a ball.

His truancy made his father concerned, prompting him to take action.

That action would turn out to be a transfer of young Yara to Kumasi.

As Awudu Maada explains, an older sister of theirs was then living in Kumasi. This was after a man, a Mallam and Islamic scholar, had come to whisk her away from Kintampo with marriage.

Yara’s father sent him to Kumasi to go and live with his sister, and to understudy his brother-in-law. It was his father’s hope that Yara would switch from football to academics.

Well, that didn’t quite happen.

Yara continued to play football, and soon went from oranges to leather balls.

He played for colts (youth) clubs in Kumasi such as Zongo Corners, Rock of Ages and Red Lions.

He excelled.

But his love for football would be punctuated by a second love: horse racing

In his teens, Yara became a horse racing jockey, dazzling race goers with his skill on the saddle. “He was part of the pioneers of the Race Course in Kumasi,” says Dogo Moro, Yara’s close friend and teammate during his football playing days.

Yara’s mastery of jockeying perhaps owed to the fact that he had also been a great cyclist. In his early days at Yalewa Zongo, close to Asawase, Kumasi, he used to entertain kids and adults alike with his showmanship in riding bicycles.

But he was always going to return to his first love.

When that time came, an acquaintance of his, who knew of his abilities in the beautiful game, suggested that Yara join Asante Kotoko, the biggest club in Kumasi, and indeed, one of the biggest nationwide.

Yara, unsurprisingly, didn’t find it hard getting into the fold of the Porcupine Warriors, as Kotoko is known.

Kotoko, according to a prominent director of the club, “saw great promise in Yara.”

He was just too good.

May 5, 1969 — The call: Part I

In the office of the Daily Graphic’s sports department, J.K Addo Twum, editor, and his assistant, Ken Bediako, were working, as usual.

It was a normal day.

Then the phone rang. It was 10.10 am. Ken Bediako picked the call. “Graphic Sports,” he announced.

On the other end of the line was Mr. L.T.K Caeser, Ghana’s Deputy Director of Sports. He had a message to relay. And he was precise about it.

There were four chilling words: “Baba Yara is dead.”

Addo Twum couldn’t believe the news. “Is Baba Yara really dead?” he questioned.

Surely, that couldn’t be true. Baba Yara, who was only 33? How?

Addo Twum quickly rushed to Kanda Estate, where Baba Yara lived.

There, he met Yara’s brother, who sadly confirmed the news.

So it was true. The King of Wingers was gone. Forever.

“What a shock!” Addo Twum would later write.

March 24, 1963 — Aw, Kwame Siaw! Part I

Wait, was Kwame Siaw really drunk that fateful day?

“He was drunk,” Dodoo Ankrah simply says. “He had taken in something.”

Ankrah’s answer is very assured. No speculation. No suspicion. Just plain and cold: He. Was. Drunk.

Kofi Pare is more diplomatic. “I wouldn’t say he was a drunkard,” he says. “A drunkard wouldn’t be able to drive, or?”

Hang on. There’s a but…

“But I must admit we all knew that he loved to take one or two.”

Okay, so that’s now established. Take note of this — because this is a very important detail in this tale.

Now, let’s get on with the story.

So, who was Kwame Siaw?

Driver. He was a driver. He drove the Sports Council Benz bus that conveyed the famous and infamous club Real Republikans to and from games.

Famous and Infamous? Yes. You’ll find out later.

Now, back to the story. Edward Dodoo Ankrah and Lawrence Kofi Pare, goalkeeper and striker respectively, were prominent footballers in the 1960s.

Ankrah was nicknamed “Magic Hands”. Pare was nicknamed Kopa (KOfi PAre), a name he got from Real Madrid and France legend Raymond Kopa.

Both were part of an elite group of footballers in the country who played for Real Republikans.

Now let’s dive into a necessary but long back story.

OOC? Oh I see…

Real Republikans was what you’d call a super club, or a ‘model club’, as its founder, Ghana President Dr. Kwame “Osagyefo” Nkrumah, called it.

It was set-up by Ohene Djan, on the “instructions of the Osagyefo”, in 1961.

The idea was to have a club where the country’s best footballers could play together, so as to make them develop a familiarity with each other.

This was done to favour the national team, the Black Stars, because the COS and the Ghana Amateur Football Association (GAFA) used to have issues when inviting players into the national team.

The clubs and employers of the players would sometimes play hard ball in releasing the players, and when they finally did, the players — because they came from different clubs — didn’t play with enough chemistry and telepathy, because they didn’t know each other well. They hadn’t stayed together long enough.

And so Republikans — named after Real Madrid, the most popular, most successful global team of that era — was set up in the first quarter of 1961 to be a shadow national team. A ‘national club’, if you will. The players were going to stay together, play together.

They were also to, according to Nkrumah, “offer leadership and inspiration to football clubs in the country.”

If Republikans was going to be a quasi-national team, it had to have the nation’s crème de la crème. The problem was that such stars were scattered all over the country — in Accra, in Kumasi, in Sekondi and in Cape Coast. And they already had clubs too.

Hmm.

But that was no problem for Djan. He would basically use Nkrumah’s backing as a license to raid all the top clubs for their best players.

At Kotoko, the two biggest stars were their captain, the brilliant Baba Yara, and Dogo Moro, their dependable defender.

Yara and Moro were not only the stars of the Porcupine Warriors, they were also the best of friends. They had things in common. They were both from Kintampo. They were both light-skinned.

For some, they even looked like each other.

“People said we were twins,” says Dogo Moro, laughing.

“He was my brother. We did everything together. We were roommates during club and national assignments. We loved each other. I loved him.”

Djan was going to build the Republikans — nicknamed Osagyefo’s Own Club (OOC) — around these two, and so they had to leave Kotoko, by hook or crook.

This sparked an ugly tug of war, and here’s why.

Kotoko was known to be a proud and powerful club. They were owned by the monarch of the Ashanti people, the ‘Asantehene’, Otumfour Sir Agyemang Prempeh II.

They were the “idol club of Ashanti”, and in those years, anything Ashanti was estranged from anything central government.

In the 1950s, the National Liberation Movement (NLM), a political party formed by the Asantehene’s chief linguist, Baffour Akoto, opposed the central government of Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party (CPP), so much that they advocated for yate yɛnho, to wit, ‘We have severed ourselves’ (from the central government).

Although unofficial, the NLM was known to represent the interest and aspirations of Ashantis.

Indeed, the Ashanti Kingdom was not only one of the most powerful kingdoms in Africa, but in the world. The NLM wanted decentralization because they felt the Ashanti kingdom was influential enough to be on their own, to be their own nation.

And so they fueled this desire by resisting Nkrumah’s unitory national government, lobbying for Ghana to become a federation, so they could acquire a semblance of autonomy.

In those years, the war between the NLM and the CPP wasn’t only political and ideological, it was also physical. There were many bloody, even fatal clashes between both parties.

Interestingly, the NLM was not the only Ashanti body that projected and protected Ashanti interests, in the process displaying a disdain for the center.

There were more Ashanti separatist examples.

For most of the 50s, the Ashanti Football Association, dominated by Kotoko’s top brass, was constantly at loggerheads with the national body, the GAFA. So much so that Ashanti clubs would boycott the national league, or bar its players from joining the national team for assignments.

Indeed, take the scope further back, and zoom out of football, and you’ll discover that in colonial era, the Ashantis never agreed with the English, who constituted the central colonial government. This resulted in the fierce, frequent Anglo-Ashanti wars that took place between 1823 and 1900.

Kotoko, who “didn’t see eye to eye” (Moro) with Djan, were so against Republikans that they threatened to boycott the 1961/62 league season.

Fascinatingly, Djan was a Kotoko fan, a faaabulous! man through and through, but when it came to work, it was serious business. His heart never ruled his head.

And so he banned Kotoko from the league for what he considered pure petulance. “At this stage of our development in sports, discipline is important indeed,” Djan roared.

Kotoko would eventually agree to play in the league, albeit reluctantly, but the bad blood had been established and entrenched.

When it came to the orchestra that was OOC, Nkrumah seemed to be the composer, with Djan being the conductor. A figure head and an effective head. It was Nkrumah’s idea, but Djan was the man on the ground who did all the work, who fought all the battles, out of loyalty to Nkrumah and to the nation.

As for Nkrumah, he expected that the Republikans idea was going to experience a pushback from power players in Ashanti, and for him, the repulsion of his national agenda bordered on treason. He felt they didn’t have the nation’s interests at heart, that they cared more about their parochial interests than the nation’s larger interest.

Republikans played the 1961/62 Ghana league season, their first, on a non-competitive basis. They played matches, but weren’t accorded points or credited with wins.

In the 1962/63 season, when it was decided that they would compete, they proved better than every other team in Ghana, winning the league title.

They did this despite suffering what Djan described as “the greatest club catastrophe in Ghana history.” (You’ll learn about this catastrophe later).

The team won a record four consecutive Ghana FA Cup titles from 1962 to 1965. They were also semi-finalists at the Africa Cup of Champions Clubs, today known as the CAF Champions League, in 1964. Nkrumah had advocated for the establishment of that tournament, and the first edition had been hosted in Ghana, with a trophy donated by Nkrumah himself.

At the height of their powers, the form of Republikans reflected on the form of the Black Stars, as the national team won back-to-back Africa Cup titles in 1963 and 1965.

When the team was disbanded after the coup that deposed Nkrumah in 1966, it would take the Black Stars 12 long years before winning another trophy.

Alright, enough of the history lessons.

Kotoko just didn’t want to give up Baba Yara, their skipper and star, and Dogo Moro, their darling defender. At least, they weren’t going to give them up without a fight.

But, how did the players feel?

“Who didn’t want to join Republikans?” Dogo Moro asks.

Well, true.

Ohene Djan made sure that OOC players were treated as the national ambassadors that they were. They became national celebrities. Afterall, the team was for the government. It was for the State. More importantly, it was for Kwame Nkrumah.

Djan secured lucrative jobs for the players at prominent state institutions like the Farmer’s Council, Workers Brigade and Sports Council. He made them the envy of many.

Republikans became Ghana football’s aristocracy. Djan prioritized the team with preferential treatment. The club was exclusive and extraordinary. One could only join after being called. No player chose them — they chose players.

Their welfare terms were so good that when Baba Yara later got injured while on duty with them, they still kept him on their books and accorded him “all the privileges and facilities extended to regular players of the club.”

“He would remain a 12th member of the club and will receive the 12th medal in all competitions,” they said. They also instituted a “special five-year financial provision” towards the maintenance of one of Yara’s two daughters.

Meanwhile, other clubs detested Republikans, and, why not? How would you feel if you work hard to groom a player for them to grow to become great, only for them to be grabbed away, just like that.

Of course, Djan tried to justify the ruinous recruitment style of his club. He said that based on “knowing the amateur rule which permits no player to bind himself with a particular club forever” he wrote letters to the players and they agreed to become members of the club.

No one forced them, he implied.

But this wasn’t entirely true.

“When you were called by Republikans, whether you liked it or not, you had to go,” says Pare, who was poached from Sekondi Eleven Wise

Here’s Djan again, in an attempt to justify OOC’s procurement process:

“Amateur rules allow for a player to ask for a transfer, upon the expiration of a contract signed for a particular season.”

You would think that having public (stylized as publik) within their name would mean Real Republikans had the support of the public?

Not quite.

There was widespread public uproar upon the formation of OOC. Afterall, fans already had the clubs they supported, and these clubs’ arms were being twisted to give up their treasured talismans.

“Why can’t Republikans be started from scratch?,” a fan questioned in a letter to the Daily Graphic. “I feel Republikans should not be formed at the expense of those clubs who sacrificed so much to see their players attain the form which is now considered to be good enough for ONLY the Republikans.”

To be fair, there were some fans who welcomed the OOC experiment.

“I was very pleased to read of the formation of the Ghana Republikans as a league club,” a fan wrote. “Because it will enable our stars to have a regular practice together and this will give the selectors much more time to watch their own practices before they are camped as Black Stars.”

That nonetheless, Republikans were usually jeered rather than cheered at the various match venues. For the players, it was a bitter sweet experience — playing for the club came with a lot of hate, but there were a lot of highs too. A double-edged sword.

In the end, after all then polarizing politics, after all the draining drama, Djan prevailed. Yara and Moro eventually became foundation members of Real Republikans — the core around which the inaugural team was built.

“Djan was really fond of us,” Moro says.

While at the club, Yara and Moro signed a document that said that they were “proud to serve the needs of the Ghana national team more effectively and more constructively” through Republikans, adding further that they felt that the controversy surrounding their poaching was “unnecessary”.

Kotoko became bitter. Water was wet.

“We told them (Yara and Moro) not to go.”

This is striker Wilberforce “Bulldozer” Mfum, who was then also a star at Kotoko and the national team.

But they went, and one of them was destined not to return.

March 29, 1963 — The departure

He was leaving. Baba Yara was leaving for the UK.

Treatment at the 37 Military Hospital had gone well, but the facility did not quite have what it took to fully deal with Yara’s spine issue.

While at the hospital, Yara was his usual optimistic self. He looked “cheerful” and “hopeful”, according to a report.

“I am a bit okay,” he said, adding that he looked forward to returning to the field soon.

His courage was admirable. Of course, at 27, this was a man who still had a lot of football to look forward to. But this was also a man who had barely been able to move his limbs since the accident.

Meanwhile, messages of sympathy and solidarity had come in from all quarters of society not only for Yara, but for his club OOC, whose bus had been involved in the motor accident that had led to Yara’s spine injury. This motor accident is what Djan referred to as a “catastrophe” earlier.

Suddenly, Republikans had gone from being hated to being loved.

Well, it was more of pity — but, who cares?

Hearts of Oak chairman H.P Nyemetei urged all clubs in the country to show affection towards OOC. “Cheer them on and make them feel comfortable in their moment of affliction,” he said. “And do remember that this predicament can happen to any club at any time.”

Meanwhile, Republikans themselves were in deep mourning, but if a statement they released in the aftermath of the accident was anything to go by, then they were as defiant as their star Baba Yara.

“Though much is taken, much abideth,” they said.

The statement in full: “With bruises on our faces and with limbs and heads in plaster, we are resolved more than ever to keep the Republikan flag flying high in the national league. The loss is great and the effect demoralizing, but surviving teams at both regular and reserve levels are being built around the few players who escaped with life and limb.

“Players from our third and fourth generations imbued with the true Republikan spirit have gallantly answered to the emergency. The survivors will not let the faithful friends of Real Republikans down. Now may we appeal to all true lovers of Ghana soccer to share our affliction with us and to join us in prayers for the speedy recovery of the injured players who are now at the 37 Hospital.”

Interesting fact: Despite the tragedy crippling the team, OOC would go on to pip Kotoko to the league title at the end of that season.

“With broken limbs and bruised, bandaged arms and legs”, they “determinedly and heroically” strode on to the title, as Djan wrote.

So, back to March 29.

Baba Yara was about to be flown to London, to receive treatment at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital. The trip was being sponsored by the COS and Real Republikans.

Here’s an eerie irony: shortly before the accident, Baba Yara had been voted the “best dressed gentleman” at a competition organized at La Ronde, a popular night club in Accra. The prize for that competition was an all-expenses paid trip to the UK.

Baba Yara was thus originally scheduled to go to the UK for a three-month tour. Yet here he was, going to the UK on a stretcher.

La Ronde, however, did not forget Yara. Their manager, Mr. Habib Ghanem, who returned from a tour of Europe to hear of Yara’s predicament, said he was willing to transfer the return ticket won by Yara to his dear wife, Patience. He said he was even willing to give Patience 25 pounds of pocket money.

“I am doing this in the hope that Yara may have the comfort of his wife when he is away from home,” he said. “It is also my fervent prayer that Yara recovers soon.”

This gesture — described by Patience as “wonderful, kind and nice” — was also timely: the medical authorities had recommended that Yara be accompanied by his wife to the UK as her presence would “enhance his speedy recovery.”

When it was time for Yara to leave, he was accompanied by his wife, Patience, and Dr. R.O Addai, a medical officer at the 37 Military Hospital.

Before he flew out, Yara met Edward Acquah, Edward Aggrey Fynn and Charles Addo Odametey — three of OOC’s senior players.

“My heart is still there with you,” Yara told them. “If I have unknowingly offended you, please forgive me and pray for my speedy recovery.”

“We vowed to remain and die with the model club,” he continued. “I will follow your fortunes in the league with interest and each victory registered by you will hasten my recovery.”

Yara must have smiled when he heard in the UK that not only had Republikans won the league, they had also won the FA Cup too — a historic double, the first in Ghana’s football history.

March 24, 1963 — Aw, Kwame Siaw! Part II

Alright, we’re back to Kwame Siaw, remember him?

He was behind the wheel on this day when Real Republikans were scheduled to play Volta Heroes as part of the 1962/63 Ghana league season.

The match was to take place in Kpando, in the Volta Region. It was a Sunday.

To understand what was going to happen next, we need to take a trip back two years.

1959.

That year, 650 people died, and 6000 got injured, from road accidents in Ghana. This was according to the Ministry of Interior.

On top of the Ministry’s list of accident causes was drunkenness. Further down the list, there was carelessness and there was over speeding.

Right.

Now back again to Kwame Siaw, who was driving the Republikans to Kpando.

Mind you, he already has drunkenness down pat.

One down, two to go.

Those were the days of right-hand driving in Ghana.

On the trip to Kpando, Kofi Pare was seated to the left of Siaw on the front row. Pare was to the extreme left, such that he was seated by the window. In the middle of Siaw and Pare was Agyemang Gyau, an attacker who was as potent as Pare.

On the trip to Kpando, Siaw ticked the second box on the Ministry of Interior’s list mentioned above. He was over-speeding.

Pare remembers the speeding being so severe that most other players in the bus began to complain loudly.

“Siaw didn’t know the road,” Pare recalls. “No one knew the road.”

There were times when the players would shout to alert Siaw that the bus had to negotiate a curve slowly and not speedily. “Yɛɛbu curve! yɛɛbu curve! (We’re turning! We’re turning!)” some players would shout.

Yet Siaw would barely budge.

Pare, who was also an experienced driver then, began to worry about the way Siaw was assaulting the accelerator. He wanted to reprimand Siaw.

But Siaw was many years older than him. In fact, Siaw was older than all the 17 players in the 23-seater Benz bus. Also, out of courtesy, Pare didn’t want to accost his kinsman.

Both Pare and Siaw were of the Akuapim tribe, from the Eastern Regional town of Aburi. This is coincidentally also where Ohene Djan hailed from. Yes — the same Ohene Djan who co-founded and ran Real Republikans. In those years, Akuapims were called Home Boys.

Djan, according to those who knew him, loved his Home Boys, favouring them.

Mmm. Maybe that was why Siaw was a driver for the team then. Perhaps that was also why Kofi Pare — although very talented — was also in the mix.

Infact, the family houses of Djan and Pare were close to each other in Aburi, as Pare confesses.

Meanwhile, in the bus, Pare had to find a nice way of telling Siaw to dial down the speed.

So he turned to the man who was seated behind him for help.

That man was Baba Yara.

Yara was relaxed in his seat, seemingly unbothered, despite the concern that was sweeping across the bus. “He was always smiling and laughing,” Pare remembers. “Nothing seemed to bother him.”

Pare reported Siaw to Yara, because Yara was the senior-most member of the players seated in the bus. All the other OOC senior players — Charles Addo Odametey, Edward Aggrey Fynn, Edward Acquah, Ben Acheampong and Franklin Crentsil — had travelled separately in a car belonging to Edward Acquah.

Yara was thus holding the forte of seniority in the bus, and now, after having received Pare’s complaint, he decided to talk to Siaw on behalf of his teammates.

Typical of Yara, there was no confrontation or reprimand, just a friendly caution. He called out Siaw’s nickname. “Please take your time,” he simply said.

A skillful massage. A simple message

“There! I’ve told him!” Yara said to his teammates, jokingly. “Now you can leave him alone!”

Surprisingly, Siaw didn’t quite ease or cease the speed, though he managed to reach Kpando safely.

The game itself turned out to be easy for OOC.

Volta Heroes, playing in the league for the first time, were bottom of the table.

They stood no chance.

They conceded five goals.

Where was Dogo Moro, and why wasn’t he with the Republikans now? Well, amidst threats and pressure from Kotoko, he gave in and went back to the Porcupine Warriors after one season.

Betraying Ohene Djan came with career-changing consequences, as Djan made sure Moro was never invited to the Black Stars camp again.

Meanwhile, Moro remembers an interesting detail. At this point, it’s a revelation. He claims that Baba Yara had confided in him that the Volta Heroes match was going to be his last match for OOC. “After that,” Moro claims, “he was planning on returning to Kotoko.”

Little did Baba Yara know that not only was it going to be the last game he would ever play for Republikans, but the last game he would ever play in his life.

On Republikans’ return journey from the venue, it began to drizzle. Then rain.

The road became slippery.

These were conditions that called for slow, careful driving.

But Kwame Siaw was behind the wheel. The same Kwame Siaw who liked to “take one or two”.

In fact, Pare suspected that Siaw had had a few drinks at the game. “I mean, it was a game,” Pare says. “People drink at games all the time. It’s a side attraction. Knowing him, I suspected he had had one or two as usual.”

Dodoo Ankrah: “He was drunk!”

And so the over speeding continued. Pare, seated close to Siaw and witnessing things first hand, became the most worried of all the players on the bus. As Siaw continued to drive dangerously, he got scared and infuriated.

He got so jittery that he got up from his seat and descended the mini staircase that was at the exit door of the bus. It was as if he was ready to open the door and jump out in case Siaw accelerated them into an accident.

Then, at a T junction in a town called Kpeve, Siaw, by this time speeding beyond belief, turned to the right spontaneously, without stopping at the main road to look if there was an oncoming vehicle.

Close shave.

At this point, the notorious driver was being plain irresponsible.

“It was carelessness,” Pare says.

Carelessness? Remember the Ministry of Interior’s list?

Third box ticked. Three out of three now.

Trouble.

It was only a matter of time until tragedy struck. Pare knew it, and so he stayed rooted to his spot on the staircase. He had readied himself for the worse.

About a mile later, at an L junction, Siaw messed up the negotiation of the curve to the left, thanks to the sheer speed at which he was travelling.

He lost control.

Helplessly, the bus skidded across the road to the other lane, and then past it, right into a ditch which was about 10 feet into the ground.

“The car didn’t crash into the ditch,” Pare says. “It didn’t capsize either,” he adds, “It landed horizontally! With such force!”

The impact of the landing, as expected, was almost fatal. Pare remembers immediately and impulsively reaching for the door, opening it and jumping out.

He did it so quickly that a stick — or was it a stone? He can’t quite remember — cut his left knee upon landing awkwardly in the bush.

Meanwhile, the landing had wreaked havoc inside the bus.

Seats had broken. Legs and hands had broken.

Right by the ditch was a market. By the time of the accident, around six in the evening, the market had almost emptied, with many traders having closed.

“We were lucky they had closed,” Pare says. “The way the bus skidded, we could have hit someone and killed them. That would have been another problem.”

There was a woman, as per Ankrah’s recollection, who had been an eye witness of the accident. Perhaps a market woman, she was so shaken by the sight that she started exclaiming, almost wailing. “M’awu oo, M’awu!” (I am dead ooo! I am dead!)

The few people left at the market heard her and rushed to the scene. By this time, there was pandemonium and panic, with the players bellowing out their injuries, a roll call of pain. “My head! “My neck” “My leg! “My chest!”

Some of the men among those who had come from the market, recognized it was the Real Republikans team, and started calling out the names of their favourite players to see if they were alright or needed help.

Some of the players who had made it out of the bus with minor injuries and bruises also called out the names of their colleagues, desperate to hear a response. They wanted to check if everyone was alright.

“I remember calling out for my brother,” Ankrah says.

His brother was Abeka Ankrah, a young student who had only just been drafted into OOC.

Abeka had broken his left leg and had to be carried from the bus.

After a while of calling out names, it became obvious.

He was the only one who was still missing. His was the last name standing — everyone called out his name, but there was still no response.

Baba Yara! Baba! Baba!

Rewind: Yara was seated behind Pare’s seat. His seat was just by the exit door, where Pare had descended the stairs to stand beside.

At the moment the bus brutally bounced, it threw everyone forward, such that Baba Yara was pushed from his seat, eventually crashing into Pare’s vacated seat, which in turn smashed the windscreen under the weight of Yara’s body.

As it turned out, Yara ended up falling and getting stuck under one of the seats.

“I saw a lot of people (both the good Samaritans and the players) trying to pull Baba out of the bus.,” Ankrah remembers. “They were pulling him so hard that I felt sorry for him and worried about him.”

Eventually, Baba Yara was successfully pulled out of the bus. But at a cost. He had made it out, but he was down and out.

Unlike anyone else who had suffered a serious injury, Yara lay flat on his back and could barely utter a word.

It was getting dark, and there were no cars on the road. It took about an hour before a cargo truck drove by. For that hour or so, no one heard Baba Yara speak.

He lay down motionless and speechless.

The folks in the cargo truck were kind to empty the things in the truck so they could load their truck with the seriously injured players.

There were about six players in all who needed urgent treatment. Baba Yara, as it looked, was top of the list. Apart from Abeka Ankrah who had broken his leg, the likes of Agyemang Gyau, who sat by Pare, had broken his hand.

Kofi Pare was mistakenly added to the list of seriously injured players. “I found myself joining the truck as everyone thought I had been seriously hurt,” he says. “But in truth, I wasn’t. It was just the cut on my knee. I didn’t say a word about it though. I just went along with it.”

In the bucket of the truck, Pare remembers being beside Baba Yara, who had been carried and eased unto the floor of the bucket on his back. It was only on the bus that Yara started to speak.

“Sɛ yɛse yɛbɔ bɔl, anaa? Bɔl diɛ ɛtumi ba saa, nti ɛnyɛ hwee,” he whispered to Pare. (“We claim to be footballers, don’t we? Things like this happen in football, so it’s nothing”).

Pare was both encouraged and heartbroken at the same time.

Once the truck reached a hill, the engine went off, and the truck began to reverse. Pare remembers jumping out the bucket, scared. But the retreat was short lived.

The truck, though, couldn’t move again. It had to take the arrival of another bus to finally take them to their destination: the Ho Hospital.

It was late in the night, but the stars were able to receive treatment, at least first aid treatment.

Meanwhile, news had reached Accra. Nkrumah’s boys had been involved in an accident and most of the players were in distress.

Immediately, an Air Force helicopter was deployed to Ho to go pick up Yara and co. Djan said the Air Force had been “prompt and patriotic” by coming to the aid of OOC.

The helicopter arrived at the Accra airport, where the five seriously injured footballers — with the slightly injured Pare being the sixth — were taken to the 37 Military Hospital.

Meanwhile, a land rover was sent to go pick up the remaining members of the squad who had had slight injuries.

Upon arriving in Accra, most of these players reportedly collapsed — now succumbing to the impact of the bus landing which seemed to have been suppressed in the immediate aftermath of the accident.

The players — including Dodoo Ankrah — were all taken to the Korle Bu hospital for checks.

The next morning, most of the players who had been taken to Korle Bu were discharged. Ankrah, who had been seated behind Baba Yara on the bus that fateful day, remembers being so traumatized.

“Because of what happened, every March is sentimental for me,” he says. “I celebrate my birthday on the 8th, and then on the 24th, I remember the accident and become very sad.”

Ankrah, now 89, goes on to make an interesting observation:

“This is something strange that happened: all of the players who travelled privately from Kpando to Accra all went on to have individual accidents in the ensuing years,” he says.

“Of course, people ascribed superstition to it. But I don’t know. What happened, happened.”

Over at the 37 Military hospital, only Kofi Pare was unsurprisingly discharged the next morning.

Mind you, there were six of them. Pare was out. So five left.

It was reported that four of them were doing well.

Four? What about the fifth?

Baba Yara.

Oh no.

October 29, 1955 — The day before showtime

It was the day before the D-day; the big game.

It was a Saturday, on the eve of the 1955 Jalco Cup on Sunday— the fourth edition of the coveted Cup series.

In the 1950s, the Jalco Cup, a stocky trophy donated by a company called Jo Allen and Co — was all that mattered.

Forget everything else — this was it. The real deal. The bone of contention. The holy grail.

It was played between the Gold Coast (as Ghana was then known) and Nigeria. It was played every year, taking turns between the capitals of both countries, Accra and Lagos.

1951 saw the first edition play out in Lagos. The Nigerians sent the Gold Coast packing with five goals to nothing.

After a no-show in 1952, the Cup made a return in Accra for the 1953 edition, the first international game at the Accra stadium, built and opened the year before. The great CK Gyamfi scored the only goal as the Gold Coast avenged ’51 and claimed their first trophy.

In 1954, the Gold Coast XI travelled to Lagos.

Lagos? Same old story. Three goals to nil. Of course, against the Gold Coast XI.

Ahhh, so this was how things were playing out, huh? Each country making their home a fortress?

Okay. 1955 in Accra was a date then.

So yes, back to October 29. At the back pages of the Daily Graphic, the sports section was a serious scene of Gold Coast versus Nigeria analysis. Kofi Badu, the finest sports writer of the 50s, was in the thick of affairs.

“We want more of this devastation stuff from Gyamfi!” Badu wrote.

Beneath this plea was a photo of Nigerian keeper Carl O’dywer, lying face down on the pitch, with the ball, which had just left the “magic feet” of CK Gyamfi, headed to the net.

It was a timely still picture from the only goal that won the Gold Coast the Jalco Cup in ’53, its first ever trophy.

Badu and co covered it all: Who was playing? Who was winning? And by how many goals? What were the stakeholders saying? It was all happening.

The only thing that was missed — and perhaps it was so because no one knew it would be the beginning of a story of greatness — was the fact that a tall, lanky prodigy from Kumasi called Baba Yara was set to make his national debut.

So, just out of curiosity, what else was in that day’s paper for anyone not interested in sports.

Anything of note?

Well, yes.

There was actually a whole supplement in the paper. And its front page was a warning:

“WAKE UP!” the headline yelled. “THERE IS DEATH ON OUR ROADS! YOUR LIFE IS IN DANGER!”

Then, beneath this, these words:

Don’t overspeed. Don’t be careless. Be responsible.

Aw, Kwame Siaw!

Sunday, October 30, 1955 — A Star is born

This was it. The D-day. Jalco Cup 1955. Make or break. Raw war.

You know what? No need to write much here. Let’s cut to the chase.

So?

So, two words: seven zero.

Seven. Zero.

Again, 7–0. Against Nigeria.

Seven as in N-I-G-E-R-I-A.

The Gold Coast XI was in obscene form. Merciless. Matchless.

And guess who announced himself on the big stage with a classic debut performance? Even capping it with two goals and two assists?

Osman Seidu Maada — 19-year-old Baba Yara.

Instant hero.

February 20, 1960 — The prophecy

The Daily Graphic was sure. They had decided.

“Our choice!” they announced on their front page. “The Graphic has chosen Baba Yara as Sportsman of the Year!”

Accompanying the headline was a photo of Baba Yara in his elements for Ghana, seemingly running down the right wing, looking to send in a signature crisp cross.

Baba Yara, soon to become the captain of the Black Stars, was the third footballer to receive the coveted Sportsman of the Year trophy, after former national captains C.K Gyamfi in 1953, and E.C Briandt in 1955.

He had performed well in the year (’59) under review, scoring 7 goals and winning the Jalco Cup for Ghana, and the league title with Kotoko.

In his eulogy to Yara, Graphic Sports editor J.K Addo Twum wrote that Yara was a “born footballer”, with “extraordinary skill and dribbling wizardry”.

But perhaps Addo Twum’s most significant words came at the end of the article.

“In offering our congratulations to this great footballer, we only hope that injury will not interfere with his career, which seems destined to take him right to the top.”

Wow.

It’s as if Addo Twum knew.

The Man!

As a man, Baba Yara was almost angelic.

He was charisma in the flesh, beloved and held in high esteem.

Alex Ayim Ohene, author of “The Glory Days: The soccer legends of Ghana’s Gold Coast”, wrote that Yara was “a hero to most, a superman to many, and a saint to some”.

“To me,” Ohene continued, “he was an angel. I love his glowing prettiness, I loved his charm, I loved his manners and style, and I admired the great dignity with which he carried himself to the end.”

Ohene went on to call Yara a “rarity”, praising his “ebullient personality and cheeky good looks”, which made sure his popularity was “well ahead of his rivals.”

Yara was “gregarious, helpful, generous and caring” according to Pare.

He was “shy looking and respectable” according to JK Addo Twum.

The Ghanaian Times said Yara “was not only a great footballer, but a gentleman,” adding, “he was quiet, affable, unassuming, and always smiling.”

According to Charles Asante, Baba Yara’s life was “pure and gentle”.

“He was a fair gentleman with a handsome build and a welcoming smile,” he wrote. “He was a friend to all, young and old, tops and commoners. Wherever he went, fans pointed at him and said: “this is the man!”

Yara, according to an editorial by the Ghanaian Times, was booked only once in his career.

For the Black Stars, he was punished only once too. This was early in 1963, on the eve of the third edition of the Nkrumah Gold Cup, when Black Stars coach CK Gyamfi, a stern disciplinarian, sacked Yara from camp after he claimed Yara attended a dance at a night club without his permission

(Note: It is not known if this was at La Ronde night club, where Yara won the “best dressed gentleman” competition as recounted earlier)

The well-behaved Yara respectfully claimed that he had indeed taken permission (perhaps not from Gyamfi himself). True to form, Yara was almost immediately recalled, and he would go on to score in both the semi-final and final to help Ghana win that tournament.

“His personality was straight from God,” Dogo Moro swears.

Moro is right.

Yara’s versatility was unique and awe-inspiring, according to those who knew him. He was like a polymath. Intelligent to a fault. He could do a variety of things, almost everything. In fact, rumours had it that he could even pilot a plane!

Hearts chairman H.P Nyemetei called him “Ghana’s sports celebrity.” “His conduct on and off the pitch was an example of remarkable sportsmanship,” he said. “Until his last breath, Yara’s image lingered in the minds of the sports public of the country, and would continue to linger for all times. Nothing can be more monumental than this.”

The National League Clubs Association said Yara’s “sportsmanlike attributes and modesty both on the field and outside of it” was “a shining example and a guide to our present and future sports men.”

“Look,” said Ibrahim Sunday, a Kotoko legend and winner of the 1971 Africa Player of the Year award. “At that time, the president of France, he made a remark that in Ghana, we don’t know anything. All we know is ‘Baba Yara, Baba Yara!”

Sunday added, in an interview with FootballMadeInGhana: “You see, that means that even at a time when the media was not as developed as it is now, Yara’s name was even in France. If it were today, maybe we would compare him with Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi.”

When Ohene Djan wrote the book: “A brief history of soccer in Ghana and the rise of the Black Star Eleven” in 1964, he dedicated it wholly and “proudly” to Baba Yara.

(Fun fact: current Ghana president Nana Akufo-Addo, then a student at the University of Ghana, Legon, helped edit the manuscript of this book)

The book was the first ever piece of literature in Ghana football, according to the media.

“The desire to publish a book on Ghana football around this time dawned upon me rather intuitively as a means of paying tribute to Baba Yara, who was perhaps the most colourful footballer of the reformation era,” Djan wrote.

The Player

After announcing his terrific talent with a perfect performance in the 7–0 thrashing of Nigeria, at Jalco Cup ’55, Yara was poised for a bright future with the national team.

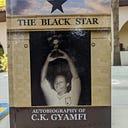

As CK Gyamfi wrote in his autobiography, “The Black Star”, Yara “served the national team for eight years, ever present, with no fuss nor ego issues. He was a star at the heart of the team’s rise, and success story. With the Black Stars, he embodied the beauty of national duty.”

Yara won the 1959 Jalco Cup, the 1959 and 1960 Nkrumah Gold Cup, the 1961 Azikiwe Cup, and the 1962 Uhuru Cup.

In August 1959, he became a foundation member of the Black Stars, and in November 1960, was named the team’s third captain.

As captain, Baba Yara would go on to lead the team through a successful tour of Eastern Europe, where they won eight out of 12 matches.

In 1961, he would almost lead the Black Stars to the World Cup.

The team drew a first leg second round qualifier against Morocco at home, and narrowly lost the second leg by a goal to nil. It is believed that Yara, who got injured ahead of the second leg, was the reason why the team lost away in Casablanca.

After sportingly surrendering the captaincy back to its former occupant, Edward Aggrey Fynn, Baba Yara had had a proud record as leader. “The authorities could not have made a better choice,” a fan wrote. “There is nobody to dispute the fact that Baba Yara is a disciplined player.”

His last act for the Black Stars came on March 3, 1963 — when in the 37th minute of the Black Stars’ Nkrumah Gold Cup final against Mali, he struck a 40-yard shot which ended up in the net to give Ghana a two-goal lead.

The match would end four nil, and Ghana would lift their third Nkrumah Gold Cup trophy. It was believed that this was Yara’s 51st goal on his 49th cap for Ghana.

Nine months later, the Black Stars would win their first Africa Cup title, with Baba Yara conspicuosly missing. “Our finest star was missing at our finest hour,” CK Gyamfi wrote.

After winning the Africa Cup, the entire Black Stars team went to Yara’s home at Kanda Estate and showed him the Abdelaziz Abdellah Salem trophy.

Baba Yara lay in his bed as captain Edward Aggrey Fynn presented him the trophy.

He smiled.

At club level, Yara was equally as influential. He captained Kotoko to the 1959 league title and the 1960 FA Cup. As a youngster, he also scored in the 1958 FA Cup final — the very first Ghana FA Cup final — in a famous 4–2 win over Hearts of Oak.

With Republikans, Yara won three FA Cup titles and the 1963 league title, even though he didn’t make it to the end of that season.

Yara was ridiculously beloved as a baller across the country. That he was popular was an understatement.

Need evidence of this?

Well, here’s a story: there was one-time Republikans were going to play Kotoko. It was the first time the two clubs were meeting after Yara and Moro had been plucked from the Porcupine Warriors.

The story goes that irate Kotoko fans warned Yara not to come to Kumasi, threatening to beat him up. Ohene Djan advised Yara not to go. Even Dogo Moro did not go.

But brave Yara went, and Republikans eventually won, with Yara putting in a man of the match performance.

During the match, the embittered Kotoko fans couldn’t help but be seduced by their prodigal son. “Yara ooo Yara!” they would praise anytime their star opponent would maraud down the right wing.

In games between Ghana’s two biggest teams and sworn enemies, Asante Kotoko and Hearts of Oak, Baba Yara was a regular scorer and show-runner.

Sources claim that he scored 8 goals in such matches, called the “Super Clash”, Ghana’s version of the El Classico.

Ohene Djan called Baba Yara a “natural footballer”. “He believed that a coach’s primary duty, like the music master, was to teach the student to read the notes and that the student’s own ingenuity and creativity should enable him to make melodious music,” he wrote.

“He was a total footballer,” says Osei Kofi, winner of the 1965 Africa Cup with Ghana. “I was handicapped with height, but he had it all — height, size, knowledge, technique. When it came to individual brilliance, teamwork and assisting, he was almost spotless.”

Dogo Moro: “He knew dribbling, shooting, passing — everything. He had speed, too. If you saw him control a ball with his chest, you’d marvel!”

“He was special,” Moro continues. “If you saw him approaching, you’d immediately know he was a good footballer, even before he touched the ball. He was so good he used to even advice George Ainsley, our first national coach.”

Addo Twum: “His immaculate ball control and magnificent body swerves usually sent fans into dreamland. His intelligence was beyond description. He was in a class of his own as a schemer.”

CK Gyamfi, who played with and coached Yara, said Yara’s feet “governed the ball with gilt-edged grace.” Gyamfi added that Yara was the greatest Ghanaian footballer he ever saw.

This perhaps is the highest praise there is, because Gyamfi, without doubt the most influential personality in Ghana’s football history, saw many generations of players, from the the 40s to the 2010s — close to 70 years .

Wilberforce Mfum: “Yara could juggle the ball a hundred times with both feet, and perform feats with the ball which were unreal. He was a player!”

Ken Bediako compares Yara’s style to Cristiano Ronaldo — both wingers, both dribblers, both goal scorers. “He was a dribbler and a goal scorer, just like Ronaldo,” he says.

Alex Ayim Ohene wrote that Baba Yara’s dribbling skills were “never likely to be equalled”. Yara could “read the game as well as he played it”, Ohene continued, “and watching him was like watching a musical virtuoso performing Mozart’s Magic Flute”.

“I can’t think of anybody new who can compare to Baba Yara. He was in a class of his own,” says Joe “Over to You” Lartey, Ghana’s legendary commentator. “I would say he was a maestro.”

“He was an artist,” wrote Charles Asante. “His bodily flexibility was one of his most outstanding qualities.”

Asante added that Yara had an “unselfish attitude during play”.

H.P Nyemetei called Yara a “specimen footballer”. “He was great,” he added.

Nigerian FA President then, Godfrey Amachree, called Yara “Africa’s greatest soccer star” and “the kingpin of Ghanaian soccer”. “He was the bête noire of the Nigerian team,” he said. “No strategy employed against him could stop him.”

“He did not allow his brilliance on the field of play to make him forget that soccer is teamwork,” Amachree added. “This unselfish trait, coupled with his dedication to the sport, is what set him apart.”

The Ghanaian Times said Yara was “one of the greatest Africans to don a jersey and lace on a leather boot.”

In reporting his funeral, the Times revised the above, simply calling Yara “Ghana’s greatest player”.

“He made Sundays one of the most enjoyable moments for the soccer fan,” they added. “He thrilled fans in Ghana, on the continent of Africa, and in Europe with his immaculate soccer prowess and his uncanny ability to get goals from almost impossible angles.”

Speaking of impossible angles, Joe Lartey remembers Yara being a master of corner kicks. He had this way of bending the ball such that it would go all the way to land on the cross bar. “Sometimes, it even went in!” Lartey claims with nostalgia

Baba Yara’s monikers were many:

“King of Wingers”;

“King of Right Wingers”;

“King of West African Wingers”;

— or the most powerful one,

“The Stanley Matthews of Africa.”

His fame spread across Ghana, transcended West Africa, and rang loud across the continent.

It is claimed by Kofi Pare that once, an unnamed African Head of State was asked what he knew about Ghana.

“Ghana. Baba Yara. Football.” he simply said.

Yara was named Footballer of the Year twice, and in 1961, was named “The most distinguished member of the Black Star Group” — the highest state honour for footballers — right after being named Sportsman of the Year.

“Here was a football genius,” Ohene Djan wrote. “When cometh another?”

May 5, 1969 — The call: Part II

After Graphic Sports editor Addo Twum spoke to Yara’s brother at Yara’s Kanda home, he was still steeped in shock, destabilized with disbelief.

Apparently, according to Yara’s brother, Yara had been admitted at the Korle Bu hospital in critical condition, and had died shortly afterwards.

Addo Twum was particularly fond of Yara, not only because he was an excellent footballer, but because of something else that told of the humanity of Yara.

“My association with Yara was more than that,” he would later write. “But for Yara, Dogo Moro and (Mohammed) Salisu, I should not have been in the world today.

The story: “In 1954, when I was covering a football match between Kotoko and Hearts at the Kumasi Jackson’s Park, I was attacked by a mob, and my saviours were these three gentlemen. I will never forget Yara.”

At Baba Yara’s funeral, there was wailing and weeping among present and past footballers, sports personalities, administrators, relatives, fans — and just about everyone who had heard of the iconic name.

According to the Daily Graphic, thousands of men and women came to pay their last respect, even on short notice. The Ghanaian Times wrote that the funeral “could easily pass for the most touching for any sports personality in the country”.

There was a long procession to the Accra Stadium, led by some foundation members of the Black Stars, who carried his “well decorated”, Kente draped coffin.

Edward Acquah, in particular, cried like a baby as he walked beside the coffin.

The mourners then proceeded to the Odorkor cemetery, where the King of Wingers, Ghana football’s crown jewel, was laid to rest.

Over in Kumasi, Yara’s adopted home, the mood was grim. Across drinking bars, restaurants, various offices and street corners, the topic of discussion was singular: Baba Yara.

Kwamena Longdon was a reporter for the Ghanaian Times who decided to go around town to see how people were receiving the news.

He reported: “I saw various groups of grief-stricken people discussing and recalling the invaluable and priceless services that the ‘King of Right Wingers’ rendered not only to Kotoko, but to the general progress of football in Ghana.”

Even Kotoko, who had had a gripe with Yara for leaving them, paid glowing tributes.

J. Oppong Agyare, the General Secretary of Kotoko, said Yara will be “remembered as long as football is played in Ghana.”

“The nation has been robbed!”

Baba Yara’s career-ending injuring occurred when he was 27, and his premature demise at the young age of 33.

“I would say his life was truncated,” Joe Lartey told Saddick Adams. “Cut short.”

“A wave of shock ran through almost every home,” The Ghanaian Times said.

Kotoko Executive Director B.K Edusei said Yara’s career had been “suddenly extinguished” by the Kpeve accident and spinal injury.

The day after his death and burial, the press seemed dumbfounded, with abrupt headlines.

“Baba Yara is dead” the Times simply announced.

“Soccer King Yara is dead” said the Daily Graphic.

But the tributes were many, colourful, heartfelt and profound.

JK Addo Twum wrote a tribute titled “The end of a great star”.

“He was a born sportsman who died for sports,” he wrote. “Though dead, his spectacular exploits on the soccer field will long be remembered.”

Nigerian FA chief Godfrey Amachree said: “If ever there should be a hall of fame of Africa’s great sportsmen, Baba Yara’s name will be inscribed on the roll of honour.”

The National League Clubs Association called Yara “a genius and a rare pearl.”

“No words of praise can adequately compensate this nation for the loss,” they added, going on to say that Yara, as a footballer, was “the best produced so far in this Western part of Africa.”

B.K Edusei said he admired Yara for “the beauty of his style of play, his sobriety, his respect for authority, his love for sports as an art and his love for his country”.

“The nation has been robbed!” read a headline from the Ghanaian Times.

The Times’ editorial said that it was an “irony of fate that the very sport which brought him from obscurity into national prominence was to be instrumental in his incapacitation and eventual death.”

It was announced that not one, but two minutes of silence would be observed at all matches at colts level to honour the memory of Baba Yara, who loved and excelled at colts level, the grassroots of Ghana football.

In all, Yara had spent six years, one month, one week and three days bed-ridden.

The Ghanaian Times described his years living with paralysis as “pain-enduring”.

Yara and those who cared about him had tried everything to get him to walk again.

There was the UK trip to the Stoke Mandeville hospital, and there was the native, religious means.

In November 1963, Prophet Daniel Nubah, a Kumasi-based spiritual healer, offered to help heal Yara.

Nubah, founder of the Ghana Holy Healing Church, claimed he could get Yara on his feet in no time. Within three months of treatment, to be exact. He sent a delegation to Yara’s home in Kanda to discuss his offer.

Yara accepted the offer. Of course, he desperately wanted to walk again. But his only problem, as his wife Patience said, was that Yara was not “in a very good position to travel” to Kumasi.

“We are very anxious to get Yara treated and if we don’t succeed in bringing down the healer to Accra, we shall be compelled to go to Kumasi,” Patience said.

It is unknown if Yara went to Kumasi, or if Nubah came to Accra, or even if the treatment ever happened, but we do know that Yara still remained in a wheel chair for six more years.

B.K Edusei, who was a man confined to a wheelchair himself, said Yara had displayed “stupendous courage” in managing “the burden of his illness and the pain of inactivity.”

Yara had had a “quiet dignity” in facing “the utter hopelessness of the future” according to the respected and wealthy Edusei.

All the way through, in bed and in a wheelchair, Yara remained hopeful and grateful.

“I am very pleased that though I am inactive on the sporting field, I have people and groups and associations in the country who think of me,” he once said.

It is said, according to an account from Alex Ayim Ohene, that on Baba Yara’s death bed, shortly before he took his last breath, his loving wife, Patience, took hold of his hand and “squeezed it gently, as if to say ‘I love you’.”

Ohene: “Baba Yara smiled, looked at her, and just said: ‘as my days rapidly draw to a close, I am proud to be counted among those who contributed to what was best in our noble game’.”

B.K Edusei, in wrapping up his tribute to Yara, said he imagined these were Yara’s last words:

“Whatever you have to do, do it well.

If misfortune befalls you, be brave.

In all things, do not mumble or complain.

But always trust in the power and wisdom of the Almighty,”

Indeed.

Yara did what he did well.

He was brave in misfortune.

He never mumbled nor complained.

And, above all, he trusted in the power and wisdom of the Almighty, right till the very end.

Baba Yara, ladies and gentlemen.